William Maxwell Brown - Goldrush Theatre and the Sphinx

"... he got stage struck, and that ruined him commercially." - Ballarat Star, November 23, 1889

Witness – “I have belonged to the theatrical profession for 43 years. Have played everything connected with the stage from leading man to prompter.”

His Honor – “And not crushed yet?”

Witness – “No, not crushed yet, your Honor.” - Express and Telegraph Adelaide, January 20, 1883

His Honor – “And not crushed yet?”

Witness – “No, not crushed yet, your Honor.” - Express and Telegraph Adelaide, January 20, 1883

INTRODUCTION

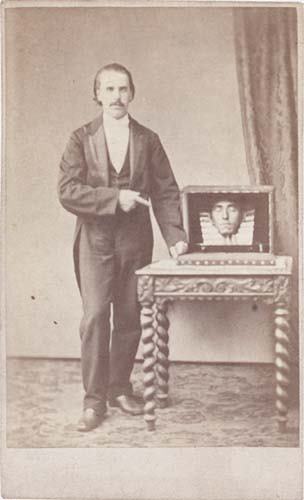

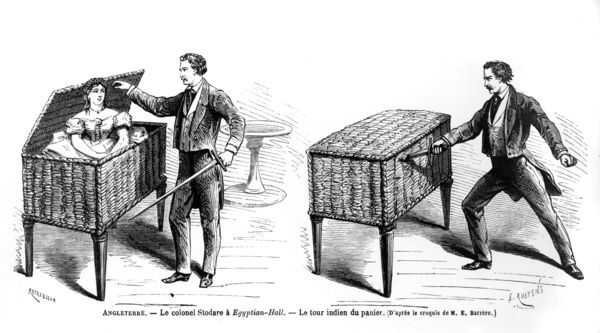

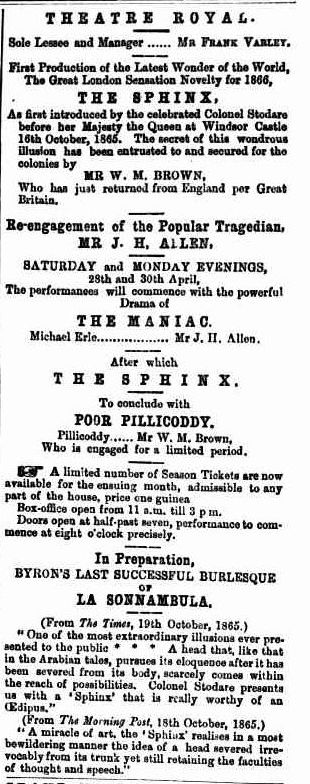

Initially, the career of William Maxwell Brown held out considerable promise in connection with magic in Australia, since he was the first to bring one of magic’s most iconic illusions to this country. It turns out that his association with magic, though ground-breaking, was relatively brief. However, Brown’s involvement with the development of Theatre in this country, particularly in his home town of Ballarat, proves to be a much more important feature. As an actor, theatre developer and manager, writer and local identity, he deserves far more prominence than the scanty mentions given to his name in theatrical histories to date. So, the story on this site highlights Brown as a worthy contributor to Australia’s theatrical life, in addition to his several appearances as a magician.

The essay will cover the life and career of William Maxwell Brown, but it is not an attempt to record every detail of his life. There are more family history details, more civic records at Ballarat and more stage plays featuring Brown, that could be unearthed. Using mainly the information available on the public record, we will address some of the aspects of his theatre career that should be more visibly recorded in history – and, of course, his place in the magic history of Australia.

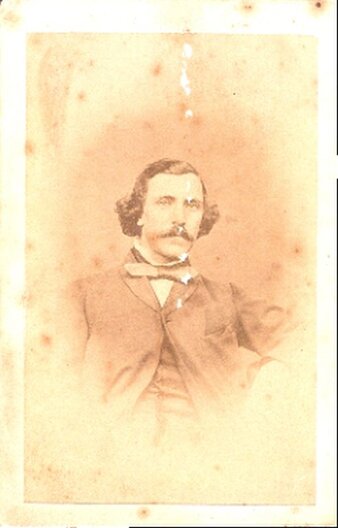

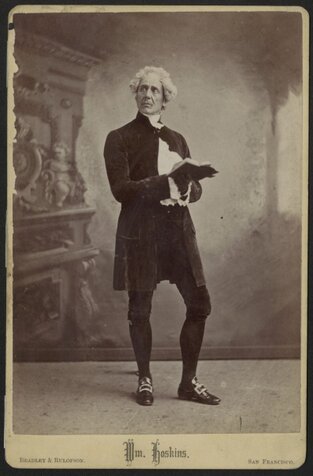

William Maxwell Brown, probably Ballarat c. 1854-1860

courtesy R.Sutherland

William Maxwell Brown’s life resembles a Roly-Poly toy which can be pushed over, only to rebound every time. He was not the greatest, nor the most famous actor of his generation, yet he appeared on theatre bills alongside some of the best. He never managed to have a consistently successful career either on the stage or in communal life, yet he was the driving force behind the development of some of Ballarat’s pioneering theatres. He was not a magician, yet he brought to Australia the ground-breaking “Sphinx” illusion for the first time. He was declared insolvent a number of times, yet he returned time and time again to the theatrical pursuits that he loved. Brown’s name is not prominent in the history books, but he can be found just behind the curtains of some of our country’s formative events.

Background

Although we will mostly follow the public record, some family genealogy is also useful, through the welcome assistance of Brown’s great-great-grandson, Robert Sutherland, who also provided the portraits shown. William Maxwell Brown (1831-1886) was the son of a Mariner, John Brown (wife Mary), and was born in Liverpool, England. He had a brother, Thomas, who will be featured in the story. William married Margaret McGuckin (1829-1882) in Liverpool, at which time he was making a living as a stationer and bookbinder, and later a grocer.

William Maxwell Brown (1831-1886) was the son of a Mariner, John Brown (wife Mary), and was born in Liverpool, England. He had a brother, Thomas, who will be featured in the story. William married Margaret McGuckin (1829-1882) in Liverpool, at which time he was making a living as a stationer and bookbinder, and later a grocer.Though the details are not clear, William was also associated during his time in Britain with the Nottingham and Surrey theatres, both as a performer and stage manager. In 1858 he would tell a court “I was stage manager at Nottingham at the time, and had been for two years before.” (1) There is also a possibility that he acted at Liverpool in amateur roles. As a young man in his early twenties, he might have been actively involved with the theatre, but would not have been playing any major acting roles.

However, on May 16, 1853, the Standard Theatre (Shoreditch, London) opened a production of “The Will and the Way, or, the Secret Vault and the Voice of Death” adapted by W.M. Brown, which would later become one of his mainstay productions in Australia. The story was not original with Brown; he had adapted it for the stage, based on a March 1853 tale in the London Journal by John Frederick Smith called Harry Ashton; or The Will and the Way. (3) Nor was Brown’s the only adaptation; the 1853 production opened simultaneously with three others around London, and there were more by other writers. In context, Charles Dickens was publishing his “Bleak House” novel at this time.

Emigration to Australia

William was not the first of the family to emigrate to the colonies. His brother Thomas appears in the township of Geelong, south-west of Melbourne, as early as August 1852 (11), where he had set up as a bookseller and commercial stationer at Market Square, Moorabool Street, near Malop Street. Unlike some of our other magical subjects (Courtier, Du Pree, Wilton) there is no indication that either Thomas or William had any convict connections; and given that Victoria’s goldrush history started around 1851, it is likely that Thomas had moved to Australia to take advantage of the money flowing in the colony – not by taking his chances as a miner, but by selling to the local populace.

Probably receiving an invitation from his brother to “come on in, the water’s fine”, William arrived in Australia on August 1, 1854 as “W.M.Browne”, aboard the square-rigged ship ‘Carpentaria’ carrying 542 second and third-class passengers, after a passage of 79 days. With him were wife Margaret (listed as age 24), daughters Jane (age 1) and Frances Mary (age 2). William’s age was shown on the register as 26 but he was near to 23.

Other children were born to the Browns in years to come (4), and although it is not known when she arrived, William’s mother Mary also came to live in Australia; her death notice in early September 1872 (5) noted that she was at her son’s residence in Errard Street Ballarat, and also notes another brother of William named Joseph (who was at Ballarat in January 1860).

Other children were born to the Browns in years to come (4), and although it is not known when she arrived, William’s mother Mary also came to live in Australia; her death notice in early September 1872 (5) noted that she was at her son’s residence in Errard Street Ballarat, and also notes another brother of William named Joseph (who was at Ballarat in January 1860).

First year – Magpie Gully

Having arrived, Brown is not visible in the public record until around September of 1855, when he is mentioned at Ballarat with the phrase “whose experience is sufficient guarantee for its able fulfilment.” Clearly Mr. Brown had been active during the past year to develop some kind of reputation. A reminiscence, written in 1869 by George Truscott, recalls the start of the gold rush at Magpie Gully (6):

"… October, with August and September 1855, those were months that the great rush did take place at those gullies ......whilst in October or November at Magpie, Mr W.M. Brown opened a theatre adjoining the Empire hotel, of which Mr Geo. Hathorne and the well-known Dutch Harry were landlords, at which place poor Sherecroff (10) , if I recollect aright, assumed the leading character. Besides this theatre, there were two or three large concert-halls. The main road at Magpie was in a crowded state; proprietors of hotels were taking large sums of money daily, as much as £70 or £100. These facts I can prove, as I was a landlord of one of them myself."

In mentioning that Brown’s theatre at Magpie Gully was ‘adjoining’ the Empire Hotel, Truscott probably indicates that it was, like others of the time, an ante-room to the hotel itself, and possibly not much more than an open room with benches and possibly a raised platform.

In 1873 (7) a pioneer wrote their recollections of Magpie Gully circa 1855, working as a scenic artist for Lola Montez:- “To return — we reached Magpie Gully early in the evening, four or five miles from Ballarat, and near the township now called Sebastopol. Seeing a placard announcing Joe Rave or, the juvenile tragedian, as Hamlet, that night, in a canvas theatre, with a powerful cast, W. M. Brown, I remember, being the ghost, first actor, and first grave-digger, I resolved to stay and witness the production of one of the nefarious and inspired deer-stalker's best plays.

