Alfred Silvester – the Fakir of Oolu and his Family of Magic

Chapter Ten – Alfred Silvester Silvester [continued]

“It is unnecessary to say that the name of Silvester is a household word. For years past the ‘Fakir of Oolu’ has graced the footlights and entertained the public. The mystery enshrouding his performance has always been a source of pleasure and relief, and his appearance here, we are sure, will be heartily welcomed.”

– Port Pirie Standard, February 1, 1894

– Port Pirie Standard, February 1, 1894

Having departed Western Australia in February 1889, Alfred headed back to familiar territory in Melbourne, but however he was making a living it was not on the stage. Almost nothing can be unearthed about his activities during the rest of the year, save for a single appearance on July 13 at a “People’s Concert” in the Russell Street Temperance Hall. For the first time, Alfred was described as The Fakir of Oolu, although this would never more than an occasional billing.

In 1890 Alfred launched back into performing, and it seems that his greater successes always came when he joined forces with another performer, perhaps one with a better business sense or organisational ability. Several new names are involved in the next phase, so we will firstly draw those threads together. While it might be easier to cut to the chase and speak only of Silvester, there are so many other magic-related connections that the diversion should prove worthwhile.

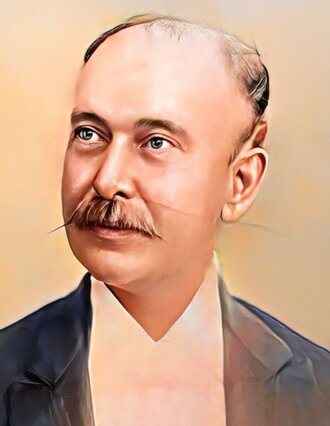

A. Litherland Cunard

A. Litherland CunardIn Chapter Five it was related that the up-and-coming American illusionist, Harry Keller (later Kellar), along with his partner William Marion Fay, lost everything in a shipwreck in 1875. Fay decided to give away performing, but Keller managed to borrow some money to re-fit his show.

He then took on another partner as his assistant in the Davenport Séance routine, a Britisher from a printing background, rejoicing in the name Archimedes Socrates Cicero Litherland (1844-1905) to which he later appended the professional name ‘Cunard’. He travelled extensively with Keller’s “Royal Illusionists” until mid-1876 before leaving the company, and his title was then adopted by another performer, David Hayman, who worked as ‘Cunard’ during Kellar’s Australian tour in late 1876.

After possibly returning to Britain and managing a circus at the Southport Wintergarden, he appears to have rejoined forces with Kellar. Caution is needed since others had also used the stage name Cunard (1), but when Kellar reached Australia in May 1882, his business manager was Mr. A. Litherland. In 1883, Cunard was the manager to sharp-shooter Colonel Ike Austin, offering himself up as the brave assistant whose cigar was shot from his mouth by the Colonel. In 1885 he was the acting manager of the Gaiety Theatre, for proprietor John Solomon.

Litherland/Cunard settled in Australia and married the singer Helen Gordon. He would be known principally as a theatrical manager, but also as a purveyor of illusions.

John Solomon

Solomon is a significant Sydney theatrical entrepreneur, though his activities are not well documented. By trade an auctioneer in George Street, (2), he was the promoter of various spectacles such as a baby beauty pageant, and a proposed visit from the Buffalo Bill Wild West Show in 1889. He was at times the proprietor of the Coogee Palace Aquarium, the Gaiety Theatre in Pitt Street, and an interesting exhibition with Afghan magicians at the “Egyptian Hall and Palace of Mystery” during 1880, which will be documented in a separate essay. Solomon’s major claim to fame was to have funded the design and construction of the Criterion Theatre on Park Street which would become the spiritual home of Sydney theatrical performers for decades to come – when, in 1935, the theatre had to be demolished to make way for the widening of Park Street, it was replaced by the (still existing) Criterion Hotel, and the corner of that intersection was known as “Poverty Point”, a gathering place for performers seeking work.

Wax Works Exhibitions

The extensive story of waxwork displays in Australia revolves largely around the two most significant players, Max Kreitmayer whose most famous establishment was in Melbourne (3), and Madame Sohier (Ellen Williams) who likewise operated in Melbourne but established a Sydney wax works at 220 Pitt Street, (which became the Wesley Centre and Lyceum Theatre) and then at 267 Pitt Street. The date when the Pitt Street venue closed is a little uncertain and, in fact, Madame Sohier’s waxworks undertook an extensive tour of New South Wales during the 1890s. There were also a number of other short and longer-term waxworks in Sydney.For our purposes we are interested in Kreitmayer’s many other theatrical and magical exhibitions at his Melbourne establishment, and the creation of the “Australian Waxworks” by Edwin Eureka Sohier, son of the original waxworker, and a Mr. Richard Kretschmar.

Alfred Silvester and Archimedes Litherland Cunard

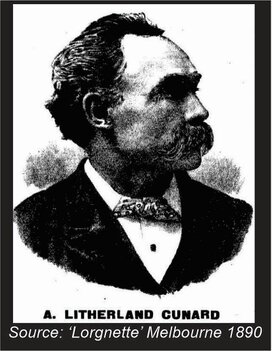

Mr. Cunard was, in 1889, busy in Melbourne with projects including a proposal to manage a new city Music Hall at the Palace Hotel, which appears to have foundered on the rental being asked. In December he introduced an illusion at Kreitmayer’s Waxworks, which regularly featured novel scientific and magical displays for their customers. The illusion was titled ‘Amphitrite’ and it was suggested to be Cunard’s invention; this is unlikely since the illusion was also being hailed as having been a great success at the Paris Exhibition. (4)

Some versions may have presented this illusion as an apparent levitation. In the Australian form, a young lady was seen to be floating, turning and diving peacefully inside a large tank filled with water. It was a clever optical illusion, made possible by our old favourite method, an angled pane of mirrored glass.

Amphitrite was amongst the same class of illusions as the 'Thauma' bodyless lady illusion; a fixed miniature stage or cabinet which could be set up as a static exhibition rather something performed by a magician as part of his stage show. Barnum’s 'American Museum' and the 'Eden Musee' were American examples of what would be termed ‘dime museums’ housing similar attractions.

In addition to Amphitrite, Cunard also featured 'Clio', an automaton which drew sketches. It had originated with Britain’s J.N. Maskelyne (as ‘Zoe’), was then copied by Harry Kellar as ‘Clio’, and continued by Cunard. Whether Cunard had acquired his automaton from Kellar, or had a copy made, is not known.

We can finally return to Alfred Silvester who, during 1889, made a connection with Cunard and formed plans to go with him to Sydney at the start of 1890. Matters here become unclear and we are forced to make some guesses about the situation, based on the chronology of events.

‘Amphitrite’ continued at the Waxworks until December 28, and the Herald said "It is by far the best illusion of its kind we have ever had in Melbourne, and is one that reflects the greatest credit on Mr. Cunard, its inventor." On December 30 the Herald announced that Amphitrite had been withdrawn “in favour of Kalypso, the new wonder to be seen today.”

To give the illusion its full title, ‘Kalypso and the Syrens’ was a development of ‘Amphitrite’ involving multiple swimming nymphs. Cunard and Silvester wished to depart from Kreitmayer’s and take Amphitrite to Sydney. The impression is that the Kreitmayer management created their own ‘improved Amphitrite’ to take its place, since the illusion was drawing good crowds.

In January, 1890, a civil lawsuit was filed in the Supreme Court of Victoria (5) naming both A. L. Cunard and A. Silvester as the plaintiffs, and Max Kreitmayer and his associates Herbert Winning and Thomas Holt as defendants. Their claim was “£500 in damages for the infringement of the plaintiff’s patent used in the production of certain scientific illusions styled by defendants ‘Kalypso and the Syrens’ and for an injunction to restrain the defendants from using the plaintiffs’ patent. And for an account of the moneys received by the Defendants or any or either of them by reason of the use by them of the plaintiffs’ patent.”

The ink on the patent mentioned must have still been drying, as the case was lodged on January 4, newspaper records show Provisional Patent 1950 having been registered on January 7, and the case set down for hearing on January 15. The description of the provisional protection names Cunard and Silvester “for improved apparatus for producing spectral illusions” and perhaps Alfred had used some of his family’s knowledge of the angled glass principle to suggest minor adjustments to the illusion, in order to justify the patent papers. It seems to have done them no good; Kalypso and her Syrens continued to swim happily at Kreitmayer’s for months to come, and the press reported the attraction as being very successful.

The Australian Waxworks and Solomon’s Museum

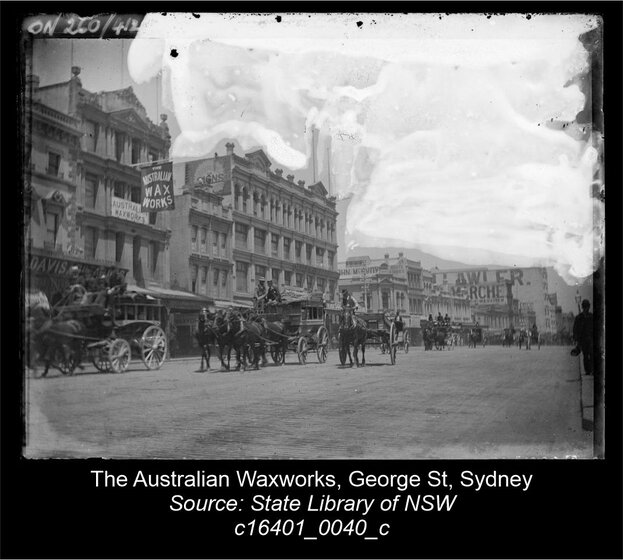

The Sydney destination for Silvester and Cunard was 'Solomon’s Royal Museum and Palace of Amusement', another venture of the entrepreneurial Mr. John Solomon. The Museum’s history fluctuates over the years – it began in December 1884 as ‘The Australian Waxworks’ located at 558 George Street in the heart of Sydney, directly opposite the Sydney Town Hall which was still undergoing the final stages of construction, and the longer-established St. Andrew’s Church.

