Saville and Douglas - Theatre and Legerdemain

Destitute in Bathurst

Letter (1) to the Colonial Secretary, dated at Bathurst January 18, 1844:

Sir,

I have the honor to request that a license may be granted to me for fourteen nights of Theatrical performances, to be held in a building erected as a Theatre, on the premises of James Howard Coach & Horses Inn, Kelso, being for the purpose of enabling myself and six others to quit this town.

I beg to inform you that we lately performed under the license granted to Mr. Wm Henry Douglas, and which terminated on the 30th November, since which period we have been endeavouring to procure other employment, but without the slightest prospect of success, and are consequently placed in very destitute circumstances.

I beg to stage that I have waited twice on the Police Magistrate for his recommendation, but he withheld it in consequence of having on a former occasion opposed the application of Mr. Douglas.

I therefore most respectfully request that your Honor will be please to take our situation into your serious consideration and by granting our request thereby enable us to quit a Town where we have no longer any hope of obtaining a livelihood.

I have the honor to be, Sir,

Your most obedient humble Servt.

Charles Faucit Saville

The Colonial Secretary’s response to this request was

“I regret that I cannot comply with the request.” 22 Jany.

Licensing Applications to the Colonial Secretary

This story contains very little relating to conjuring; in fact its slender connection with the topic rests on a couple of brief references to “Legerdemain”; however the tale is a good example of the problems experienced by performers in the early to mid 1800s, and pulls together some interesting theatrical threads.

From September 1828 until October 1850, the Colony of New South Wales (which in the early 1800s encompassed almost all of Eastern Australia) imposed “An Act for Regulating Place of Public Exhibition and Entertainment”, under which the populace would be protected from the “evil consequences which the unrestricted power of opening places of public exhibition and entertainment in the present circumstances of this Colony must necessarily produce.” [For further detail on this Act, see Reference (2) ]

In effect, all presenters of public entertainments, whether on a stage, or in any public lecture hall, tavern, circus etc. were required to be licensed under penalty of a fine or six months’ gaol. Although, in 1850, the regulation was relaxed somewhat, requiring only entertainments “of the stage” to be licensed, the result for entertainers was a constant need to apply for permission to perform.

Not only would a solitary entertainer have to apply to the Colonial Secretary, they first needed to obtain the approval of the local region’s Police Magistrate, or Bench of Magistrates. The hurdles of convincing all parties firstly of one’s own good reputation, then the desirability of the entertainment and the respectability of the performance venue, must have made it very difficult indeed, even when a performer was fortunate enough to obtain a general license extending over several months; and problematic to obtain the same in time to advertise the season. In the case of magician Mons. Du Pree [Thomas Amott] his application was once delayed because the Police Magistrate had been away chasing bushrangers.

Messrs. Saville and Douglas, though they must have been devastated by the Secretary’s refusal to grant them a further license, seem to have managed to escape the grasp of Bathurst. On a number of further occasions, Charles Faucit Saville wrote again to the Colonial Secretary, seeking approval to produce entertainments, with mixed success.

Commenting on Saville’s application of February 26, 1844, to hold ‘Theatrical Representations’ at the Cricketer’s arm in Windsor, NSW over the course of three weeks, the Secretary noted, “ He must state more specifically the nature of the Theatrical representations he is desirous of giving.”

Saville followed up on March 1, writing (3) “Sir, In reply to the answer I had the honor of receiving from you this morning relative to my application for a license to hold Theatrical Representations in the town of Windsor, I beg to request that the said license may be issued in my name for holding Theatrical Representations, including Gymnastic and Acrobatic Exercises and feats of Legerdemain in the long room known by the sign of the “Cricketer’s Arms” kept by Mr. John Frederick Gillham, and the license to be in force for the period of Twenty one days.”

Accompanied by an annotation from the local Police Magistrate, this letter was successful in obtaining a license, and during March the Windsor Express advertised Mr. Saville’s performance at the “Royal Albert Theatre” with the ‘celebrated Dandie Dinmont Address’, the ‘romantic Drama of the Bandit Host’, and finally a “great variety of new and select Entertainments, got up expressly for this occasion” before concluding with the farce of the ‘Rear Admiral’. Reviewing this production, the Windsor Express remarked, “at the neat little Theatre lately established in Windsor … a decided hit … we cannot expect to find a ‘theatre’ in Windsor equal to that of the Metropolis, but it is possible to find Performers, oftentimes equal, if not superior, to those whose names swell public Chronicles in other places.” (4)

Later applications (5) in May and August 1844 were rejected by the Colonial Secretary, although the requests were phrased in the same terms, Theatrical Representation including Gymnastic and Acrobatic Exercises and feats of Legerdemain. In these cases Saville had placed reliance on a previous consent from the Police Magistrate, or failed to provide the PM’s consent, and the Colonial Secretary refused to sign off without proper local approval.