My most vivid recollection of the performance consists in the fact that the juvenile tragedian was at least five and forty, and that for Yorick's skull he held in his hand an unskinned and recently decapitated sheep's head. When he came down to the footlights, endeavoring as much as possible to conceal his burthen, and commenced, "Alas! poor Yorick, I knew him well, Horatio — an infuriated stickler for the niceties of Thespis shouted out, "It's a lie, boys, it's not Yorick, it's a ‘Jimmy!’ "

The roar which followed this announcement, stopped the action of the play for a considerable length of time — the tragedian meantime holding infuriated recriminative dialogue with the first grave-digger — finally he indignantly flung his gory prop into Ophelia's grave, to the intense delight of the hairy, unwashed audience.”

The roar which followed this announcement, stopped the action of the play for a considerable length of time — the tragedian meantime holding infuriated recriminative dialogue with the first grave-digger — finally he indignantly flung his gory prop into Ophelia's grave, to the intense delight of the hairy, unwashed audience.”

Magpie Gully (now just ‘Magpie’) had become a new gold-rush centre in August 1855; just one of many “gullies” in the region, with miners discovering nuggets as much as twelve pounds in weight. (7a) It was a little south of Ballarat and Sebastopol, the two most developed townships. The constant ebb and flow of the population and infrastructure of the region, as gold miners chased the current high-yield areas, was a feature of the time, and the Ballarat area was not just booming, it was exploding with new finds.

The hotels and ‘theatres’ at the Gully might be thought to be rudimentary structures (16) , and indeed some of the earliest venues around the gold fields were not much more than tents; but when the Empire Hotel was put up for sale in 1856 (8) it had two parlours, a dining room, billiards room, five bedrooms, a kitchen and stables. The rapid influx of money, and the demand from the miners for some evening release after their physical labour, led to a surge of drinking and entertainment, gambling, horse racing, prize fighting and cock fighting. In the provincial areas such as Geelong, Beechworth and Ballarat, infrastructure was developing at an astonishing pace, such that a humble tent or rude wooden building in the early 1850s would, by the end of that decade, be supplanted by a far more permanent structure, or even a brick building. Brown’s involvement in the community’s life was right in the middle of the most transformational years of Ballarat theatre.

The writings of actor Joseph Gardiner (9), speak of his arrival at Geelong in 1851:-

“I arrived there, as per engagement, and went straight from the boat to the theatre - that is, it had the name theatre painted on the front; otherwise the structure more resembled an auction mart or lumber repository. The inside was of the most primitive construction - pit unboarded, stakes driven into the earth, and rough slabs nail on for seats .... such a place to be called a theatre was never more falsified by the name.”

“I arrived there, as per engagement, and went straight from the boat to the theatre - that is, it had the name theatre painted on the front; otherwise the structure more resembled an auction mart or lumber repository. The inside was of the most primitive construction - pit unboarded, stakes driven into the earth, and rough slabs nail on for seats .... such a place to be called a theatre was never more falsified by the name.”

What more natural than that Brown should have been drawn to this place and started his life in Australia, by organising entertainments on the goldfield, and creating himself a reputation for getting things done.

Ballarat Business

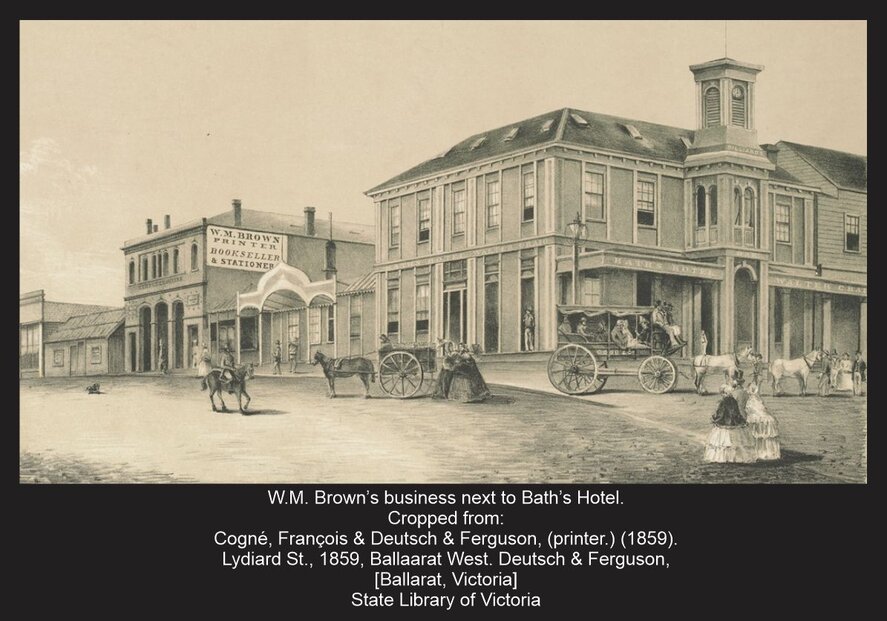

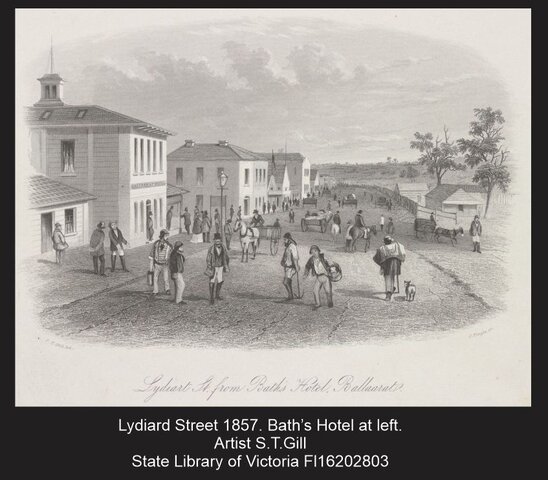

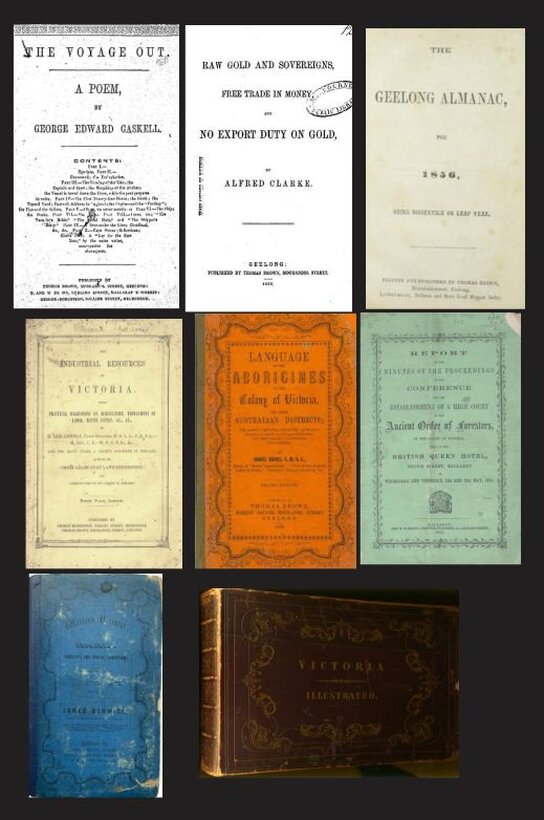

By late 1855 William Brown was probably resident in Ballarat and, though his first business dealings are not clear, it is likely that he started as a stationer cum bookseller, on similar lines to his brother Thomas in Geelong (13). By September 1856 the brothers had become partners, each at their own towns, and were known as “T. and W. Brown, Stationers”. William advertised originally as being located next to the Post Office (at Armstrong and Mair Streets), but his later business, from March 1858, was in the Temple Chambers in Lydiard Street South, next to Bath’s Hotel (which still exists as Craig’s Royal Hotel). The brothers retailed all the necessary papers, pens and other accessories of the stationers’ trade, and stocked the latest books. Thomas was also a printer and his name appears on a number of routine publications of the day, which are detailed at the end of this essay.

There were also several books of considerable historical importance, for which the Browns were publishers,

or co-publishers with Melbourne firms:

- Language of the Aborigines of the Colony of Victoria and other Australian Districts by Daniel Bunce, pub. Thomas Brown - second edition was 1859.

or co-publishers with Melbourne firms:

- Language of the Aborigines of the Colony of Victoria and other Australian Districts by Daniel Bunce, pub. Thomas Brown - second edition was 1859.

- Twenty three years wanderings in the Australias and Tasmania, including travels with Dr. Leichhardt in north and tropical Australia by Daniel Bunce, pub.Thomas Brown, 1857 [also pub. J.T.Hendy, Melbourne].

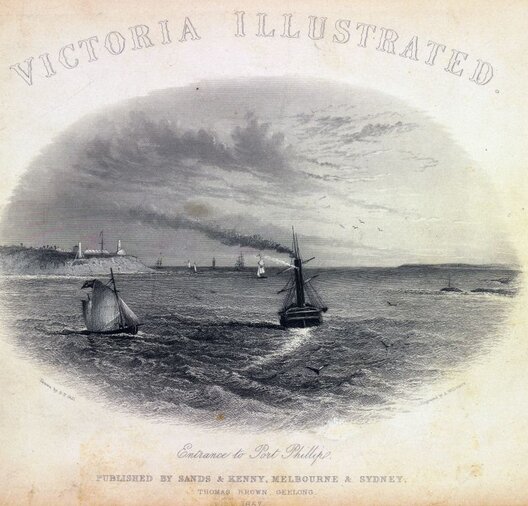

- Victoria Illustrated by S.T.Gill, pub. Sands & Kenny Melbourne, and Thomas Brown Geelong, 1857. The artist Samuel Thomas Gill created some of the most iconic illustrations of early colonial life.