The Waxworks was under a partnership between Maximilian Kreitmayer and the son of ‘Madame Sohier’, Edwin Eureka Sohier. Across three levels were displayed an array of religious, anthropological and political figures, with the mandatory Chamber of Horrors featuring grisly scenes of murder, bushranger corpses and dismembered bodies.

The Waxworks regularly featured other attractions, including a glass-blowing display, little Clara Cosbie (aged 12) explaining how she was lost in the bush and lived for three weeks without food, the 'Thauma' illusion and its variation 'Ihdas', and the Vanishing Lady (all advertised to be fully authorised by magician Hugh Simmons 'Doctor' Lynn). By 1886 they were exhibiting, a la Barnum, living giants and midgets.

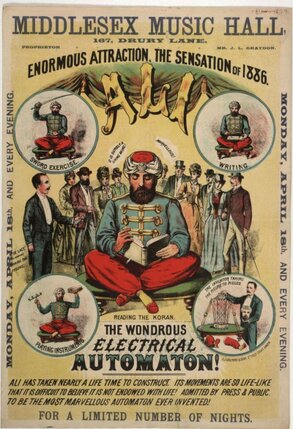

The partnership was dissolved in October 1887, leaving Edwin Sohier to carry on the business (apparently with the aid of a Mr. Kretschmar) but the business seems always to have been a successful and popular part of the entertainment scene. By March 1889, the star attraction was 'Ali, the Wonderful Electrical Automaton' ( who could perform sword exercises, play cards, take snuff, and play a tambourine or bells. Professor A. de Lacy was the inventor of this 'electrical automaton' which had been seen in Britain, and in Australia as early as August 1887 at Kreitmayer’s Melbourne Waxworks, and was able to undertake many movements and lifting functions before the operator ‘revealed’ the inner workings which, at least to appearances, was a mass of electrical apparatus.

'Jo-Jo the dog-headed boy' and 'Ubini’s Performing Fleas' arrived at the Wax Works in mid-1889 and by this date the Director’s name was advertised as Frank M. Clark.

'Jo-Jo the dog-headed boy' and 'Ubini’s Performing Fleas' arrived at the Wax Works in mid-1889 and by this date the Director’s name was advertised as Frank M. Clark.A curious confusion of ownership is seen over the next few months. Two new proprietors, Washburn and Roberts, were reported in July (6) to have refurbished the property and opened the 'Royal Museum and Palace of Amusement' while more-or-less retaining the same style of entertainments, including a number of Indian magicians. In September, however, the building was advertised for sale, and this advertising continued even after Mr. John Solomon stepped in as the operator. As Solomon had been advertising as early as August 1889 for “freaks of nature, curios, relics of all kinds” it is clear that the Waxworks’ change of operation had been coming for some time. Solomon was busy with fingers in many theatrical pies, including the lease of the York Street Opera House where Kellar had appeared, the Coogee Palace Aquarium, his proposed Wild West Show at Moore Park (which seems to have collapsed on the death of his business associate, Mr Allison), and the Gaiety Theatre in Pitt Street. He was also no stranger to the world of exhibiting 'curiosities', having operated the 'Egyptian Hall and Palace of Mystery' in George Street for a number of months during 1880.

Under Solomon’s control, the 'Royal Museum and Palace of Amusement', to become better known as 'Solomon’s Museum' was re-launched on October 19, 1889. The Sydney Morning Herald praised the refurbished handsome building and the array of new attractions, which included an electric orchestra, a man walking across spikes, a child sharp-shooter, an “electric lady” whose touch would shock people, a rapid sketch artist, and a continued display of both wax and mechanical figures. For the magical interest, “Flavia, the Corinthian Mystery” was another mirror-based illusion which turned a marble statue into a live figure and back again.

Professor Robert Jensen was also the resident magician; he had come to Australia in mid-June with his “Congress of Cabalistic Wonders”, dressed as an Indian prince and introducing new feats such as the “black art” act and the “talking skull” to the country. Though the Perth Inquirer said of him (7) “…. his séance of modern magic, the grace and ease with which he executed his various and most inexplicable feats, fairly won for him the hearts of the audience” he appears not to have met with the success he deserved. He had been at Melbourne’s Victoria Hall in August, with what the Melbourne Punch described as “a beggarly array of empty benches.” At Solomon’s he was displaying a Flying Carpet suspension illusion with his magic act.

Professor Robert Jensen was also the resident magician; he had come to Australia in mid-June with his “Congress of Cabalistic Wonders”, dressed as an Indian prince and introducing new feats such as the “black art” act and the “talking skull” to the country. Though the Perth Inquirer said of him (7) “…. his séance of modern magic, the grace and ease with which he executed his various and most inexplicable feats, fairly won for him the hearts of the audience” he appears not to have met with the success he deserved. He had been at Melbourne’s Victoria Hall in August, with what the Melbourne Punch described as “a beggarly array of empty benches.” At Solomon’s he was displaying a Flying Carpet suspension illusion with his magic act. As Jensen’s final week of performance began, Solomon advertised the arrival of Amphitrite the Water Nymph (“more lovely, more fascinating, more entrancing, and more gorgeous than any eye has hitherto beheld, a beautiful delicate creature of the deep”) on January 11, under the personal supervision of Cunard and Silvester. Following a preview on the 12th, the Daily Telegraph declared the illusion to be one of the best novelties now on the museum programme.

An interesting side-light is the brief appearance of the British magicians George Waldo Heller (Robert Wezner) and Maude Heller, not long arrived in Australia though they would tour here for decades to come.

Mr. Cunard was not just a magical performer at the museum. His role at Solomon’s was also that of General Manager, here and at Solomon’s Criterion Theatre. Alfred Silvester was engaged for his magical performances and, after Jensen departed, he introduced the Anoetos illusion (head on a swing) which his father had made such a feature in former years.

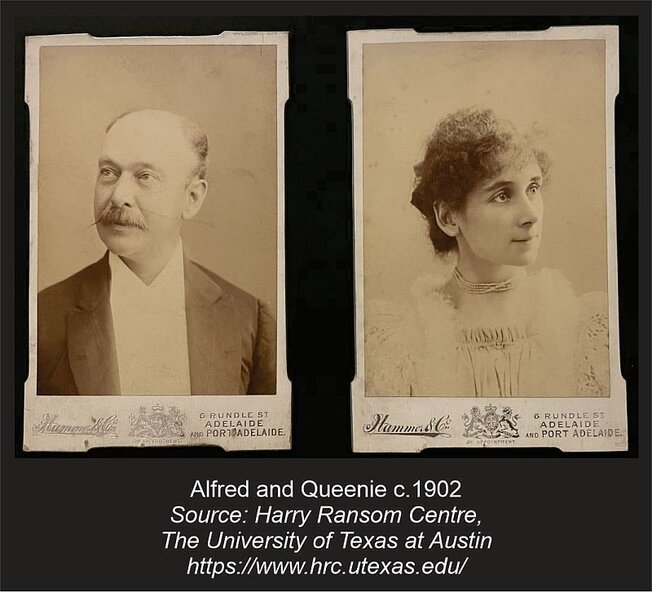

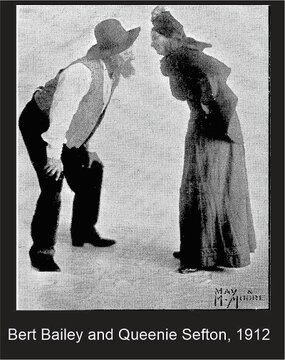

Queenie Sefton

All these magic creations required a female partner and assistant, and from the point of view of Alfred Silvester’s future life, Miss ‘Queenie’ Sefton was the most significant part of his time at Solomon’s Museum

In November 1889, a “Queenie Sefton” was listed as a member of the Melbourne waxworks (which also went by the name of “Royal Museum”) company for their twice-daily concert and variety entertainment. By February she was in Sydney performing the role of Amphitrite, the ‘beautiful delicate creature of the deep’ and when the Anoetos illusion was staged, Mr. Cunard was the Alchymist, Mr. Silvester gave the lecture, and “Miss T. Sefton” acted as the headsman. Despite the billing, it was as “Queenie Sefton” that she would later be named as ‘the other woman’ when, in 1891, Alfred’s abandoned wife Louisa was driven to finally sue for divorce. Previously, lacking the means to file a lawsuit, Louisa had remained Alfred’s formal wife, but now she felt it necessary to make a final break. The divorce, on the grounds of misconduct and desertion, was granted in June 1891, and Alfred did not appear in court.

Alfred Silvester and Queenie Sefton (some newspapers papers said “Annie Sefton” but this may have been a mistake; the divorce papers refer to ‘Queenie’), it was alleged, had committed multiple acts of adultery in Sydney, Adelaide and Melbourne. Was there an actual relationship between the two? The likelihood is fairly compelling, though not confirmed; but the pair were performing partners until 1904.

It is difficult to locate much personal information about ‘Queenie’ despite the fact that she would have a lengthy career with Alfred Silvester and, as it happens, an even more successful career on the stage after his death in 1907.

From a combination of sources (see more detail at reference 24) it is believed that Queenie was a pet family name for Matilda Amelia Sefton, born November 3, 1868 at the Brunswick Pier Hotel in Sandridge (Melbourne). Her mother was Matilda Sefton nee Aram, and her father was George Sefton, a publican across a number of hotels in Sandridge and Melbourne, and an event caterer of good reputation. Matilda had an older sister, Minnie Matilda Sefton, born in 1867.

From a combination of sources (see more detail at reference 24) it is believed that Queenie was a pet family name for Matilda Amelia Sefton, born November 3, 1868 at the Brunswick Pier Hotel in Sandridge (Melbourne). Her mother was Matilda Sefton nee Aram, and her father was George Sefton, a publican across a number of hotels in Sandridge and Melbourne, and an event caterer of good reputation. Matilda had an older sister, Minnie Matilda Sefton, born in 1867.