So far as any connection to the performance of legerdemain is concerned, we have no further details. Having awoken our interest in Mr. Saville and Mr. Douglas, however, we have been tempted into digging at least a little more deeply into their theatrical history.

William Henry Douglas

William Douglas (6) was applying to the Colonial Secretary for performance licenses as early as 1842, barely ten years after the earliest theatres were established in the main population centre, Sydney.

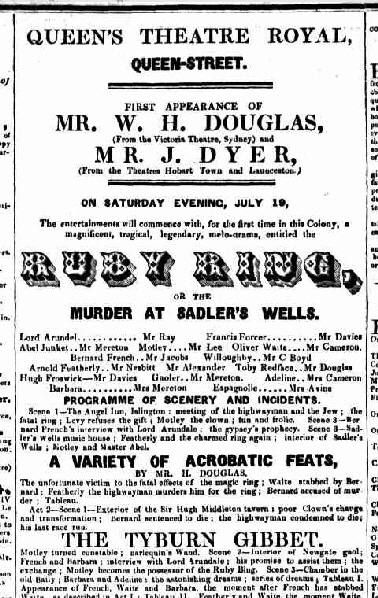

Douglas at Queens Theatre 1845 Jul 19

In January 1843 he is noted (7) as the Manager of the Goulburn Theatre, south-west of Sydney. where he presented Mr. Holland’s Fantoccini (puppets) and also his own “extraordinary feats of flexibility, also the various feats of Gymnasium, on the horizontal bars”; clearly the skills which Saville and Douglas would exhibit later.

After some period of being in connection with Mr. Saville, and surviving his ‘destitution’ in Bathurst, the pair appear to have gone their own ways, and Douglas was seen, albeit briefly, as an actor at Sydney’s Victoria Theatre in October 1844 (8). He then appeared at the Queen’s Theatre in Melbourne (9) on July 19, 1845, again showing off his acrobatic skills as part of a melodrama titled “Ruby Ring, or the Murder at Sadler’s Wells”. In July 1846 he was a witness in a minor court case in Melbourne, in which newspaper reports (10) mention him as being a former manager of a Sydney theatrical troupe. 1853 sees W.H.Douglas back living at his old stomping ground, Bathurst, as the Manager of the Bathurst Theatre “near Whittle’s Coal Depot”.

And, without attempting to document his entire career, he must have had some success, for in October 1877, he performed with the Sydney Theatre Royal dramatic company at the Academy of Music in Ballarat, Victoria, in support of the famed actress Mrs Scott-Siddons (11). Said the Ballarat Star (12), “Mr Douglas played Count Tristan, the lover, in a manly way …. in the second piece … Captain Rolando, the misogynist … was excellently given by Mr W.H.Douglas.”

Charles Faucit Saville

Mr. Saville proves to have a theatrical family heritage of considerable prestige, though his Australian career may not have started well.

Helen Faucit

He was born September 16, 1816, the son of actor and playwright John Saville Faucit (13), and the brother of the most famous family member, (14) Helen (later Helena) Faucit. Helen made her London acting debut in 1836 and was an immediate success, and became a celebrity performer in roles such as Lady Macbeth and Juliet until, in 1851 she married Theodore Martin, and later became Lady Martin, still acting for charitable causes. She died in 1892.

Charles arrived in Sydney around August 1838 and, on September 8, was advertised “From the Theatre Royal, London, for this night only” and “of well-known celebrity on the London boards, will appear before the Australian Public for the first time”, in the character of Octavian in Coleman’s admired play of the ‘Mountaineers’.

If however, his reflected glory was expected to ensure his success, Charles was to be sadly disappointed.