- Western Victoria/Its Geography, Geology and Social Condition by James Bonwick, pub. Thomas Brown Geelong, George Robertson Melbourne and W.M.Brown Ballaarat, 1858 (14)

- Coxon’s Comic Songster, printed and published by W.M.Brown late T. & W. Brown, 1859. This book of humorous and topical song lyrics is, to this day, used by performers of historic colonial songs. (15) Ballarat, at the end of 1854, was living in tumultuous times. The first purpose-built theatre there, the Queen’s Theatre (opened November 1852 as a rudimentary playhouse of calico and rough-hewn timber), was closed in December 1854. The Theatre Royal on Main Road, again a canvas and timber establishment, was offered for sale in April but may not have sold. A concert hall went up in flames as Bentley’s Hotel was torched in October by an angry mob. In December a landmark moment in Australia’s history occurred. The famed Eureka Rebellion took place at Ballarat, miners standing up against harassment by police and demanding a say in making the laws they were called to obey – including taxation with full representation. By April 1855 it appears that only the Adelphi remained in operation at Ballarat.

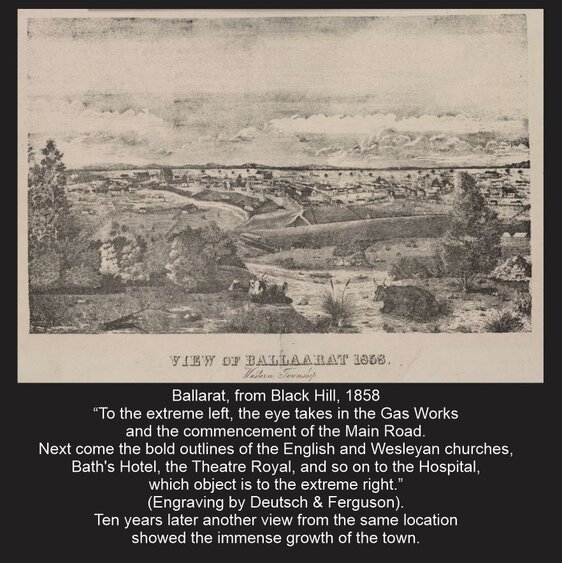

Ballarat, at the end of 1854, was living in tumultuous times. The first purpose-built theatre there, the Queen’s Theatre (opened November 1852 as a rudimentary playhouse of calico and rough-hewn timber), was closed in December 1854. The Theatre Royal on Main Road, again a canvas and timber establishment, was offered for sale in April but may not have sold. A concert hall went up in flames as Bentley’s Hotel was torched in October by an angry mob. In December a landmark moment in Australia’s history occurred. The famed Eureka Rebellion took place at Ballarat, miners standing up against harassment by police and demanding a say in making the laws they were called to obey – including taxation with full representation. By April 1855 it appears that only the Adelphi remained in operation at Ballarat.Into this exciting environment came the Wizard Joseph Jacobs, starting as the opening attraction of the “Royal Montezuma Theatre” on August 13, 1855. The Montezuma was a considerable improvement over previous structures, which the press described as a “splendid new building” of some elegance and well fitted-out interior, though it had been constructed in a mere fortnight. Jacobs initially announced only a short season, but played to crowded houses until at least mid-September, and The Argus (17) said, “great credit is due to him for having provided such an unexceptionable and respectable place of amusement as the Montezuma now presents; smoking and other objectionable proceedings are entirely and effectively prohibited … no doubt a brilliant tour awaits the Wizard Jacobs throughout the colonies.” Indeed, Jacobs was the most famous touring magician of the period. He visited other areas around Ballarat, but famously was back at the United States Hotel in the town when it caught fire in early December, forcing him to jump for his life out a window. (18) The recently rebuilt Adelphi Theatre, where he had been performing with his younger brother assisting as “Sprightly”, was among some fifty or more buildings destroyed, and with it all of Jacobs’ magic apparatus. For a first-hand telling of this story, and a fascinating glimpse into Ballarat theatre at the time, see the Jacobs link.

William Brown enters the Ballarat township’s theatre scene for the first time in September 1855, when an amateur performance was announced, to be given by the members of the newly-founded Ballarat Literary and Dramatic Society, at the Arcade Rooms of the Golden Fleece Hotel, which was on the west side of town, away from the bustling Eastern side. For the Dramatic Society, Brown acted as stage manager (effectively the company manager) , “whose experience is sufficient guarantee for its able fulfilment”, in Dion Boucicault’s “London Assurance” followed by a vocal and instrumental concert.

Whether or not Brown was the sole founding member of the Society, he was certainly the driving force behind its couple of years in existence, and consciously pioneered one of the earliest stable pools of performers in the town, as opposed to the many transient “stars” who would tour for as long as they could pick up the miners’ gold. “In making the above announcement” the advertisement for their performance read, ”the committee trust that the importance of the object will be duly considered by all classes of the community, but more especially by the mining portion of the population, to whom the establishment of such an institution must be of the greatest consequence, and in calling for support, on this occasion, (being the first of a series of performances) the society in return pledge themselves, to spare neither the requisite expense, time, or trouble, to render the entertainments superior to anything that has previously been attempted in Ballarat.” (19)

Following the disastrous fire in December, the Society announced a grand amateur entertainment to raise funds for the relief of the citizens affected. By May of 1856 they were performing in aid of fund-raising for a proposed Mechanics’ Institute, which would itself became a major force in theatrical life. They continued to perform on behalf of charitable causes, and in August they opened at the Montezuma with an amateur production of Brown’s adapted drama, The Will and the Way, to a crowded house noted as “the most respectable that ever assembled within the walls of the Montezuma Theatre … a melodrama of a high order, and … reflects the highest credit upon Mr. Brown and the members of the Literary and Dramatic Society of Ballarat who took the various characters.” (20) As a quality performance, the Star newspaper implied that only the novelty of the occasion made it worthy of notice, but “the various events, characters and tableaux, were brought out and sustained with more minuteness, success, and point, than we were prepared to see at the Montezuma for many days to come.”

Brown was meantime settling into business as a Stationer, but was involved with an important push for a new theatre in Ballarat, as will be seen. In December 1856 (21) he was advertising perhaps the most important publication under the “Thomas Brown” name (with Sands and Kenny, Melbourne and Sydney) – “Victoria Illustrated” containing fifty steel-engraved views of Ballarat, Melbourne, Geelong and other Victorian regions, from drawings by the prolific colonial artist, Samuel Thomas Gill. A second series was issued in 1862 by Sands and Kenny, and the combined editions were published by the State Library of Victoria in 1971 and Lansdowne Press in 1983; which is fortunate since the original edition now sells for thousands of dollars.

Brown also acted as a ticket agent for the town’s theatres and was also becoming involved in town politics, speaking out against an altered location for the new Market Place to Sturt Street, which was known to contain gold and would therefore “take the bread and butter out of the mouths of people who had speculated their money upon understanding that the Market-Place was to be in the portion originally decided upon (Mair Street). A “Mr Brown” who might be our subject, was also vigorously involved in campaigning for the area of East Ballarat to be surveyed with the aim of encouraging storekeepers to build more permanent structures along Main Road.

Brown the Professional

As a dramatist and theatrical from the old country, William Brown distinctly saw himself as a professional of the theatre, despite being only in his twenties. Others, perhaps, perceived him slightly differently. When, in February 1857 he appeared on stage at the Montezuma Theatre alongside Mr McKean Buchanan in School for Scandal, the Star referred to him as “a gentleman amateur” – and yet it praised Brown’s performance above Buchanan’s, saying that the American actor “doubtless flattered himself that he achieved another triumph.” Of Mr. Brown as Sir Peter Teazle, the review noted “an originality, an adherence to nature, and a keen appreciation of the author … as to call forth the marked applause and delight of the spectators.” (22) Clearly he was also busying himself as a dramatist, as in May it was announced that he would produce several of his pieces, including Will and the Way at the Charlie Napier theatre. Advertising mentioned Brown as the author of Green Hills of the Far West and Minnie Grey and possibly Obi, or Three-fingered Jack though this was listed only as “from an original manuscript in the possession of Mr. William Brown”.Will and the Way (or, The Vision of Death) opened on May 23, 1857 under Brown’s directorship and “supported by the best company in the Colonies” at the Charlie Napier Theatre. It ran successfully for at least five nights. The “Charlie” was another example of an early theatre, connected to the Charlie Napier Hotel (1854), which began life as a popular concert hall in 1855, with nothing more than a raised platform and rudimentary side wings. By 1856 the proprietor built a new theatre at the back, a far more robust building with raised boxes, a ‘handsome stage’ and the first gas lighting in Ballarat. Firmly established as a popular theatre, by November 1856 it was featuring Shakespearian plays starring Mr Henry Sedley.

That new theatre lasted until 1861, when it suffered a common theatrical fate; it burned to the ground, but was then rebuilt in brick, and survived as a firm favourite until demolition in 1880. Today a reconstruction of the hotel and upstairs Lodge/Concert room of the Napier can be visited at Sovereign Hill, Ballarat’s historical re-creation of the early township. At the same place, an excellent reconstruction of the Victoria Theatre hosts performances of period works. (23)

That new theatre lasted until 1861, when it suffered a common theatrical fate; it burned to the ground, but was then rebuilt in brick, and survived as a firm favourite until demolition in 1880. Today a reconstruction of the hotel and upstairs Lodge/Concert room of the Napier can be visited at Sovereign Hill, Ballarat’s historical re-creation of the early township. At the same place, an excellent reconstruction of the Victoria Theatre hosts performances of period works. (23)

On May 30, Brown’s piece The Green Hills of the Far West, or the Falls of Niagara was performed; then “Three Fingered Jack” and June 5 saw a final night of “Will”. On June 6 the Napier was ‘crowded to excess’ to witness Brown’s work Minnie Grey, or, The Gypsies of Dingley Dell (another dramatisation of a story, “Minniegrey” by J.F. Smith), complete with a superb moonlight effect, the entrance of the Duke of Wellington, and a grand military tableau. Brown then appeared, June 11, on stage as Jacques Sincere in a standard drama titled “Honesty is the Best Policy”, and as John Box in the well-worked farce, “Box and Cox”. It might also be noted that on June 12 the advertising for the show included a promotion for a June 18 featuring “Mysterious! Mysterious! Sceptics Beware!!! Rappings and Table Movings.”