“Miss Queenie Sefton, who plays clever little character sketches with the Bert Bailey Company, comes of a theatrical family on her mother’s side. Theis dainty little lady tells how she loved the stage and wanted to become an actress at the early age of five. Her dolls were her audiences, and the beach usually her stage, for there she could be alone and indulge to her heart’s content in her passion for acting. ‘With my little inanimate companions I used to spend many a tragic hour in childhood enacting scenes from Shakespeare, with whose works my mother made me familiar as soon as I could talk, and one on occasion, when I had stolen away for longer than usual, to the anxiety of my mother, I was found weeping over my favourite doll who was Juliet to my Romeo,’ she tells. Finding that it was useless to discourage her aspirations (her father was a sea captain and did not favour the profession for his favourite daughter), she was placed under the tuition of Mrs. G. B. Lewis, and made her appearance at the age of 10 as Nellie in “The Stepping Stones.” Miss Sefton has a fondness for light boy roles despite her extreme femininity.” (Mrs. Lewis was Rose Edouin, an actress, wife of circus and theatre entrepreneur G.B.W Lewis, and the leader of juvenile theatrical troupes who performed regularly at theatres such as the Melbourne Bijou in the early 1880s).

Solomon’s Royal Museum continued to bring in new novelties - Texas Jack the cowboy, and Jun Gun, an Australian aboriginal whose ‘curiosity’ was to be an albino and ‘The Floating Fairies’ which may have been some variation of the old ‘Floating Cupid’s Heads’ from the early Sphinx-principle days. John Solomon promoted himself, dubiously, as ‘the famous magician who was received most successfully in all parts of the world’, and joined with Messrs. Silvester and Cunard in reviving Silvester’s famous Grand Cabinet Seances. Mr Cunard played the banjo, Mrs Cunard-Gordon sang, and Professor Woodroffe continued to display his amazing glass-blowing feats.

All seemed well at Solomon’s Museum up to the end of March 1890, with the possible exception of Madame Zenobia who found herself in legal trouble for telling fortunes. The Sydney Morning Herald, reporting that the Museum had just installed an amazing new piece of apparatus in the basement – air conditioning - said that the Museum continued to attract numerous visitors. On April 14 the Australian Star reported “There is no diminution in the attendances at Solomon’s Royal Museum … Amphitrite continues to make those graceful dives and perform other natatorial gyrations…”

And yet, nothing is certain in show business. John Solomon had declared himself bankrupt on April 11 and a sequestration order was made against him. (8)

Evening News, April 23, 1890:- ‘The Royal Museum - Distributed – Royalty at a Discount’

Under the instructions of the Sheriff the contents of Solomon’s Royal Museum and Palace of Varieties [sic], George-street, were brought under the hammer yesterday. There were, it is estimated, about 600 persons present, and the bidding for the whole thing commenced with a bid of £100 by Mr. Cunard, Mr. Solomon’s manager, and ultimately reached £350, at which price a Mr. Aarons became the purchaser. This gentleman promptly proceeded to sell the various curiosities in single lots, and it is understood made a good thing of it. The objects consisted of the wax figures, in which department Queen Victoria realised 30s., army men being a little easier. There were also two organs, and two pianos, and the turnstile. The Museum building is now waiting for the “next, please!”

Under the instructions of the Sheriff the contents of Solomon’s Royal Museum and Palace of Varieties [sic], George-street, were brought under the hammer yesterday. There were, it is estimated, about 600 persons present, and the bidding for the whole thing commenced with a bid of £100 by Mr. Cunard, Mr. Solomon’s manager, and ultimately reached £350, at which price a Mr. Aarons became the purchaser. This gentleman promptly proceeded to sell the various curiosities in single lots, and it is understood made a good thing of it. The objects consisted of the wax figures, in which department Queen Victoria realised 30s., army men being a little easier. There were also two organs, and two pianos, and the turnstile. The Museum building is now waiting for the “next, please!”

And so Silvester and Cunard were out of luck, though not, it seems, without their illusion props. The site of the Royal Museum did not disappear – on Christmas Day 1890, it re-opened once more as the Australian Waxworks, with Ubini’s Performing Fleas as the star living attraction. It seems that the former owners of the Waxworks, Edwin Sohier and Richard Kretschmar were the phoenixes who revived the Waxworks, which continued to operate until the end of 1896, when the waxwork collection was re-located to the basement of the new Strand Arcade, two blocks away in George Street.

Move to South Australia

The Museum’s performers wasted no time. Professors Silvester and Cunard, together with Helen Gordon Cunard, Miss Sefton, Md. Zenobia the Gipsy Queen, Josephine the Magnetic Lady and even Professor Woodroffe and his steam glass-blowing engines, packed their goods and headed immediately for Adelaide in South Australia where, at the Industrial Buildings, 58 King William Street, they opened the “Palace of Wonders” on May 1, 1890. “The most attractive feature is the Amphitrite, the wife of Neptune,” said the Australian, “which is one of the chastest representations of a sea nymph ever exhibited. It is quite a novelty, and is admired by the whole audience … this entertainment is worthy of every support.” The magical attractions in the show, as well as Alfred Silvester’s performance, were the Amphitrite and Flavia illusions, Clio the Sketcher, and Echo the solo cornetist, which was another of Kellar’s mechanical figures lifted from the shows of J. N. Maskelyne. Alfred was mentioned as the Manager of Amusements.

Cunard, who was clearly the head of the troupe, was already an established figure with a good reputation in Adelaide, and the Express and Telegraph favoured the show with a fine review, praising the refurbished venue, all of the acts and pointing out Amphitrite (which again was said to be Cunard’s own invention) “represented by a very charming young lady, who to all appearances is swimming in water of the purest crystal. The ease with which every movement is accomplished is really marvellous … Mr. Cunard is a very capable banjoist … Professor Silvester performs numerous feats of legerdemain …” Business was good and “Quiz” said that the Palace was “drawing in the shekels and will enable Cunard by-and-bye to buzz his long-looked-for mansion on the Lake of Como.”

An advertisement appeared in the Express of June 14, saying that the Palace of Wonders was for sale with all its apparatus … Mr Cunard is leaving for America July … contact Mr E. D. Davies [who was a ventriloquial performer]. This did not happen – the Palace continued at Adelaide with success for weeks to come. In July a new illusion was introduced, titled “Faith”: (9)

“… It was shown on Thursday afternoon in the presence of His Worship the Mayor of Adelaide … and a large audience. On the rise of the curtain a large cross is seen, and a voice is heard singing Gounod’s beautiful ‘Ave Maria.’ Then suddenly appears as a vision a lady representing the character of Faith clinging to the cross, and it is she who is singing. At the close of the song the figure suddenly disappears in as mysterious a way as it appeared, and to the surprise of the audience another figure dressed in flowing white robes is transfixed on the cross. The illusion besides being clever is beautiful, and it would be well worth one’s while to pay a visit to the Palace of Wonders to see it only. Miss H. G. Cunard interpreted the character of ‘Faith’ and sang the ‘Ave Maria’. “

Silvester’s Anoetos scene was also produced, and Alfred introduced new items into his repertoire. After a strong showing in Adelaide, the Palace finally closed on August 24, and the company departed, this time for Melbourne at the Silvester’s spiritual home, St. George’s Hall.

The grand opening on September 6 featured two performances daily, with displays of the ‘Faith’ and ‘Anoetos’ illusions, Amphitrite, Clio and Echo, ‘Professor Alf Silvester the King of Cards’, Professor A. L. Cunard ‘Thaumaturgist of the Orient’, and Josephine and Ruby the two ‘shocking girls – the vital sparks’. Helen Cunard sang, Madame Pearl was the new fortune teller, and a series of attractions were described only in showman’s terms:-

The Giant Spider – which may have a woman’s head on a spider’s body, using a mirror principle.

Minniehaha or the Abode of the Queen of Naida

Corinth, a beautiful body of Light and Shade

Estate, a Phenomenon contrary to all experience

The Mermaid, a lovely creature of the vasty deep (apparently not ‘Amphitrite’)

The Giant Spider – which may have a woman’s head on a spider’s body, using a mirror principle.

Minniehaha or the Abode of the Queen of Naida

Corinth, a beautiful body of Light and Shade

Estate, a Phenomenon contrary to all experience

The Mermaid, a lovely creature of the vasty deep (apparently not ‘Amphitrite’)

It was an extensive entertainment, and the press spoke well of the performers, including Alfred (“Mr. Alfred Silvester, who received a thorough training in this line of business from his father – the Fakir of Oolu – is a distinct gain to the company”) And yet, in one of those unfathomable quirks of showbusiness, what played with enormous success in Adelaide did not draw the customers in Melbourne. “Punch” of September 18 said “… has not been an over-brilliant success with Cunard’s Mysteries. As far as the entertainment itself is concerned, we doubt very much if it could be improved upon. The sleight-of-hand by Silvester and Cunard, the glass blowing by Woodroffe and the various illusions were really excellent. We notice that ‘Faith’ &c. &c. are now being advertised for sale.”

Just a fortnight after opening, Cunard’s Palace of Wonders closed its doors through lack of public support. Back in Adelaide, a giant charitable event titled “Wonderland” was about to take place, raising funds for extra beds in a private hospital, and the Advertiser reported that the management had purchased ‘Faith’, ‘Amphitrite &c.’ though there is no sign that any of the company was engaged to present the illusions.

Missing Years 1891 – 1892

With the demise of the show in Melbourne, Alfred Silvester effectively vanished from public view, and the only news relates to the divorce case brought against him by Louisa, when he promised the courts to pay £2 weekly in support, ‘when he was engaged.’ No other trace of him has been located between October 1890 and December 1892, and the conclusion must be drawn that he had taken up some career in business, in the same way that he presumably made ends meet during 1889 before meeting up with Cunard. It is known that during the later years to 1907 he was a manufacturer of magic props, operated a marriage bureau and took on magic students but little detail is available. In January 1892, an ‘Alfred Sylvester’ is mentioned as witness in a court case and was then an employee of Foy and Gibson, a Melbourne department store.