(15) [Sydney Gazette] - “The Victoria Theatre. A new performer, a Mr. Charles Faucit, made his first appearance before an Australian audience, in the character of Octavian, in The Mountaineers, for Grove's benefit, on Saturday night. Mr. Faucit was very favourably received by the audience but his appearance gave the lie direct to the announcement in the bill, that he had just come from the Theatre Royal, London. We cannot sufficiently condemn the practice, which has ever been too prevalent here, of announcing new performers on their first appearance as from the Theatres Royal, London, unless there be really some foundation for the intimation. The very effect of the announcement is to raise a prejudice against the debutant in the minds of some, and in all to excite a degree of expectation which, if not realized, operates most injuriously against the new performer. To have announced Mr. Faucit, in less sounding terms, would not have rendered his failure in Octavian less palpable, but it would have made his auditory more disposed to deal leniently with his faults, and might have saved him the galling remarks which followed the fall of the curtain. In person and appearance Mr. Faucit is well enough, and his voice, allowing for a little of the trepidation natural on a first appearance, is by no means amiss ; his reading is remarkably correct, and undisfigured by those vulgar cockneyisms which no correction will amend in Lazar, Simmons, Arabin. &c. There, however, our commendation must stop. His declamation resembles the sing-song elocution of a school-boy, his gesticulation is nearly as bad as Fenton's, and he seems as firmly rooted to the portion of the stage where he first takes up his stand as if some kind friend had nailed him there. In conclusion, Mr. Faucit is not deficient in theatrical ability, and with a little attention, taking Collin's for his foil, he may one day make a very tolerable performer.”

Perhaps this inspired Charles Faucit Saville to work hard at his craft, and to pay his dues in the regional areas of the state; by 1845 he was back at the Victoria Theatre again and, happily, at many other theatres for years to come. His family connections continued to raise expectations which he must have been hard-pressed to live up to - for a season of “A Wife’s Revenge” at the Royal Olympic Theatre Launceston, the advertising listed every acting member of his family, proclaiming Charles as the brother of the great tragic actress and saying that any eulogy on upon the members of this talented family would be superfluous to the patrons of the drama. No pressure there…

Charles Faucit Saville continued for many more years to be seen on the Australian stage, and again, without attempting to document his entire career, a “Mr. Saville” appears in many theatrical productions in Australia well into the late 1850s.

REFERENCES

(1) Application letter held on microfilm reel 2259, State Records NSW: Colonial Secretary; NRS 905, Main series of letters received, Ref. 44/519.

(2) Refer to my notes on Sources under “State Records NSW”. Archivist Janette Pelosi’s writings on the Colonial Secretary’s licensing powers is documented in several essays, including “Submitted for Approval of the Colonial Secretary”, published in “A World of Popular Entertainments” [Ed. Gillian Arrighi and Victor Emeljanow, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2012.]

(3) Letter held on microfilm reel 2259, State Records NSW: Colonial Secretary; NRS 905, Main series of letters received, Ref. 44/1666.

(4) Windsor Express and Richmond Advertiser, March 28, 1844

(5) Letters held on microfilm reel 2259, State Records NSW: Colonial Secretary; NRS 905, Main series of letters received, 44/4112 – 25th May 1844 for ‘approval to perform in a building erected for that purpose, belonging to Mr. Frederick Morgan and adjoining the premises of [Mrs. Mary] Black situated in Durham Street Bathurst and the said license to be in force for the period of six calendar months.’

And reel 2259, State Records NSW: Colonial Secretary; NRS 905, Main series of letters received, 44/6614 “for holding Theatrical Representations including Legerdemain, Gymnastics and Acrobatic exercises etc. in a building at the rear of the house known by the sign of the “White Heart Inn” kept by Mr Walter Blanchard, and situated in George Street Windsor; and the said license to be in force for the period of one calendar month.”

(6) The most productive online search for Douglas is to search for “W. H. Douglas”

(7) Sydney Morning Herald, January 30, 1843 page 3.

(8) Sydney Morning Herald, October 30, 1844 page 2

(9) Port Phillip Gazette July 19, 1845 page 3

(10) Port Phillip Patriot and Morning Advertiser July 22, 1846 page 2.

(11) Mrs. Scott Siddons https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_Frances_Scott-Siddons

(12) Ballarat Star, October 9, 1877 page 3

(13) The names ‘Faucit Saville’ are frequently reversed to ‘Saville Faucit’. To add to the difficulties for the humble researcher, the names are also sometimes spelled as Savill or Fawcett, and the actors appeared on stage under such titles as “Mr. Faucit” or “Mr. Saville”.

(14) Helen Faucit: Fire and Ice on the Victorian Stage, by Carol Jones Carlisle. London, Society for Theatre Research, 2000

(15) Review in the Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, September 11, 1838