Many years later, an anonymous “Australian Actor” wrote, in a recollection of Brown, “His most successful effort was ‘The Will and the Way’ which was produced at the Victoria Theatre [the 1859 production, presumably] … it proved to be a piece of sterling work, and met with marked success. Brown was a slow, dilatory, careless man; and I think he told me he had never had it printed or protected, and so I presume if a copy were sold to a manager, the laborious method of hand-copying would have to be resorted to (typewriters were not dreamt of then). Managers would not give much for a colonial made article, and so the author got little else but kudos for his labour. I don’t suppose there are more than three manuscripts of Brown’s play in existence; and one of them, I think, is in possession of Mr. Edmund Holloway , for I remember him staging it some years ago.”

The writer may be correct that the numerous productions of Brown’s play did not bring him much money. Appropriation or outright theft was commonplace in relation to theatrical productions, and authors had little protection; but then, Brown had not created the original story either. It seems curious, also, that someone who worked as a printer would not have taken the time to set and print his own work. The characterisation of Brown as slow, dilatory and careless does not seem to fit his vigorous theatrical activities across the years. (The same article refers to Mr. Brown’s talents as an actor, which we will look at later).

It is clear that, with these plays to his credit, William reserved to himself some dignity as a professional; which would account for his refusal to perform in the announced farce, “The Windmill” in August 1857, as his name had not been sufficiently displayed in large type in the house bills. He did, however, perform in a farce in a benefit for the local Servant’s Home, and was supportive of the amateur Literary and Dramatic Society, taking on a role as Mr Coddle in Buckstone’s comedy, Legion of Honour at the Montezuma theatre.

His appearance was complimented in the press:- “Mr W.M. Brown appeared to great advantage; he played the part of Mr. Coddle admirably and was well supported by the ladies of the company”… “Mr.Brown’s talent as an actor was quite sufficient to draw a good house, independent of the cause”… “Mr. Brown, as Coddle, was the ruling genius of the piece, and he certainly kept the interest well alive from beginning to end.” (25)

His appearance was complimented in the press:- “Mr W.M. Brown appeared to great advantage; he played the part of Mr. Coddle admirably and was well supported by the ladies of the company”… “Mr.Brown’s talent as an actor was quite sufficient to draw a good house, independent of the cause”… “Mr. Brown, as Coddle, was the ruling genius of the piece, and he certainly kept the interest well alive from beginning to end.” (25)

This performance was intended to raise funds for delegates to the Land Convention, an important and activist campaign for land reform in opposition to the “squatters”, under the slogan “A Vote, a Rifle and a Farm”. Although well attended, the other expenses of presenting the show meant that little profit was seen; and a local digger took exception to William Brown’s involvement (26):

THE AMATEUR BENEFIT FOR THE CONVENTION (?).

(To the Editor of the Star.)

Sir, It is with great regret that I have heard that the efforts of that talented society, the " Literary and Dramatic," have not been crowned with the success they merit. All who were the delighted spectators of these amateurs' excellent acting at the Montezuma on Tuesday night, must have been struck with the repletion of the house, and must have anticipated that a good round sum would be added to the funds of the Convention Delegates. I now hear that the net balance to be paid over is less than thirty shillings. As a digger, and having taken some trouble to patronize the performance (self and family), I have some right to know on whom the blame should fall, and so hope the society will publish an account.

It has been whispered abroad that one of the society, an actor distinguished both as a professional and as an amateur, charged £10 for his, in all senses, valuable services on the occasion. I trust that this may prove a falsehood.

Your obedient servant, LOSSIFIT. Ballarat, August 21.

(To the Editor of the Star.)

Sir, It is with great regret that I have heard that the efforts of that talented society, the " Literary and Dramatic," have not been crowned with the success they merit. All who were the delighted spectators of these amateurs' excellent acting at the Montezuma on Tuesday night, must have been struck with the repletion of the house, and must have anticipated that a good round sum would be added to the funds of the Convention Delegates. I now hear that the net balance to be paid over is less than thirty shillings. As a digger, and having taken some trouble to patronize the performance (self and family), I have some right to know on whom the blame should fall, and so hope the society will publish an account.

It has been whispered abroad that one of the society, an actor distinguished both as a professional and as an amateur, charged £10 for his, in all senses, valuable services on the occasion. I trust that this may prove a falsehood.

Your obedient servant, LOSSIFIT. Ballarat, August 21.

Brown’s response on August 26:

THE BENEFIT FOR THE CONVENTION.

(To the Editor of the Star.)

SIR, - I saw an article in your Saturday's issue, supposed to have been written by a digger with a large family (as it states). I think the letter was uncalled for, and a vain attempt to put a slur upon my character, by some piqued or jealous individual; perhaps, therefore, you will oblige me by inserting the following plain statement.

SIR, - I saw an article in your Saturday's issue, supposed to have been written by a digger with a large family (as it states). I think the letter was uncalled for, and a vain attempt to put a slur upon my character, by some piqued or jealous individual; perhaps, therefore, you will oblige me by inserting the following plain statement.

I am not an amateur - if fifteen years’ experience is sufficient proof - nor did I ever appear as one in Ballarat. I was the stage Manager of the Literary and Dramatic Society, and as such I was always announced to the public. I gave my services to the society gratuitously, because the object of it was to play for charitable and public purposes ; but I soon found that the various committees under whose auspices we played, were apathetic, and did little or nothing, as in the late instance of the Land Convention. Consequently as nothing can come of nothing, some of the performances were a loss to the amateurs and myself, and unprofitable to the object for which they played.

On the occasion of the late performance, the amateurs offered me ten pounds for my services, in directing their pieces and playing and studying two long parts in "Married Life" and the "British Legion." The committee of the Convention never requested my services to play, or I could have given them, but certainly not have given them the time it occupied in directing and producing the pieces selected. I do not think any portion of the public could reasonably expect me to waste my time (which is to me, like everybody else's, money) without proper remuneration. The letter states he believed I charged ten pounds for my services, and hopes this may prove false. I cannot understand why he should hope my services were not worth ten pounds, when, in a late engagement at the "Charlie Napier," I received £236 for three weeks. [Presumably referring to his plays produced in May/June].

Now for the point at issue. I did not receive ten pounds: because, when I found the expenses were heavy (although, I believe, under the expenses of any other amateur performance in Ballarat) I made them a present of five pounds: the other five pounds I have not as yet received - nor will I now accept it. Still, ten pounds is honestly due to me; and is for the Convention and amateurs to decide who owes it to me, or whether the ten pounds were charged by me or offered to me. The following is a correct statement of the Receipts and Expenses, which no one has thought proper to publish, and with which I certainly have nothing to do; my duty being only to direct the performance, But to satisfy public curiosity I insert, (with the Editors permission):- [a full list of receipts and expenses was printed]

I must apologise for wasting your valuable space, but as self preservation is the first law of nature, I could not allow the letter to pass unanswered. For the future I shall dissolve all connection with amateur performances, since my services command such undeserved censure ; and when I again spare time from my business to appear before the public, it shall be in a professional capacity, when I hope to receive more satisfactory emolument. With many thanks for this insertion.

I am, Sir, Your obedient servant,

WILLIAM M. BROWN. Lydiard-street, Ballarat, August 25th. 1857.

I must apologise for wasting your valuable space, but as self preservation is the first law of nature, I could not allow the letter to pass unanswered. For the future I shall dissolve all connection with amateur performances, since my services command such undeserved censure ; and when I again spare time from my business to appear before the public, it shall be in a professional capacity, when I hope to receive more satisfactory emolument. With many thanks for this insertion.

I am, Sir, Your obedient servant,

WILLIAM M. BROWN. Lydiard-street, Ballarat, August 25th. 1857.

From this time, the Literary and Dramatic Society subsided into inactivity, save for a half-hearted attempt to revive it. The only other theatrical team in Ballarat was made up of members of the Garrick Club, who presented a number of plays in the late 1850s. It might be reasonable to think that Mr. Brown’s leadership had been the driving force.

His close involvement with the Montezuma and Charlie Napier theatres continued into September, with his engagement to perform at the Montezuma in The Bohemians of Paris, initially announced for twelve nights from September 7, though the season did not last that long. As well, Brown performed on the 10th in the drama The Last Man; or, the Miser of Eltham Green, with Brown as the miser.

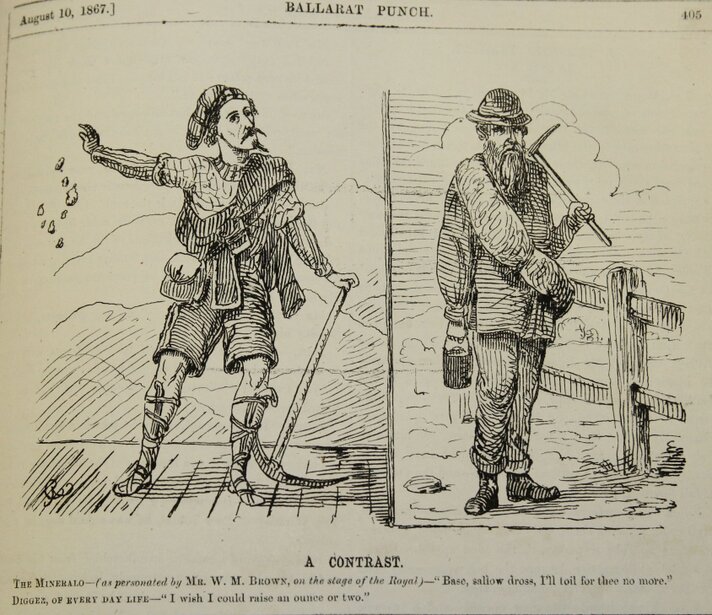

On September 13, also at the Montezuma, the press announced “Mr W.M. Brown’s new piece”. It is unclear which of the plays was written by Brown: Simon Lee, or, the Murder at the Five Field Copse, or the drama Luke the Laborer, in which Brown performed in the title role. Without throwing much more light on whether William Brown was the author or performer of “Simon Lee”, the Star subjected the storyline of that drama to a lengthy and scathingly satirical half-page of text on September 14, in the guise of a mock court-room trial of “W.M. Brown, before Melbourne Punch Esq. S.M and Good Taste Esq. J.P.” …. A gentleman from whose intelligent appearance better things might have been expected, was charged with uttering and selling sundry illegitimate wares at the Montezuma during the week last past; there was a second count against him for utterly selling the public … the Protector of Common Sense had seen ‘Simon Lee.’ He considered that the progress of that melodrama was a wantonly hostile march into the bowels of his domain, and the sooner some effectual impediment was thrown in its way, the better … the Inspector of Theatrical Nuisances …. considered it a violent nuisance committed in the very nostrils of the public.” In other words, ‘Simon Lee’ was a stinker!