Mr. Cunard and his wife shrugged off the collapse, and went to tour in New Zealand where Archimedes managed the Harvey Brothers Burlesque Company and featured Helen Gordon Cunard singing ballads and operatic selections. He had kept hold of the “Flavia” illusion and in a vestibule of the theatre, audiences could stand and view the marble bust turning into a live figurine.

1892 - The Silvester Troupe

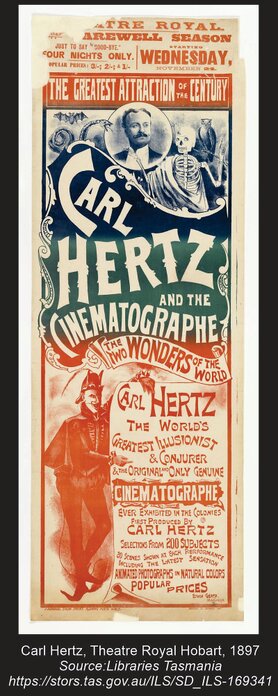

It is not until December 1892 that Alfred reappears, having taken the old Lyceum Theatre in Bendigo for a short season starting on Boxing Day. With a few dubious claims of having visited America, Europe and India during his ’17 years absence from the colonies’, Alfred re-fitted the hall with a stage and presented a variety and musical entertainment with a number of illusions including the Vanishing Lady, Anoetos, and Diana (a Lunar Mystery) of which the effect is unknown. The vanishing lady was later billed as “Straibouka” which the Bendigo Advertiser described: “In this a lady is seated in a chair on the stage and covered with a white sheet by the professor, when instantly at the firing of a pistol he lifts the sheet and the lady has disappeared, and a gentleman is seated on the chair, while the lady walks quietly up from the end of the hall.” The newspaper most likely had their facts slightly wrong. The Theatre Robert-Houdin, in 1888 had introduced an illusion, called “Stroubaika” “Strobaika” or “Stroubeika”, in which a man, shackled to a board rather than seated in a chair, changed to a woman. Alexander Herrmann and Carl Hertz also performed that illusion, and since Hertz was in Australia during 1892, performing both Stroubeika and Buatier de Kolta’s Vanishing Lady, there must have been some connection.

The short season was a success, and Silvester upgraded to the Royal Princess Theatre in January in conjunction with Gagino Brothers Crystal Palace Company. A “Cynthia Silvester”, only mentioned in a couple of occasions, performed the classic Sleeping Beauty (Entranced Lady). With the Gaginos, Alfred moved back to Melbourne and was seen at the Royal Hall, Footscray (billed as the Fakir of Oolu), and a full show at the Exhibition Building for a major ‘baby show’ exhibition.

1893 – South Australia

South Australia seemed to have an attraction for Alfred, both as a performing region and as a place to live. By the end of March, Alfred and Queenie had joined up at the Adelaide Bijou with “Hudson’s Mystical Musical Party” and was performing his spirit cabinet routine ‘La Salon du Diable’ and the Sleeping Beauty illusion. Among many musical, comedy and dance acts, Mr. Cunard and his wife Helen were again part of the troupe. Also on the show was Professor A. de Lacy with his ‘electrical automaton’ named Ali.

The season ran successfully to the end of April 1893, and Alfred produced the Fairy Fountain in the last weeks. Now dubbed ‘Hudson’s Surprise Party’, and without the Cunards, the show moved to Broken Hill where, for a relatively small population they managed to run a full month with good houses. Following this the Silvesters joined up with the Bijou Minstrel Burlesque Company in mid-May and remained at Broken Hill, giving a 20-minute performance of magic and the cabinet mystery, while Queenie took on a super-memory feat, the reading of messages from folded papers, and “Model Men”, the old Masks and Faces routine. The town must have suited the Silvesters, for they were still there to the end of July, now with the “Gaiety Group”.

South Australia now became Alfred’s home base and would remain so for the rest of his life. Looking forwards and back across his career, Alfred had become an intermittent performer after about 1878. Whether this was by inclination or lack of opportunity is difficult to determine. He must, of necessity, have had secondary business interests and it is known that he operated a marriage bureau and took another publican’s licence in later years, as well as one significant new career direction. The larger features of his shows tended to be the ‘standards’ from his father’s repertoire – Anoetos, Sleeping Beauty, the Enchanted Canopy, and the Davenport cabinet routine, along with his extensive range of smaller stand-up magic. All of these properties required to be stored and maintained, and from his reviews there is never any indication that Alfred gave less than a quality performance; if he was not constantly on the road he was, at least, prepared to give a show at any time. Alfred also built and presented a range of illusions of the ‘static display’ variety.

A small insight comes from April 1893 when Alfred was once again brought before the Adelaide courts by his former wife, Louisa, on a charge of leaving her children without adequate means of support. Louisa had come from Melbourne to pursue her claim. In court, it was contended that the case should be dismissed because the two parties were not man and wife, though the prosecutor argued that they were. Alfred stated that “he got £10 a week, but had to pay three assistants, and this only left him £2 a week for himself. For some time past he had been unable to send money to his children … he had not been able to keep up the instalments as regularly as he would have liked. He had scarcely enough to keep himself in clothes.” Ultimately this case was dismissed, the court pointing out that the prosecutrix had given no intimation to the defendant that she was in need, and had not written or telegraphed from Melbourne.

As will be seen, Alfred Silvester was to become a familiar face to South Australian audiences and had a considerable influence on many other magicians, as a mentor and tutor.

1894 began with several weeks performing in Port Pirie, and the ‘Standard’ of February 15 mentions some parts of the repertoire which are unfamiliar. Queenie was performing her memory routine, Masks and Faces and thought transmission, while Professor Silvester introduced his ‘Fairy Aquarium’ (perhaps the Amphitrite illusion), an experiment with earth, air, fire and water, and his “Demon Umbrella” which is unknown. It is interesting to note that Alfred, on occasion, still performed the full “Sleeping Beauty” illusion with the apparent removal of both supports. Alfred made a claim to have performed before the Shah of Persia, which sounds like a bogus publicity statement until it is remembered that his father had indeed performed during the Shah’s visit to Britain, likely assisted by his son. At the Town Hall in Port Augusta, Alfred’s performance of the Sleeping Beauty was shown in the guise of “The Fakir of Oolu”. Houses were good, as ‘The Silvesters’ as they were now billed, moved through regional townships.

Back in Adelaide during June, Alfred was engaged at the Theatre Royal and presented a range of illusions, some under mysterious names which conceal their effect. “Vidella, the three-headed nightingale”, “Amphiarous” which may be Amphitrite, “La Quatorzieme, the “Firefly Ballet” and the “Myriad Dance” were all on the bill, and we said to require alterations to the theatre. The Fairy Fountain, of course, continued to be a feature attraction at the Royal, and at the August ‘Carnival’ season. Further performances were seen at Port Adelaide, and then in late December Alfred jumped on the bandwagon of illusionists giving exposures of the spiritualist Mrs. Mellon, whose activities and demise have been covered in the essay “Hosking, Davis and Barker – Spookbusters”

For Alfred it was simply a matter of revamping his well-established Spirit Cabinet routine, and he rounded out a successful year producing spooks at the Bijou Theatre.

The years 1895 and 1896 (the year in which Alfred’s brother, Charles, died) follow a similar pattern. Alfred would pop up in some regional part of South Australia, giving his magic and anti-spiritualistic performances either in collaboration with Queenie, or as part of some ensemble show. Queenie also kept up her acting skills by taking stage roles in various local dramas. A small sidelight in January 1896 (11) was the sale by auction of a number of theatrical settings. A wonderful Fairy Fountain ‘used by Professor Sylvester, Fakir of Oolu’ was presumably one of the early models, and various Panorama paintings were sold including the Overland Route to India which had been featured by the Silvesters.

1897 – The Cinematographe and Biolographe

A revolution was on the way, though it began slowly. In August 1896 magician Carl Hertz returned to Australia via South Africa, bringing with him a brand new creation, the “Cinematograph Camera” which he had obtained from Robert W. Paul. The complex evolution of early cinematic devices, ranging from Edison’s “Kinetoscope” unpatented outside the U.S.A, to the Lumiere Brothers’ contemporaneous inventions, to Paul’s moving picture device in Britain, makes for competing claims. The Kinetoscope had been seen in Sydney as early as 1894 but only provided viewing for a single person at a time. What is certain is that Carl Hertz was the first person to introduce projected “living pictures” to Australia, in August 1896 at the Melbourne Opera House. The new device, always mentioned as “Lumiere’s”, was an enormous drawcard, and the ‘Free Lance’ (12) remarked “… with it and the phonograph, a manager will be able to give a whole variety show, carrying it in a box, and saving all wages. Alas! A bad time is coming for pros.”

Hertz featured the Cinematographe alongside all his stage illusions, and by January of 1897 he was at the Theatre Royal Adelaide, which was under the direction of famed theatrical manager, Mr. Wybert Reeve. While Hertz gave his card tricks, ghostly rapping hand routine and “Stroubaika” illusion, the person who introduced all the short moving pictures was none other than Alfred Silvester. “… received with unmistakeable favour, the frequent demand for another view taxing the ingenuity of the interpreter in ringing the changes upon the necessarily monotonous phrase ‘the picture will be repeated.” [Advertiser, January 4]

The short films included a seascape, views of cyclists in Hyde Park, and a scene taken at the Melbourne Cup Carnival. The intersection of Silvester family history cannot be overlooked here – Alfred Silvester senior had started his own career by creating photographic scenes for the amusement of the public and, had he been alive, would surely have been one of the first to take advantage of the new medium. Alfred1, Charles Silvester, and Alfred2 all had considerable experience with the use of limelight and the projection of lighting for their “Fairy Fountain” illusion.