Theatre Royal, Ballarat

To examine William Maxwell Brown’s connection to one of the most important theatrical developments in Ballarat, we need to revert back to late 1856. As Ballarat grew, and settled into a township of more stability than its former volatile gold-fields existence, the Eastern section where most of the theatres had been built was becoming less attractive as a permanent location. Not only was the area considered somewhat disreputable, there was a serious risk of falling into a miner’s hole on a dark night; and the theatres themselves were always at risk of being “rushed” and demolished if it was suspected that they were sitting on top of a gold deposit. The Montezuma Theatre was sitting almost next door to a mining claim (27). Gold mining was still strong, but the feverish peak of the Ballarat rush had subsided by 1856.The Star, of November 11, 1856, made its first announcement concerning plans for a new theatre:

“Advance Ballarat” – We understand that the enterprising proprietors of the Montezuma have just made arrangements for the erection of a theatre upon a scale of magnificence, alike in extent and decoration, hitherto unknown on the gold-fields. We hear that contracts are about to be taken, if not already accepted for building a theatre capable of accommodating as large an audience as that which sometimes has been gathered together in the Theatre Royal Melbourne. The plan of the new building will, we believe, be also after that of the Bourke Street house; the present Montezuma being altered so as to form a kind of vestibule to the new theatre about to be erected behind. A gentleman of considerable experience in theatrical management, and well known amongst the play-going folk everywhere in Australia will be concerned in the new arrangements now in the tapis; and we can assure our readers that in the matter of dramatic entertainments we are likely to attain as proud a position as we have so long held in connection with the mining interests of the colony.”

“Advance Ballarat” – We understand that the enterprising proprietors of the Montezuma have just made arrangements for the erection of a theatre upon a scale of magnificence, alike in extent and decoration, hitherto unknown on the gold-fields. We hear that contracts are about to be taken, if not already accepted for building a theatre capable of accommodating as large an audience as that which sometimes has been gathered together in the Theatre Royal Melbourne. The plan of the new building will, we believe, be also after that of the Bourke Street house; the present Montezuma being altered so as to form a kind of vestibule to the new theatre about to be erected behind. A gentleman of considerable experience in theatrical management, and well known amongst the play-going folk everywhere in Australia will be concerned in the new arrangements now in the tapis; and we can assure our readers that in the matter of dramatic entertainments we are likely to attain as proud a position as we have so long held in connection with the mining interests of the colony.”

As with many early plans, intentions to build the new theatre behind the Montezuma were changed the following year. (The Montezuma was located on Main Road and Eureka Street, and ultimately burned down in 1861.) Whether the mooted “gentleman of considerable experience in theatrical management” was George Coppin, or possibly G.V.Brooke, or William Hoskins is not clear at this stage, but both Brooke and Hoskins would enter the scene later on.

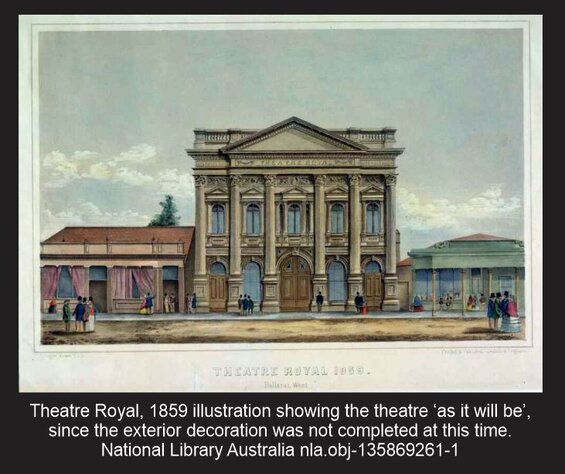

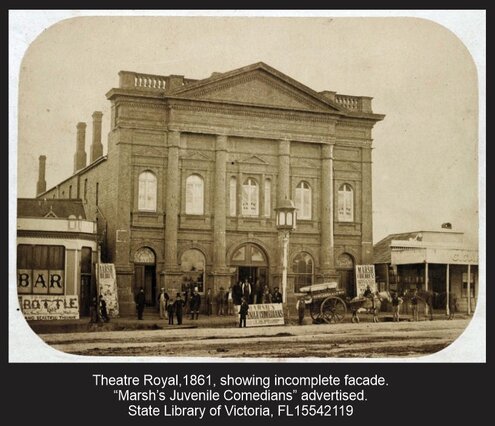

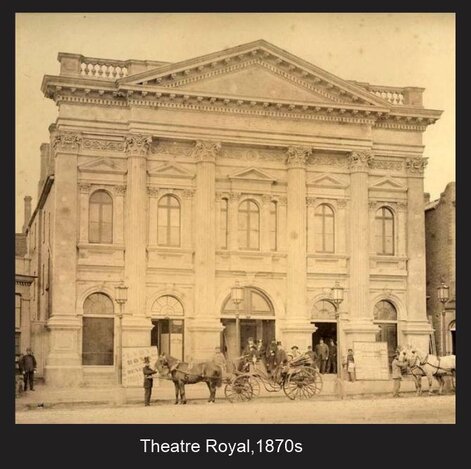

The new theatre was to be named the Theatre Royal, and it became the first permanent theatre built in inland Australia. Its chequered history and ultimate demise in 1878 have been extensively documented by Ailsa Brackley du Bois, ‘Repairing the Disjointed Narrative of Ballarat’s Theatre Royal’ – see note (28), but our focus is on the earliest days leading up to its opening , and its first financial hurdles, because a major player in these early days was William Maxwell Brown.

Oddly, there had been a “Theatre Royal” on the Ballarat Flat back in early 1854, capable of holding 600 people, a 20x15 foot stage, with boxes, a bar and green baize drop curtain. “Newly erected regardless of expense” it seems to have no sooner gone up than it was advertised for sale (29) and was heard of no more.

The Ballarat Theatre Royal Committee was formed, under the Chair Mr. J. Knight, and by September of 1857 the decision had been made to site the new theatre on a block of land in the more suitable Western section of town, next to the Clare Hotel in Sturt Street (next to modern-day Myer). The land had been purchased and shares were already being taken up; Mr. Brown was one of those authorised to sell shares. By October, (30), plans were on display at architect Backhouse & Reynolds, and building tenders were being let.

Foundation Laying -

Foundation Laying -On January 20, 1858, the foundation stone was laid. The celebrity guest was Gustavus Vaughan Brooke (1818-1866), the Irish tragedian, and a partner with George Coppin; he is regarded as having done some of his best work during the six years he performed in Australia but, while heading back to Australia from England in 1866, he would perish in a storm which sank his ship.

Although Brown was mentioned in the press as ‘Vice-Chair’ of the committee, he was prominent in proceedings and most likely was the Chairman; certainly in later months he was noted as the Chair.

Mr W. M. Brown proceeded to address the assembly :-" Ladies and gentlemen, as one of a small board of directors connected with the erection of the Theatre Royal, Ballarat, I have much pleasure in requesting that most eminent, popular, and highly gifted gentleman, Mr Brooke, to lay the foundation stone. The scroll which is to be placed in the bottle is to the following effect, and I will now read it:

COLONY OF VICTORIA.

Wednesday, January 20th, ISSB.COLONY OF VICTORIA.

Theatre Royal, Ballarat.

This is to certify that the foundation stone was duly placed herein on the above date, by GUSTAVUS VASA BROOKE, ESQ.

Directors—

W. M. Brown, Esq.

James Bouchier

Gilbert Duncan

Joseph Backhouse

Robt. McNiece

Thomas Wymond

James Nichol

Robert Underwood.

James Wright

Backhouse and Reynolds, Architects.

Mr Brown addressed Mr Brooke: "The next duty which devolves upon me is to present you with the humble instrument for laying the foundation stone. I feel convinced that not only the Board of Directors and the members of the theatrical profession, but the commercial community and the public in general, join in expressing the pleasure of presenting you this testimony.''

Mr Browne then presented Mr Brooke with the trowel, who, in reply, said, "I have great pleasure in accepting this trowel. I feel honoured by the office you have allotted to me, and will endeavour to do my duty as well as I possibly can."

The bottle containing the scroll, coins and newspapers were then placed in the hollow of tile stone, Mr Brown observing that it contained a lasting memento of the greatness of Ballarat in erecting such a theatre, and when that theatre had ceased to exist a greater one would no doubt arise in its place.

The stone was then lowered. Mr Brooke having applied the plummet and the level, then struck it three times with a mallet and said "I now declare this stone to be well and truly laid."

Mr Brooke’s speech:

“LADIES AND GENTLEMEN,—Among the many proud and happy moments I have known since first I landed on these shores, I beg you to believe that I shall evermore rank the present as one of the proudest and happiest. This is the second time that I have had the gratification of laying the foundation stone of a temple dedicated to the drama in Victoria, and I hope that the progress that will be made with this edifice, and the success it will achieve, will be as striking as that which signalised the erection of Coppin's Olympic, at Melbourne, only six weeks having elapsed between the day on which I deposited the first stone and the period at which it was opened for the reception of the public. Ladies and gentlemen—one of the most distinguished critics of the present century— I allude to William Hazlitt—has shrewdly remarked that—' The stage is an epitome, a bettered like-ness of the world with the dull part left out. Wherever there is a playhouse (he proceeded to say) the world will not go on amiss. The stage not only refines the manners, but it is the best teacher of morals, for it is the truest and most intelligible picture of life. It stamps the image of virtue on the mind by first softening the rude materials of which it is composed, by a sense of pleasure ; it regulates the passions by giving a loose to the imagination; it points out the selfish and degraded, for our detestation, the amiable and generous to our admiration; it is a source of the greatest enjoyment at the time, and a never failing fund of agreeable reflection afterwards.'

“For these reasons, ladies and gentlemen, I rejoice to take part in the proceedings of this day, and I look forward with pride and pleasure to the verdict which posterity will pronounce on the consummation of the work we are initiating. ' There' they will say, ' even in the primitive days of the colony, lived a people of marvellous energy and indomitable enterprise—men who shrunk from no toil, and were disheartened by no difficulty. Yet, while they were strenuously laboring to lay broad and deep the foundations of a great empire, they did not forget the cultivation of those arts which shed a charm o'er life, impart a grace to society, communicate an impulse to civilisation, and strengthen the bonds of human brotherhood. To these ends, then, we found and dedicate this edifice, and for long years to come may it be thronged nightly with happy Ballaratians, and may those who tread its boards be worthy of their high vocation, and minister successfully to the entertainment and instruction of those who admire and uphold the drama. With these few remarks I shall conclude. I have much pleasure in having laid the foundation stone of the first theatre ever erected on the township of Ballarat, and from this foundation may there be raised a superstructure perfect in all its parts, and honorable to the builder. (Loud cheers.)"

Mr Brown said, although not possessed of the talent of the gifted gentleman who had last addressed them, nevertheless he felt particular pleasure in giving the meeting an account of the arduous task the Board of directors had undertaken, and of the proceedings of the Committee of the Theatre from its formation up to the present time. Generally speaking, there was a prejudice against theatrical speculations, as being bad and not paying. It, however, turned out in most cases, that shareholders in a theatre paid their rent and had something left in the till. The theatre, it was expected, would cost about £8,000, and the shareholders need not be frightened, as they would be subjected to no liability beyond the amount of their shares. The shareholders amply protected by the deed, which had been most carefully drawn, and which any of them could see at Mr Randall's office.

It had been determined to raise the amount of capital to £10,000, although the architect still adhered to their former opinion that the building would only cost £8,000. This sum could be raised by 500 shares of £20 each. Underneath the theatre there were two shops, which could be let for £8 a week, then there were four bars which could be let for £5 a week each, thus making £28 a week.

It had been determined to raise the amount of capital to £10,000, although the architect still adhered to their former opinion that the building would only cost £8,000. This sum could be raised by 500 shares of £20 each. Underneath the theatre there were two shops, which could be let for £8 a week, then there were four bars which could be let for £5 a week each, thus making £28 a week.

Again, there were to be 24 bedrooms, kitchen, and elegant dining rooms, and a rental of £6 a week at least might be derived from these, thus making an income of £33 a week. Then again there the theatre itself, which perhaps—although some parties might not think that it was worth much for the purpose of rent, but he differed from them—was worth £20 a week although perhaps, that sum would not be got for it. Again, there was a large, assembly-room or saloon to be attached to the theatre, which could be let for £50 -a rough pound a week. Mr Brown here observed that a return of £2500 a year could be depended upon from the theatre, and the shareholders would realise at least 12½ per cent, if not 25 per cent, for their money. He was not going to say which is Ballarat and which is not, but as the people of the township had patronised the theatres on the Flat, those below might support the theatre on the Township. The prices proposed to be charged were from 1s to 7s 6d, so that every class of the community might be satisfied. It was proposed to have six egresses to the front in order to guard against fire. The plans of the building had been approved of by the best architects in the colony; the scenery, decorations, and in fact all the appointments connected with the theatre, would be of the best description.

Mr Brown then proceeded to state that it required fifty more shareholders to put the roof on the theatre, and fifty more to have the theatre opened in six months. He concluded his speech by calling for three cheers for Mr Brooke, three cheers for Miss Provost, and three cheers for the members of the theatrical profession. This concluded the ceremony.”

While no doubt very busy with planning for the new theatre, Brown found time to appear in a performance of The Will and the Way as the character Old Martin, with Edmund Holloway also in the cast. He also moved into his new premises in Temple Chambers, Lydiard Street, from which he provided printing and bookbinding services, a newspaper reading room, a library of over 4,000 volumes, and a letter writing room. In June, by mutual agreement, the partnership of T. and W. Brown was dissolved, and William was now operating as an independent firm.

Fundraising for the theatre continued, with the aim of raising £10,000 capital to “erect a Theatre in Sturt Street, of such superior character as will afford accommodation to persons of every class. Entertainments of the highest order will be presented, and it is intended to make the building worthy of the best dramatic and operatic talent …. a lasting monument of liberality and enterprise.” (31) The shares may have been selling, but it proved necessary on October 14 to advertise a reminder that the final call for payment on shares was overdue.

Brown was the chairman, with a directorship made up of local shopowners, hotelkeepers and architects. If William did not have enough on his plate, he also put out tenders to erect a small brick cottage in Errard Street for himself.

And then, in September (32) he was involved in a court case. A certain Thomas Jackson, who described himself as a machinist in the employ of the Wizard of the North (John Henry Anderson) at the Charlie Napier Theatre, in what was probably a somewhat drunken state, decided to interrupt Mr. Brown and make a series of derogatory comments about his past. Apparently he had some familiarity with Brown in his early days in England, and he made some taunting remarks about how another actor (33) had beaten him up on stage; and more rudely, that Brown was not the author of The Will and the Way. After some minutes of back and forth, William Brown struck Jackson several times and (he said) “I am sorry I did not hurt him, but my poncho was in my way.” Ultimately the presiding magistrate had enough of the back and forth in court, and expressed regret that Mr. Brown had responded to a clear provocation, and that Brown was not sorry for his actions. One shilling damages and 2s6d court costs against Brown. Reports of the case in the British paper “The Albion” (Nov.15) state that Brown was “formerly well-known in Liverpool as a theatrical amateur and stationer”.

And then, in September (32) he was involved in a court case. A certain Thomas Jackson, who described himself as a machinist in the employ of the Wizard of the North (John Henry Anderson) at the Charlie Napier Theatre, in what was probably a somewhat drunken state, decided to interrupt Mr. Brown and make a series of derogatory comments about his past. Apparently he had some familiarity with Brown in his early days in England, and he made some taunting remarks about how another actor (33) had beaten him up on stage; and more rudely, that Brown was not the author of The Will and the Way. After some minutes of back and forth, William Brown struck Jackson several times and (he said) “I am sorry I did not hurt him, but my poncho was in my way.” Ultimately the presiding magistrate had enough of the back and forth in court, and expressed regret that Mr. Brown had responded to a clear provocation, and that Brown was not sorry for his actions. One shilling damages and 2s6d court costs against Brown. Reports of the case in the British paper “The Albion” (Nov.15) state that Brown was “formerly well-known in Liverpool as a theatrical amateur and stationer”.

The construction of the Theatre Royal must have been achieved very rapidly. In October the building was advertised for lease, “containing an extensive tier of boxes, large gallery, pit, stalls, &c. and capable of accommodating 1,500 persons …. The hotel will contain a large bar, bar parlor, public parlor, and refectory; billiard, supper and bed rooms; large kitchen and cellar; and an elegant suite of private apartments.” Yet in November tenders were still being requested for the supply of about 350,000 bricks to be used in the construction.

William Brown wrote to the press in November to deny that a version of The Will and the Way , being played in Melbourne, was his adaptation; probably necessary since “Bell’s Life” newspaper described the plays as an “incomprehensible and sanguinary hotch-potch … this abomination.” (34)

Opening of the Theatre Royal

The theatre’s opening was announced for Monday, December 27, 1858, and a manager had been found, along with a company of players.

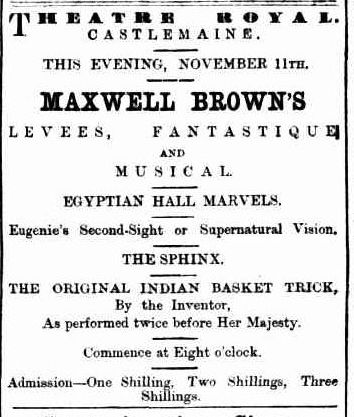

The theatre’s opening was announced for Monday, December 27, 1858, and a manager had been found, along with a company of players. He was Mr. William Hoskins (1816-1886), “late stage manager at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, Olympic &c.”, a native of Derbyshire who had a successful light comedy career in England and was the elocution teacher of a young Henry Irving He had been in Australia since 1856 and would go on to produce a range of Shakespeare, burlesques and dramas at the Royal, before becoming manager of Melbourne’s Theatre Royal and the Haymarket Theatre. He was also a forebear of well-known Australian performer, Barry Creyton. (35)

The ‘Star’ of December 27 gave over some lengthy paragraphs to a physical description of the new theatre, but mentioned, ‘ though for a long time the speculation of the company seemed to languish, through the extraordinary energy of the directors the enterprise has been fairly concluded … ‘It is undoubtedly one of the finest we have in the colony … the building has cost fully £10,000 and its erection is mainly owing to the energy of the directors, Messrs. W.M. Brown (Chairman), Backhouse, T.Wymond, Duncan, Rowlands, R. Underwood and Mr E.C.Moore, Secretary.’

Following the first performance, appropriately titled “Time Works Wonders”, Mr. Hoskins came before the curtains to express his ambitions to provide the best entertainment in his power, and to further the social growth of Ballarat via the “healthful moral culture” of the theatre. “Few of you are aware of the difficulties that have beset the directors, even from the outset of their labors”, said Hoskins, “and I feel I should not be doing them justice did I not call your attention to the fact that, to the untiring energy of the architect, and the professional acumen of my old fellow laborer, Mr. W.M. Brown, in the vineyard of the muses, with the hearty co-operation of a few others of the Board, you are indebted for this magnificent theatre, which I trust may long stand an ornament to their indomitable energy … let me hope that the prosperity of our little temple may go hand-in-hand with the increasing prosperity of Ballarat … we have here a temple worthy of its service.”