Following the Theatre Royal season, Reeve and his partner Sestier sent their own cinematographe touring around South Australia (up to Broken Hill) and then through western towns of Victoria up to May 1897, and Silvester was one of the projectionists during this time (13) As competitors jumped on the bandwagon, Reeve would find himself by year’s end working against nine touring camera operators; by August Alfred Silvester had managed to acquire his own Lumiere Cinematograph and returned to Broken Hill under his own control. Advertising on August 19 he said, “Notice – the Lumiere Cinematographe is the premier and most powerful and perfect instrument in the world. There are but two in the colony – one the sole property of Wybert Reeve Esq. (lessee of Theatre Royal, Adelaide) and the other, as above advertised, under the management and direction of Professor Alfred Silvester.” There were, however, other versions of the cinematographe, in fact Mr. James McMahon was at Broken Hill on August 18 with his own machine. Silvester’s claim was that the Lumiere device was significantly more advanced, and at much less risk of fire breaking out - though even his projections were marred by a heavy flickering of the picture which made it difficult to watch in comfort. His lighting was said to use the ‘Etho-oxygen Gwyer light’.

Alfred had no less than thirty short films, some of them coloured, ranging from French and British scenes to the taming of wild horses in Mexico, the Holy Shrine in Jerusalem, the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee procession, and a Spanish bull fight. Silvester was the commentator, and appropriate music was provided by a small orchestra.

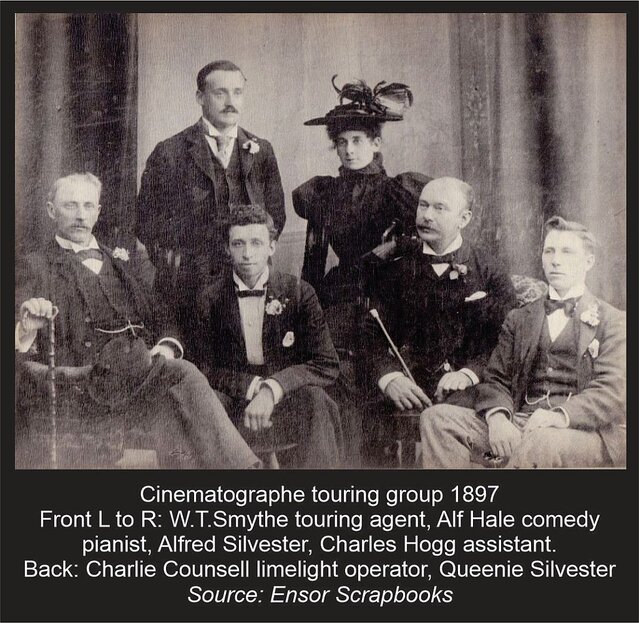

With such a novelty, Silvester was pulling in big audiences, and he took on an advance agent, the popular Mr W. T. Smythe, to guide his travels around South Australia, taking in Naracoorte, Mt. Gambier, Port Augusta and Mount Barker amongst others. At all these places the reception was large and enthusiastic, the halls often crowded to the doors.

By mid-November, Alfred was back at Broken Hill, now advertising both the Cinematographe and ‘the marvellous Biographe’ which might be thought to be the American machine of that name; however, Alfred wrote that his was a British creation. (14)

He rapidly consigned the Cinematographe into the background in favour of the newer machine which was able to project an image filling the entire stage and gave far less flicker. For his season at the Town Hall, he included a performance of magic including the “Aerialist’s Dream / Sleeping Beauty” with Queenie Silvester. He wrote to the ‘Barrier Miner’ – “I have visited the Hill on previous occasion with the ‘Lumiere’ Cinematographe with brilliant results; even with opposition from other comparatively toy machines of the same name … I have further invested in an apparatus of an improved nature on the Biographe, and it is the only instrument of its kind in the colonies, surpassing anything hitherto attempted. Therefore, to impress the public of its superiority I shall ignore the name of Biographe, and in future it shall be known as the Biolographe.”

So it would be; in December the Biolographe moved into Adelaide, now with forty subjects which the Advertiser said “are shown in double the size of any other method exhibited.” Silvester joined forces at Christmas with Harry Cogill’s New Minstrel Company to expand the attraction of the show at the Bijou Theatre, and business was strong. Alfred moved to the Victoria Hall but after closing in January 1898 he appears to have given away the movie business. Later advertising for the “Biolographe” shows the names of George Cullingworth (May) and Alfred De Haven (August) before fading from view. The rest of 1898 sees no other mention of the Silvesters aside from some local dramatic performances by Queenie, and a charitable appearance by the duo in July.

1899 - Final Tour

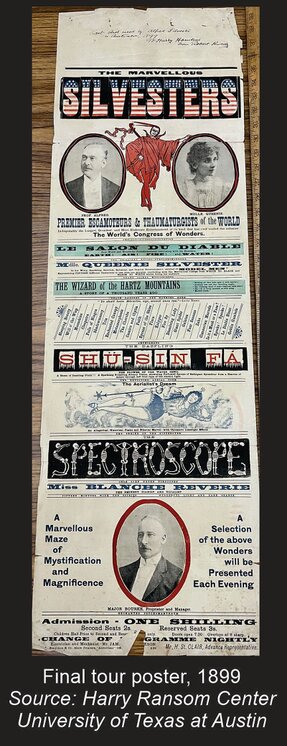

Alfred and Queenie had a final full-blown tour of South Australian townships in 1899, engaged by a well-known and respected ex-Army officer from Adelaide, Major Bourke, who had ambitions to head up a theatrical company. Newspaper reports invariably mentioned the Major who, apparently, had none of the less desirable attributes of most managers and advance agents; he was sociable and friendly, and most importantly he paid his bills promptly.

Alfred and Queenie had a final full-blown tour of South Australian townships in 1899, engaged by a well-known and respected ex-Army officer from Adelaide, Major Bourke, who had ambitions to head up a theatrical company. Newspaper reports invariably mentioned the Major who, apparently, had none of the less desirable attributes of most managers and advance agents; he was sociable and friendly, and most importantly he paid his bills promptly.The South Australian season, though lasting just a few months, gives an insight into how well prepared the Silvesters were to give a full evening show made up of the best items from their repertoire, and the press coverage was unanimously enthusiastic. Starting at Mount Gambier in mid-March, the Silvesters went through Narracoorte, Millicent, Border Town, Port Pirie, Quorn, Petersburg, and Broken Hill until late May.

“The legerdemain performance comprised a number of skilful tricks, and representations of different faces was well given, the spiritual seances were performed with success, and the Aerialist’s Dream… was as mystifying as ever.”

“The entertainment on the whole is an exceedingly clever one, and deserves all the patronage which can be bestowed on it.”

“The programme promised was one of mystery, mirth and beauty … the reputation of Professor Alfred and Mdlle. Queenie Silvester is too well known to need any comment … it was confidently anticipated that the show would be a good one, and in this expectation their numerous patrons were not disappointed.”

Major Bourke was said to be moving towards Tasmania. Alas, in stark contrast to the news reports of good audiences, quality performances and high reputation, we have a single sad commentary in the magicians’ magazine “Mahatma” (15) of October 1899:-

“Alfred Silvester’s show went on the rocks, Major Bourke losing heavily by the venture.”

Major Bourke did continue into Tasmania, but he engaged a variety company which played around the northern towns until July. For their part, the Silvesters were not quite done; they moved to Mount Barker, where they were seen on several nights until the end of June.

Since this was, for all purposes, the last tour of Alfred Silvester Silvester, a full review of his show as it was seen by the people of Quorn is reproduced here:

Port Augusta Dispatch, Newcastle and Flinders Chronicle Friday April 14, 1899

The Silvesters and Sisters Cambry. At Town Hall, Quorn, Saturday Monday April 8 and 10.

“It has been pointed out in these columns before, that when a talented company such as the one now under review comes to a town to perform, having been heralded by criticisms in various newspapers previous to their arrival, the chief difficulty is to report upon their doings without committing the journalistic offence of "pirating" and tautology, and to do them justice without seeming to reflect upon the abilities of previous troupes. In this instance, however, the latter danger is but slight because of the unique and extraordinary character of the items produced being quite different in every respect to any entertainment that has been presented to a Quorn audience for some considerable time past. The overture was begun by the young lady who acted as pianiste throughout the entire performance, and the hearty and genuine applause that rewarded each number of the programme must have assured the talented company that their efforts were thoroughly appreciated. Miss Osborn's rendition of the overture was so good that the somewhat unusual course of demanding an encore was taken, and - with real good nature - that young lady responded with a lively "break-down" which put the audience en rapport.

The curtain having been raised the stage was found to be hung with dark maroon curtains, in the front of which stood a small table. On the table were two candles burning and two empty glass water-bottles. Professor Alfred Silvester came forward and was well and heartily received. He commenced his performance of some very clever feats of legerdemain by causing a red silk handkerchief to fly from one of the glass bottles that had stood on the table and which he held in his hand - standing at some distance from the table — into the other bottle. This he followed up with a highly interesting performance with some money and a pack of cards. Having borrowed four coins from among the audience, be placed them in a long celery glass. He then walked among the people and got four of them to select one card each and not to let him see what the cards were. These selected cards were then placed in the pack by the people themselves and shuffled. The Professor returned to the stage and placed the pack in an upright card-stand. After waving his magic wand, he made the money in the glass tell what cards had been drawn by the audience and by mesmeric passes over the card-stand, caused the selected card to rise out from among the others; which upon being exhibited to the persons who drew them were declared to be the correct ones. This was most clever, but when the last drawn card rose and was shown to the drawer that gentleman declared that the one he drew was "a spade" whereas the card that rose was a "diamond." However, the Professor maintained that the money was right; and, then, to the utter astonishment of the audience, while the Professor held the card in his hand, well held up to view of all, the colour changed very gradually - just like a dissolving view - and the "spade" appeared on the same card. This extraordinary performance was loudly applauded. The money was made to reply to many questions which caused roars of laughter all over the hall. Professor closed his legerdemain with some very clever manoeuvres and handkerchiefs borrowed from the ladies, previously to which he had borrowed a gentleman's hard felt hat and from it extracted a large ball which fell with a heavy thud upon the platform, evidencing its weight and solidity, and a full suit of baby linen, and finally 15 hand-bags as large as the hat itself, all of which were piled upon the table, so that the owner of the hat received it back if he was not light headed - as the Professor said he would be - the Professor was not to blame.

Miss Ivy Cambry then sang "What does she know about a railway?" This lady, as well as her sister Rose, is a very talented young actress - makes up to her part exactly and does not over-rate it. Her singing, unfortunately, could not be done full justice to, because of the bad acoustic properties of our stage, but she earned the very hearty encore she received — and, more so by the splendid dance she executed in response.

Miss Queenie Silvester then appeared, and after giving a very instructive lecture upon moustachious — from the appearance of "the down" to the full growth — kept the attention of the audience well in hand while she, in 15 minutes personated as many different well-known men's faces; loud applause rewarded this lady's clever performance. The Cambry sisters brought the first part of the programme to a close with a duet and dance. The duet was named, "You show me your slate," and was splendidly rendered, thereby adding to the very favourable impression that those ladies had made, and the dance and high-kicking at the end of each verse were much admired by a great many — especially at the back of the hall. After an interval of ten minutes Miss Osborn again played, in a highly satisfactory manner, an overture, and if the old piano had any music left in it, Miss Osborn proved herself the one to bring it out as the instrument acquitted itself well. Miss Rose Cambry then sang "Cast aside," a song full of pathos as the title suggests. She sang clearly and distinctly, and in her gestures illustrated the meaning of the words fully. An encore was promptly responded to and a hearty applause followed. Professor Silvester then gave an exhibition of a very severe test of the rope-tying tricks. Having explained the nature of the exhibition and its difference from that of Anna Eva Fay, that in this the piece of rope used is short, and in the other long, and the ends of this one sewn and tied, he called for some well-known person to come forward and tie him up. Mr John Cahill responded to the invitation with that promptness and courtesy for which all his countrymen are so famous, and no one is better known in Quorn than John Cahill. He proceeded to tie up the Professor, and one could see by the wincing of that gentleman that John had got him in the grip of a "rale Oirish knot." Having satisfied himself and all concerned that the Professor was secure, John stepped aside and the Professor entered the cabinet and immediately his two hands were seen over the top of the cabinet "untied," and he struck a match and lit a candle and then instantly came out but his hands were still tied and Mr Cahill said the cords had not been touched. The next performance was with the bells and tambourine, and the Professor came out with his coat off, and asked Mr Cahill to lend him his. This being done the Professor entered the cabinet coatless, but instantly reappeared with Cahill's coat on, but still his hands were tied — so John said. The security of the tying was proved by the difficulty Mr Cahill had in untying the performer at the close of the seance. Loud applause greeted this really wonderful exhibition.

A duet by the sisters Cambry followed, entitled "I'll tell mamma on you," Miss Rose appearing as a youth, and Miss Ivy as a coy maiden. The singing was good, and the words catching and laughable, and so doubt the attitudes of the pair exceedingly tantalizing to some of the lads. An imperative encore was the result to which the ladies generously responded. The performance was brought to a close by an allegorical, historical, and ethereal marvel, with chromatic limelight effects, in which Miss Queenie Silvester was put into a trance by Professor Alfred Silvester, and while in that state placed in various positions and adorned with suitable draperies by which the following tableaux were placed before the enraptured audience, viz — sleep, skipping, flower girl, Red Riding Hood, girl playing tambourine, prayer, Ireland, United States of America, Britannia, repose. The "entranced" lady was then placed in a horizontal position and Professor Silvester passed a rod all round her body to prove that there were no strings or wires to support her. The effect of the performance was enhanced considerably by the clever manipulation of the chromatic lime-light instrument by Mr J. D. Clarkson, The "National Anthem" brought a much-enjoyed entertainment to a close and repeated wishes for a speedy return of their visit. This criticism would be quite incomplete without a reference to the genial and gallant proprietor and manager, Major Bourke. It is only necessary to be in his society for a very short time indeed to be attracted by his bonhomie and genial presence, and to be assured that one is in the presence of a real gentleman — an ex-English military officer — and one that will always do his utmost to please his numerous patrons by placing before them such entertainments — performed by the best available talent — that will never fail to give entire satisfaction and genuine wholesome pleasure. The same remarks apply to every member of the troupe.”

Final Call – Retirement and The Tivoli

From this point, with one exception, Alfred and Queenie called a halt to performing. That Alfred had other irons in the fire is shown by a report (16) that he had become the manager of a hotel around October 1899.

From this point, with one exception, Alfred and Queenie called a halt to performing. That Alfred had other irons in the fire is shown by a report (16) that he had become the manager of a hotel around October 1899.“A large number of my readers no doubt remember the best cinematograph that visited the Peninsula and surrounding country under the able guidance and management of Mr. Alfred Silvester, who in his quiet and dry jokes at the exhibition of the pictures created so much amusement – will during the holidays or any other time while in town they can see the noble specimen of dry humour managing the Family Hotel in Currie-Street, where he has been for about two months. Alf is well liked by everybody, and is doing a roaring trade.”

It is known that Alfred took on the operations of a Matrimonial Agency at Globe Chambers in Victoria Square, around 1901-1902. According to historian Harrie Ensor, he also ran a ‘magic manufacturing shop’ at some point, though no physical shopfront is known.

Relying on the public record for information, little is seen of the Silvesters for several years, except that, in May 1900, Alfred wrote a series of six explanatory articles on magic tricks for the Adelaide ‘Express’ (19), which are included in the Appendix to this history. Alfred doubtless would have gone to see his daughter, Violet, when she appeared in Adelaide on several occasions under the direction of the J. C. Williamson organisation.

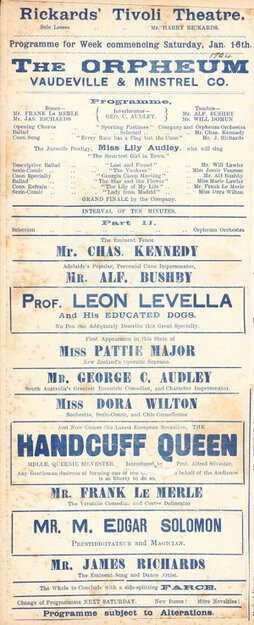

In late December 1903, however, Alfred and Queenie were suddenly in the spotlight again. Over the Christmas period, Harry Rickards’ Tivoli Theatre presented an “All-Star Specialty and Minstrel Company”, and the pair were featured with the “Sleeping Beauty” illusion, for which ‘Quiz’ reported that they “received unstinted applause, for the performance is a graceful and mystifying one.”

Sliding without interruption into 1904, Queenie now took on a role as a “Handcuff Queen” at the Tivoli, with Alfred acting as the front man. Queenie was shackled hands and ankles with nine regulation handcuffs and, behind a screen, made her escape while Alfred covered the inevitable stage wait. The Silvesters were at the Tivoli all through January, and it seems that entrepreneur Rickards had awoken to the escape act of Harry Houdini overseas, as he engaged not only Miss Silvester, but the escapologist Cirnoc for his theatres. Robert Kudarz, writing for “Magic” magazine in May 1904 said, “Queenie Silvester, a clever lady in illusion business which, as you know, is so closely connected with the Silvesters. I doubt very much if one could find in the Australian Colonies a person who knows so much about magic as the same Prof. Alfred Silvester, or one who could present such a complete illusory entertainment – if he liked.” Kudarz sent portrait photos of the Silvesters to Harry Houdini, jokingly inscribed on the back “Queenie Silvester, Houdini’s first imitator in Australia.” (17) Houdini, doubtless, was not amused.

A brief appearance in 1905, with much the same variety company as had appeared at the Tivoli was advertised to once more feature the “Sleeping Beauty” illusion, and the magical career of the Silvesters came to a close.

At Adelaide Hospital on June 15, 1907, at the age of fifty-four, Alfred Silvester Silvester died following a stroke. He was buried at Adelaide’s West Terrace Cemetery (18) in a service attended by numerous old representatives of the theatre and Tennyson Dickens, son of novelist Charles Dickens. No headstone marked the grave, possibly indicating some financial constraints. In 1911 Alfred’s sister, Daisy Silvester/Ball, paid for a lease on the plot until the year 2010.

‘Quiz’ said, “For geniality of character and bonhomie the deceased was hard to beat. His many kindnesses for the sake of charity and helping his brother professionals was proverbial.”

Robert Kudarz memoralised in The Sphinx magazine [September 1907], “… he gave much of his time and talents to charity, and he became one of the best known of entertainers. Alfred Silvester was both a conjuror and an illusionist, and his knowledge of things magical, optical, mechanical and mystical was very extensive; more so, I believe, than any other magician in the country. His entertainment, as I saw him for the last time produce it in Port Adelaide in 1889, was the best I witnessed while in Australia, and I have not seen it equalled yet by any colonial performer. In private life Prof. Silvester was a genial, good-natured, unaffected man, and there are many amongst us who will regret his end. Vale, Silvester! Sweet and peaceful be thy rest.”

Queenie Silvester's later career

Queenie was only in her thirties and, strange as it may seem, her years with Alfred Silvester would prove to be just the curtain-raiser for her main career. She continued to act on stage after Alfred’s death, playing light comedy roles to good reviews. In 1909 she married George Neville Kensington, who became the stage manager for the Bert Bailey Dramatic Company. Of note is that Queenie’s sister, Minnie, was married to John Fanning, the Touring Manager for the Bailey company; she died in 1925.