The Theatre Royal was built in a robust surge of optimism for the social and cultural future of Ballarat, and it was the first in a series of permanent structures housing the arts. Successful in its first couple of years, it would soon engage in a competitive struggle with the Mechanics’ Institute (28) , and battle through a series of ups and downs before being overtaken by other theatres. William Brown would have more involvement with the operation of the Theatre Royal, and it would be his first downfall.

1859 – Purchase of the Royal

The year 1859 was to become a challenging one for Brown, although to some extent we must read between the lines to understand what was happening. January started badly, with a small fire breaking out in a room near the stage, where combustible supplies for the theatre’s pyrotechnic effects were kept; fortunately it was quickly extinguished and damage was slight, but the fire again broke out in the afternoon, and the press spoke out against the practice of storing inflammable materials. Never a more prophetic word was printed; fire put an end to any number of Australian theatres, and in January 1861 a massive fire broke out in Ballarat, attributed to this same habit of storing incendiary devices at a theatre.

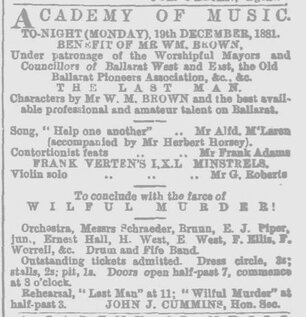

“In consideration of that gentleman’s active and valuable exertions during the erection of the above magnificent building, and his zeal for the advancement of first-class representations on Ballarat”, Mr. Brown was given a complimentary Benefit night on January 20, at which he played roles alongside Mr. Hoskins in both the Vicar of Wakefield and a farce, Brother Ben. The practice of Benefits, whereby the recipient would take the profits of the night, was common not only at the end of a successful run, but also in the event of an actor needing some financial support from the community; and Brown was a beneficiary many times over coming years. In this instance, the Star said, “it is to be inferred, and we believe just so, that the public in great measure owes to him the erection and establishment of so handsome a place of amusement as the Theatre Royal. Apart from his position as a citizen amongst us, Mr. Brown has for some years exhibited a lively interest in theatrical matters on Ballarat, and in the prosperous conclusion to which he has brought the enterprise in question, we see him identified with a portion of the history of the locality.”

Aside from some references during the previous year to the difficulties experienced by the directors in getting the theatre built, there are clues that all was not well at the Ballarat Theatre Royal Company. The Secretary, Edward Moore, resigned and was replaced at the end of January. All seemed well on stage, however, and a variety of plays and dramas was successfully presented to the public, which responded with good attendance in the main, and complimentary reviews in the local newspapers. Shakespeare, it seemed, was not as well received as it might have been, but there was opera, drama, farce and burlesque, organised by Mr. Hoskins who was clearly trying to find the ideal balance of attractions for his clientele. Mr. Brown appeared again in February, in the farce of Poor Pillicoddy, and in March in the role of Joe Bean in The Will and the Way.

February also saw the sale of Temple Chambers, the building in which Brown housed his stationery business. Aside from having a clearance sale of stock, there is no indication that his business was affected, and he was working on the dramatisation of another J.F. Smith story, “Woman and Her Master” which arrived on the Royal stage in early April.

It should be mentioned that during 1859 another ‘Theatre Royal’ was in operation, this being a portable construction at Back Creek. It was a mixed success, the management at one stage eloping with the takings, and constantly under the need to re-locate (buildings were frequently dismantled and literally hauled through the streets to a new site).

Starting on March 23, the Royal Victoria Theatre in Sydney, under the direction of Mr. Samuel Colville, presented The Will and the Way, which the advertising stated was “at present being produced in both Theatres at Ballarat, with the greatest success that has ever attended any production.”

The play had been on stage at the Haymarket in Bendigo in February, featuring the actor Joe Gardiner. In Ballarat it was produced at both the Charlie Napier and Theatre Royal in early March – the Napier production under the management of Mr and Mrs Clarance Holt, who claimed that the play was “W.M. Brown’s wonderful drama of The Will and the Way, the property of Mr Clarance Holt, by virtue of purchase made in England”. Mr Brown would later advertise that he had received, from England, full documentary proof of his authorship of the stage drama, and hitting out at those who either denied him as the author, or presented pirated versions.

The play had been on stage at the Haymarket in Bendigo in February, featuring the actor Joe Gardiner. In Ballarat it was produced at both the Charlie Napier and Theatre Royal in early March – the Napier production under the management of Mr and Mrs Clarance Holt, who claimed that the play was “W.M. Brown’s wonderful drama of The Will and the Way, the property of Mr Clarance Holt, by virtue of purchase made in England”. Mr Brown would later advertise that he had received, from England, full documentary proof of his authorship of the stage drama, and hitting out at those who either denied him as the author, or presented pirated versions.

By June, business affairs at the Theatre Royal were starting to shift. William Hoskins moved into a role as stage manager (effectively controlling the artistic operations) which Brown took over as sole lessee and manager, implying that he would be in charge in the financial dealings. Prices of admission were lowered, and the opening time brought back to the earlier time of 7:30pm – on June 27 it was advised that Messrs Brown and Hoskins would deliver two addresses, ‘to which the attention of the public is respectfully solicited.’

For a new theatre, a few adjustments to operation would not be unusual, but the fact that Brown was the sole lessee might indicate that some difficulties were being experienced in attracting new hirers of the building. A court case was brought on September 5 for payment of £14 in rates due on the Theatre, and on September 19, the Star made some telling commentary that a recent fund-raising performance by the Philharmonic Society had attracted £119 in sales, but resulted in a mere £15 net profit; and the Philharmonic announced that it would present Handel’s Messiah in December, “provided a suitable building can be obtained for the purpose.” In other words, despite the early projection of income, the overheads of operating the theatre were proving more than expected, and profitability was in question.

Mr Hoskins continued to make changes to the style of performance, trying to find the sweet spot between respectable and intellectual drama, and entertainment for “the lovers of fun and frolic”. (36), and later in the year, the local council installed a public urinal in the street near the theatre, after complaints that “the effluvia arising from the nuisances committed by the playgoing portion of the community is at present almost unbearable.” (37)

Brown performed several times at the theatre in Will, Ivanhoe and Othello, where his role as Iago was remarked (38) to be of an overly melodramatic and unsubtle performance; he “carried the gods with him … there were such indubitable symptoms of pure facial and pantomimic travesty as left little room for wonder at the occasionally ferocious delight of the gallery.” His talents as an actor were not in question, but it seems that William Brown was more suited to vigorous drama than nuanced characterisation. The overall production of Othello was felt by the press to be not well-advised, with the talent currently available to Mr Hoskins.

For whatever reason, the Theatre Royal Company was in disarray, despite the apparent success of the shows being presented. On September 22, the theatre and its hotel were advertised for sale the following month, complete with land. It was heavily promoted to Capitalists, Speculators and other as a splendid investment, with emphasis on the theatre which was “for size and beauty, second only to the Theatre Royal, Melbourne … one of the most certain paying speculations in the colony…. extensive and beautiful building which has never failed to elicit from strangers the most unbounded surprise and delight.”

The cause of this sudden and potentially disastrous sale seems to have been the collapse of the Theatre Royal Company, whether due to internal disharmony among the shareholders, or a simple disinclination of the company to be actively involved in the operation of a theatrical business. In early November, meetings were held to wind up the Company, but an adjournment was required, with an advertisement that “shareholders who wish to avoid legal proceedings are requested to attend."

Preparation for the dissolution of the company must have been in the wind for some time prior as, back on October 18, the Theatre Royal was sold at public auction to William Maxwell Brown, who now became the Sole Proprietor at the bargain price of £6,100, an astonishing reduction on a building which had cost some £11,000 only the year before. No suspicion was raised in the press of any untoward dealings, and the inference seems to be that Brown, seeing no potential buyers for the Theatre, had stepped up in a valiant attempt to rescue the infant theatre from collapse.

Bargain or not, £6,100 was no small sum for a single businessman to find. The mortgage for the theatre was now held by a Henry Miller who appears to be the same businessman referred to by the press as “our colonial Shylock” (40). Brown was leaping, boots and all, into the theatrical business, and by the end of November he had sold off his stationery and bookselling business to Evans Brothers, formerly of the Main Road at Ballarat. As an indication that he was not motivated by mercenary considerations, he donated £72 raised at the theatre in a December benefit for the sufferers of a recent fire. (A similar benefit was held at the Charlie Napier the same evening, and in a disgraceful display, firefighters were pelted with objects by some citizens simply because they made a choice to attend the Royal’s concert instead of the Napier).

1860 saw a rapid and calamitous end to William Brown’s apparently hasty decision. He was still in control of the theatre in early January, when it was noted that his rarely-mentioned brother, Joseph, had been fined for blocking Sturt Street with a bullock-team hauling a massive gas holder destined for installation at William’s theatre. On the sixteenth, it was announced that William would take a farewell benefit at the Royal, previous to retiring from theatrical management, and make his last appearance on the stage for a lengthened period, “after which Mr. Brown will deliver an explanatory address." That address, unfortunately, was not detailed in the newspapers.

Messrs. Hoskins and Bellair took over the operation of the Theatre Royal Hotel in February, Hoskins also becoming the sole lessee and manager of the theatre; and on the tenth, Mr. Brown (mentioned as a licensed victualler) assigned the entirety of his real and personal estate (39) to a trustee group made up of William Hoskins, and local businessmen George Munro and Thomas Wymond.

Messrs. Hoskins and Bellair took over the operation of the Theatre Royal Hotel in February, Hoskins also becoming the sole lessee and manager of the theatre; and on the tenth, Mr. Brown (mentioned as a licensed victualler) assigned the entirety of his real and personal estate (39) to a trustee group made up of William Hoskins, and local businessmen George Munro and Thomas Wymond.