Queenie was only in her thirties and, strange as it may seem, her years with Alfred Silvester would prove to be just the curtain-raiser for her main career. She continued to act on stage after Alfred’s death, playing light comedy roles to good reviews. In 1909 she married George Neville Kensington, who became the stage manager for the Bert Bailey Dramatic Company. Of note is that Queenie’s sister, Minnie, was married to John Fanning, the Touring Manager for the Bailey company; she died in 1925.Bert Bailey, born in New Zealand in 1868, and himself a magic enthusiast, had written a play with Edmund Duggan titled “On Our Selection”, based on the short stories by Steele Rudd. After the play opened in Sydney it became a runaway success, an oft-repeated production, and something of an iconic representation of the stoic Australian bush life, featuring the famous characters known as ‘Dad and Dave’. Bailey’s Dramatic company played this, and similar drama/comedies for years to come, reviving “On Our Selection” on stage, and Bailey not only played the part of ‘Dad’ thousands of times live, he later made several movies based on the ‘Dad and Dave’ characters. He would die a wealthy man in 1953, having made an estimated £200,000 from On Our Selection alone.

Queenie was in it from the start, having reverted to her former title of Queenie Sefton. She created the role of “Mrs. White” (Dave’s mother-in-law) in the debut season, and was seen as late as 1928 in revivals of the play, in the role of Lily (Dave’s sweetheart). She played in other Bailey productions such as “Squaw Man” and “The Squatter’s Daughter.” Queenie Sefton died on August 28, 1953 probably aged 85, and her ashes are interred (as Queenie Kensington) at the Eastern Suburbs Memorial Park in Sydney.

Alfred Silvester’s Influence

“There is no doubt that Dr. Sylvester aided immensely the stabilising of many of our early Australian magicians, an attribute carried on by his son Alfred until the time of his death during 1907.” – Will Alma, Magic Circle Mirror, February 1974The importance of Silvester’s career cannot be measured by his public performances alone. While he had a disjointed professional career, there is a story to be told about his influence on other Australian magicians, and some intriguing clues about where his illusion props ended up. Will Alma’s statement that the Silvesters “aided immensely the stabilising of many of our early Australian magicians” is accurate; for over thirty years the Silvester brand was a constant feature of theatrical life and, through their teaching, mentoring and prop building we can trace the Silvester legacy across a number of Australian magicians, both amateur and professional, extending well into the 1900s. As writer Robert Kudarz said, Alfred Silvester bridged the period between the old “glass and trapdoors” era of illusion and the newer style of stage magic which evolved into the deceptive creations of P.T. Selbit, Charles Morritt, and today’s modern illusionists.

We are indebted to several magicians who left notes about Alfred2’s behind-the-scenes work in magic. (19)

We are indebted to several magicians who left notes about Alfred2’s behind-the-scenes work in magic. (19)

Percy Verto (George Jacob Haussmann 1870-1936) was a New-Zealand born magician touring under the name “Prof. Haussmann” until he became “George Percy Verto”, best known for his escapology.

Percy Verto (George Jacob Haussmann 1870-1936) was a New-Zealand born magician touring under the name “Prof. Haussmann” until he became “George Percy Verto”, best known for his escapology. His potted biography in “The Imp” magazine says “When a lad I was assistant to Prof. Haselmeyer, Prof. Anderson [mentioned as the Wizard of the North, but must have been the later Anderson], and Prof. Alfred Sylvester [presumably Alfred2], all when in New Zealand … In my early days I carried as much as two tons and a half of magic and illusions. I was always scared when once I carried the Pepper’s Ghost illusion of having the plate glass smashed, but I got through … had lots of worries with large plate glass illusions such as Vanity Fair and Protean Cabinets, and many others.”

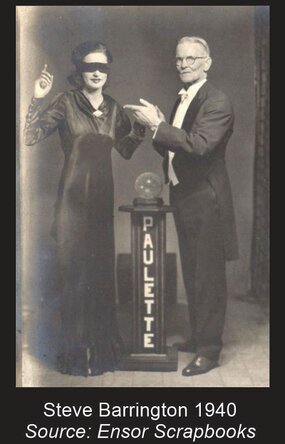

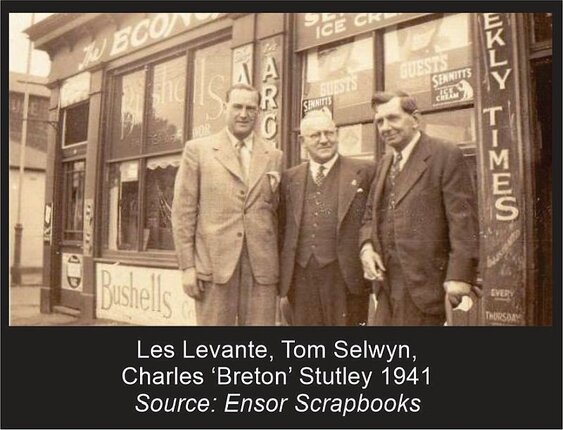

Steve Barrington was a magician from Broken Hill, an important accumulator of notes about visiting magicians, whose collection of ephemera was shared with historian Harrie Ensor and formed a central part of 'The Ensor Scrapbooks'.

Steve Barrington was a magician from Broken Hill, an important accumulator of notes about visiting magicians, whose collection of ephemera was shared with historian Harrie Ensor and formed a central part of 'The Ensor Scrapbooks'.Barrington performed professionally as 'Du Barrie' and 'Carlbert'. In December 1901 he received a letter from Alfred Silvester (headed from the Matrimonial Agency in Globe Chambers) saying “Dear Sir, Hearing that you are in the magical business, I beg to inform you that I am a manufacturer in that line, and have supplied many professional and amateur conjurers – if I can do any business with you, I shall be most happy… ” From that letter, Barrington became a pupil and friend of Silvester, continuing as a performer into the 1940s. South Australian magician Ephraim Ernest ‘Jim’ Bennier (“Louis Bretto”) and Kirkham Evans were also pupils of Silvester, and Lewis Cohen the Mayor of Adelaide learned coin magic with him.

Thomas “Anglo” Horton, according to Steve Barrington “was a pupil of Sil’s who taught him conjuring and magic in conjunction with his juggling which he excelled at. Anglo leased the Adelaide Tivoli – under Silvester’s management [1902] and got a lot of publicity so he could use same in London. He failed to click in London, although he managed along at the ‘second’ theatres."

Sadly, Horton ran off the rails – he shot his wife in the main street of Adelaide and was executed in May 1904. His story has been told in the book “Unbalanced – The Rise and Fall of Anglo the Juggler” 2023 by Barry Thorson / Niels Duinker.

Sadly, Horton ran off the rails – he shot his wife in the main street of Adelaide and was executed in May 1904. His story has been told in the book “Unbalanced – The Rise and Fall of Anglo the Juggler” 2023 by Barry Thorson / Niels Duinker.

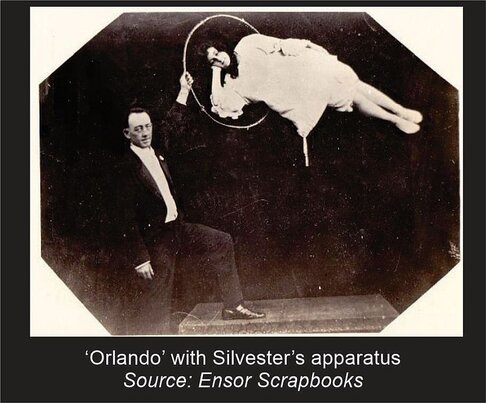

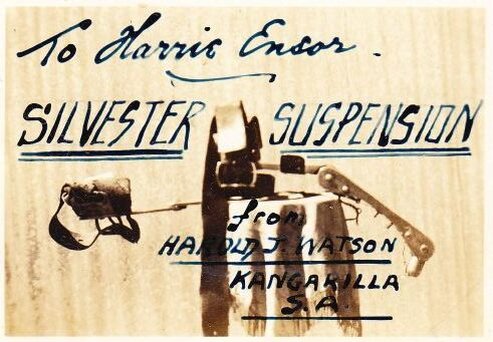

The Trail of the Entranced Lady

The “Entranced Lady” illusion, otherwise known as “The Aerialist’s Dream” or “Sleeping Beauty”, was the mainstay of Alfred1, Alfred2 and Charles Silvester, and later of Alfred3. It is difficult to trace the ownership of the original mechanism, and certainly there must have been several mechanisms made, but the possibility exists that the first prop, obtained second-hand in America in the 1860s, might have been obtained by Alfred2 after the death of his father in 1886. Additional confusion is caused by the references over the years to improvements to the illusion, which allowed the assistant to firstly rise in the air by herself, and secondly to have her feet follow the magician as he walked around the stage. These ‘extras’ were not always performed but their mechanics remain a mystery. Alfred Silvester’s great claim to fame was, of course, the removal of the second supporting pole beneath the assistant’s elbow, leaving her apparently floating unsupported – and it is certain that this effect was produced with a “black art” background and a removable metal shell over the pole.

For posterity, if nothing else, these notes concern the later history of the apparatus, or at least one version of it. The ultimate fate of the prop is not known.

Adelaide magician Harold Watson wrote to historian Will Alma (20) “Alfred Sylvester ‘popped’ his Aerial Suspension to McDonald, theatrical outfitter, for £5 some time before his death. In 1915 “Orlando” (Fred W. Buik) purchased it for £5 and used it for several years appearing on old Star Circuit. (23) I purchased it from Buik for £4 in 1931, but never used it. The platform and masking cover were very heavy. During World War II Buik borrowed it for a patriotic concert party tour. The harness was not returned to me. “Queenie Sylvester” was written in indelible pencil on leatherwork. I still have poles (solid pole with half shell and wooden pole), socket to receive support and 4 turned legs to isolate platform from stage. I have a photograph of the body frame and will try to locate it. Sylvester advertised to teach mindreading act and Steve Barrington used it to teach Jim Bennier the act about 1905. [Bennier/Bretto appeared with Barrington/Carlbert as “The Boy Marvel”]

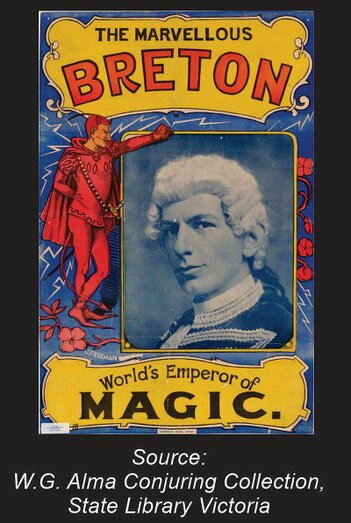

The Marvellous Breton

The last of the magicians known to have directly been mentored by Silvester was Charles Stutley, who performed initially as “Alberto” and later as “Breton”. While performing at Hudson’s Waxworks in Adelaide, he met Alfred Silvester probably around 1901.

On the reverse side of an old “Alberto” handbill, Steve Barrington wrote:

“Old program of Charles Breton now resident of Melbourne. ‘Sil’ [Alfred Silvester] taught Stutley (his real name) & myself in 1900 & at that time we were the only magis [ie, professionals in South Australia] – No am wrong, Emil Ruch was also in the business. Stutley adopted the name of Alberto but when Alberto [Harold McAuliffe] (now in U.SA) came to Adelaide to play Rickards Circuit, Stutley changed to Charles Breton.

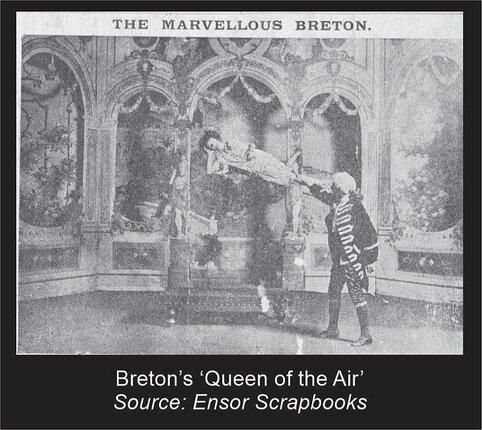

I got this program from a Mrs [Stalley], customer of the HS Store. She is a sister to Stutley & used to work in his Queen of the Air which was as you know Sil’s main illusion [ie, the Entranced Lady]. This show was Stutley’s first all night program & really a rehearsal prior to going on tour. He is the only S.Aus magi to travel his own “all night” show. Sil was the master brain behind it all & supervised & planned the manufacture of all the illusions. // Since writing the above Mrs Stalley …. tells me that she only worked in rehearsals at home & that Miss Knight, now Mrs. Emil Ruch worked for Alberto in all his public performances.”

Harrie Ensor wrote (20) that Breton bought a number of illusions from Silvester including the Production of a Lady from a Hat (which was originally introduced to Australia by Robert Heller and shown by Breton under the title The Woman in Red – see (21) ), the Enchanted Canopy (which Ensor incorrectly states was from Charles Morritt; but the Silvesters had used the trick since the 1860s), The Chevalier Thorn Double Table Vanish of Lady in Cabinet, and what Ensor describes as a “self-rising and revolving suspension built for Alfred Sylvester in 1904 … this piece of apparatus is now my [Ensor] property”. Whether Ensor was describing the Aerial Suspension illusion or some other levitation is not known; but Breton’s illusion titled the ‘Queen of the Air’ was the Aerial Suspension.

Charles ‘Breton’ Stutley was performing a Milk Can escape in 1909. He continued to perform until 1934, when rheumatoid arthritis forced his retirement from the stage. He became a cinema projectionist; but his own experience would have been shared with his friends in magic, who included Louis Nikola, George Waldo Heller, and Les Levante – and so the knowledge is passed along.

Robert Kudarz on Alfred Silvester

The perennial correspondent for American magic magazines was Robert Kudarz, or Tom Driver of New Zealand, himself a capable magician. We conclude this chapter with Kudarz’s recollections and estimation of Alfred Silvester Silvester.

M-U-M magazine (Society of American Magicians) April 1920 –

“[Silvester] settled for a while in Melbourne, and imparted his knowledge of magic to quite a number of budding Australian magicians, among the number being Dr. Russell (22), Hector Lacie, the ventriloquist who afterwards travelled with S. S. Baldwin, and “Tregaski”, who gave up the occupation of ‘drummer’ [ie, agent] to become a “Magic Gift King.” Alfred Silvester was perhaps the first professional to teach magic and build illusions in Australia, and he was quite capable of doing so. He afterwards went to Sydney and presented quite a number of illusions in Solomon’s Museum, an unusually elaborate place of amusement at that period of the late 1800s – a kind of New York Eden Musee.”

“[Silvester] settled for a while in Melbourne, and imparted his knowledge of magic to quite a number of budding Australian magicians, among the number being Dr. Russell (22), Hector Lacie, the ventriloquist who afterwards travelled with S. S. Baldwin, and “Tregaski”, who gave up the occupation of ‘drummer’ [ie, agent] to become a “Magic Gift King.” Alfred Silvester was perhaps the first professional to teach magic and build illusions in Australia, and he was quite capable of doing so. He afterwards went to Sydney and presented quite a number of illusions in Solomon’s Museum, an unusually elaborate place of amusement at that period of the late 1800s – a kind of New York Eden Musee.”

M-U-M magazine May 1920 –

“Alfred Silvester was the first magician I met when I landed in Australia, as he was also the last man I shook hands with in Adelaide when I left for New Zealand. He had made his home in Adelaide and had presented his “Mysteria” in every nook and corner of South Australia. It was in the Port Adelaide Town Hall I had the pleasure of seeing him put on a show worthy of his illustrious father. Indeed it was the best magic show I saw in Australia. The Entranced Lady, Masks and Faces, the Protean Cabinet [probably the Enchanted Canopy] and the Prismatic Fountain were features of the entertainment which brought back pleasant recollections of the Fakir surrounded as it was with many of the original effects and appurtenances of the Doctor.

Alfred Silvester was the first showman in Australia to project an animated picture the full size of the proscenium with the aid of an improved Lumiere Cinematograph. He called it the “Biolograph”. Charles Morritt, the well-known English illusionist came to Australia with the [Biograph] and he was much surprised on opening in Adelaide [January 1898] to find the local “Biolograph” playing in opposition to the imported [Biograph]. He was not inclined to pay much attention to what local people told him about Silvester’s Biolograph being the equal of the [Biograph] but when Professor T. Kennedy, the hypnotist, who was also then in Adelaide [February 1898], corroborated the story, adding that in some respects it was superior, it made him concerned in the matter, and he went and “saw for himself”, with the result that he frankly admitted the invention of his countryman and brother conjuror was a “cute idea” and worthy of all the praise given to it, giving the tip that London was the place for it.

… In the death of Alfred Silvester … it may be said the “last link was severed” between the “old and new magic” which was beginning to bud at that time in Australia. I lost my dear old Australian “Magic chum”, while Adelaide lost a genial and kind-hearted citizen, who was ever ready with his wand to assist others for sweet charity’s sake.

As I write these words of Alfred Silvester, his son – also named Alfred – is in New Zealand, having come over from Australia under the Fuller management, and is about to present some of the tricks his father and grandfather showed us in the ‘70s!”

Kudarz was correct – another generation of Silvesters was embarking on a magical career of an altogether different style. His story will be told in Chapter 11.

REFERENCES FOR CHAPTER TEN

(1) The various ‘Cunards’ in Harry Kellar’s troupe are detailed in “Kellar’s Wonders”, by Mike Caveney and Bill Miesel (2003, Mike Caveney’s Magic Words). John Hodgkins was with Kellar in the early 1880s. The Indian Daily News does list Mr. A. Litherland Cunard along with Harry Kellar at Bengal on Feb.6, 1882.

(2) The connection between Solomon the auctioneer and the theatrical operator is confirmed by the Sydney Morning Herald, November 25, 1880 p.6

In September 1890 Solomon had a court case brought against him by the Royal Hotel, next door to his auction house. Solomon was alleged to have been shouting loudly, ringing a bell, and having a brass band play in order to attract customers! In other reports, he was stated to be more of a “cheap jack” than an auctioneer; in other words he sold cheap goods with a very high starting price which he gradually lowered to a quarter or less of the original asking bid.

In September 1890 Solomon had a court case brought against him by the Royal Hotel, next door to his auction house. Solomon was alleged to have been shouting loudly, ringing a bell, and having a brass band play in order to attract customers! In other reports, he was stated to be more of a “cheap jack” than an auctioneer; in other words he sold cheap goods with a very high starting price which he gradually lowered to a quarter or less of the original asking bid.

(3) See https://blogs.slv.vic.gov.au/such-was-life/the-marvellous-and-macabre-waxworks-part-one-the-more-murderers-the-more-it-thrives/ parts 1 and 2.

(4) The origins of Amphitrite are mentioned in H.J. Burlingame’s “Leaves from Conjurer’s Scrapbooks” and in The Sphinx magazine Volume 27, January 1929. Oscar S. Teale “The Evolution of Levitation” – Amphitrite was worked in several, different ways, but the best was said to have been that patented in the United States of America by Gustave Castan, September 11th, 1888, under number 389,198. It was also covered by letters patent in Europe, by Louis Castan and Gustave Castan, of Berlin. Amphitrite was also exhibited under the name of "MAGNETA."

The Castan patent application, #5254 (Berlin) is reproduced in

Will Goldston’s “The Magician Annual 1908-9”

(5) Lawsuit papers from Public Record Office Victoria,

https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/B8629FC8-FA1C-11E9-AE98-A3DAB81671B1?image=1

https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/B8629FC8-FA1C-11E9-AE98-A3DAB81671B1?image=1

(6) Melbourne Punch July 25, 1899 page 9

(7) Inquirer and Commercial News (Perth W.A) Jun 7, 1889