For a short time in April, Brown went to Sydney, possibly to sound out his prospects, and he played roles at the Prince of Wales Theatre, where the Sydney Morning Herald (41) declared him to be “an actor of decided talent, taste and discrimination.” He also acted as Stage Manager for the Royal Victoria Theatre’s production of the Flying Dutchman. By May, insolvency proceedings were underway, debtors being requested to settle their accounts promptly, and on May 10 Brown’s brick nine-room home in Errard Street was sold at auction.

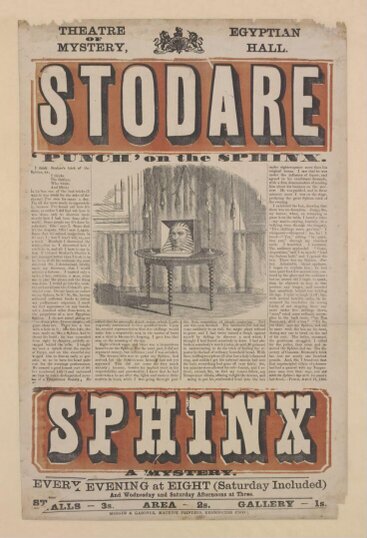

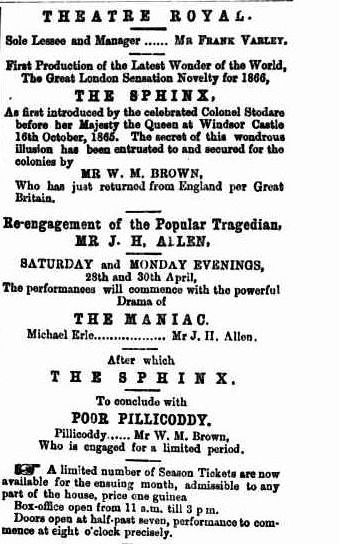

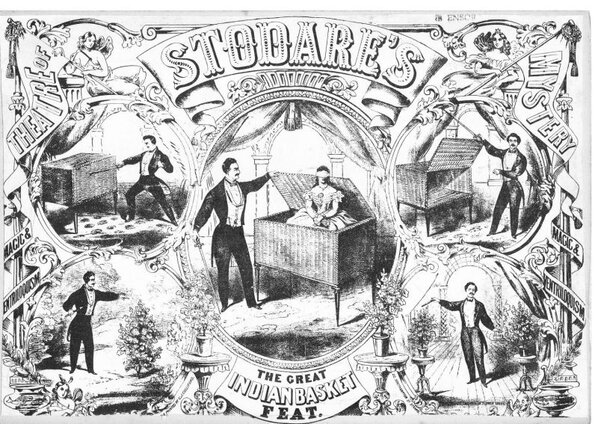

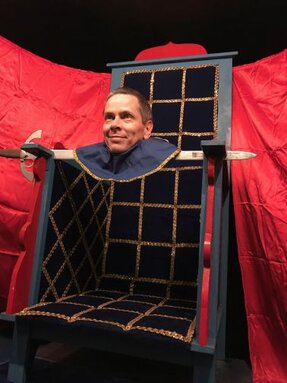

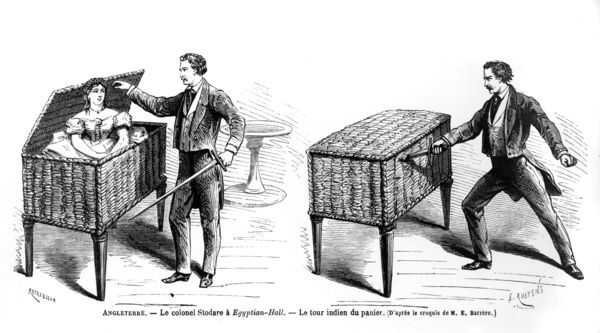

Brown the Magician - The Wizard of the N.N.E by S.S.W

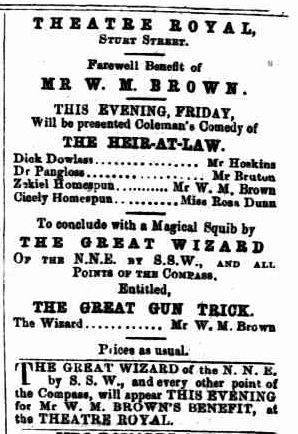

William Brown’s first dalliance with conjuring was at this time when, on May 11, he was given a Benefit night at the Theatre Royal by Hoskins and Bellair.

William Brown’s first dalliance with conjuring was at this time when, on May 11, he was given a Benefit night at the Theatre Royal by Hoskins and Bellair. He firstly appeared in a comedy titled The Heir-At-Law playing ‘Zekiel Homespun’, and then the audience was treated to a ‘Magical Squib by the Great Wizard of the N.N.E by S.S.W and all points of the compass’. The joke was on the multitude of conjurers, starting with John Henry Anderson the Wizard of the North, who had billed themselves under every direction of the compass until only NNE by SSW remained. Brown’s feat was the Great Gun Trick, which was uproariously received. This may have been either the ‘bullet catching’ feat or, more likely, the trick of loading a spectator’s watch into a funnel on the end of a gun, and shooting it magically across the stage. This was not a new item in the colonies, and perhaps “too soon” considering the death of C.H. Rignold only a year previously while performing the same feat. Brown thanked his audience for their kind attendance and hinted that he would be returning to Sydney, having had success there.

The Great Wizard made a further appearance at the Montezuma Theatre on May 21 which, for some reason, had briefly been renamed as “Punch’s Playhouse”. As a farce it was successful, but Bell’s Life of May 26 said “something of a far superior class must be presented, if the management would complete successfully with the attractions at the other house.”

At something of a loose end, Mr. Brown took on the job of Stage Director for the Charlie Napier Theatre’s production of Café De Paris and was announced as the lead player in their new drama, The Shepherd of Derwent Vale, or, the Murder at the Torrent. The manager of the Charlie, Mr Symons, was becoming disheartened at the theatre’s poor profits, and following another presentation of Will and the Way featuring Brown, he gave up the business altogether. Brown joined him in supposedly “retiring entirely from the Dramatic Profession”, having declared that this was the final production of “Will” on Ballarat. (42)

Insolvency, in the 1800s, was generally not a barrier to continued business activity, and Brown next set himself up in business as a publican, at the Sir Henry Barkly Hotel in Humffray Street, close to the intersection with Main Street. He also opened a Masonic Lodge (No. 1 Mother Lodge of Ballarat) under the ‘Brethren of the Loyal Order of Antediluvian Buffaloes’, an order which continued until at least 1950. Ironically, the new lodge’s By-laws were printed by Brown’s successors in the printing business, the Evans Brothers. Save for a taking on the job of Acting Manager and Stage Director at the Charlie Napier (which was at this time under the management of William Hoskins), Brown is not seen for the remainder of the year.

One thing can be said of William Maxwell Brown – he was not cut out to be a hotel owner. His various ventures as a publican all seem to have been failures, and probably for a common cause; he did not pay enough attention to his business. The Sir Henry Barkly Hotel was no sooner under his control than it was advertised (January 25, 1861) for lease, “Present proprietor having no time to attend to it, in consequence of other occupations .. Apply W.M.Brown”. The other occupation was his continued role in stage management at the Charlie Napier, which would shortly come to a fiery end.

Ironically, “Bell’s Life” of January 5 had complimented the management of Hoskins and Bellair, who were in management at both the Royal and the Charlie Napier which they said “appears to have taken out a new lease of life … [they] in all probability will be well repaid for their enterprise.” Nothing could have been further from the truth, for the following week Mr. Hoskins threw in the towel and retired from the Theatre Royal. He had, noted the Star, “persistently sought to provide a constant succession of legitimate novelties for the patrons of the house.”

At a benefit night on January 11, “Mr Hoskins was then called for, and was received with loud applause. He said he felt himself a perfect contradiction of the aphorism that out of the fullness of the heart the mouth speaketh, for his heart was so full he hardly knew what to say, or how to arrange the ideas crowding upon him. He then reverted to his two years' managerial connection with the theatre [Royal], and said it had now ceased, for he had no more "sinews of war" to bring to the conflict. He had loved his art and striven to uphold it in its dignity, but he had miscalculated the power of the district to support the drama thus presented. If, however, his aim to educate as well as amuse had succeeded in but one instance, he was rewarded, though he had to begin the world afresh. To the many sympathising friends before him he felt grateful.”

The Theatre Royal would pass into the hands of actor-manager Clarance Holt for a year, but Hoskins would return to the Theatre Royal in 1862 and take up the ‘conflict’ once again.

The very same night, a fire broke out on the Eastern side of Ballarat, and the origin of the blaze was thought to be in the property room of the Montezuma Theatre; probably one of the same theatrical incendiary devices that had caused a fire in the Royal a year previously. This fire, however, was calamitous – it wiped out the Montezuma Theatre, the Charlie Napier, some sixty other buildings lost and forty more damaged, with an estimated £50,000 property loss. The fire brigades, commended for their bravery but acknowledged to be lacking in cohesive discipline, were powerless to do any more than pour water on the embers to prevent a further outbreak. The owners of the Montezuma were not insured.

Not only Hoskins, then, but William Brown also, had no ‘Charlie Napier’ to keep them afloat. While plans were rapidly drawn up for the re-building of the Napier in brick (the lost building had been insured), Brown went under again – in June he declared himself insolvent for a second time, with debts of £409 caused by ‘depression in trade’, and his hotel’s furniture was sold off on June 18. Undeterred, Brown was still buoyant enough to perform in a concert at the Commercial Hotel in July. By October he was advertising as a Stationer once more, now located near the George Hotel (which still exists at 27 Lydiard Street). His name appears as the Ballarat publisher, or agent, of “Follow the Track – an Australian serialised novel written by ‘Twig’ and illustrated by ‘Stump’, which The Star complimented as being well got up, at a moderate price, and with illustrations of rare excellence for a colonial production.

1862 – 1865

Down, but not out, William Brown spent the next few years mostly away from the theatre, focusing on his stationer’s business. The Theatre Royal in Hobart, Tasmania, produced his version of The Will and the Way in June 1862, which was described as “a succession of highly-wrought scenes and ingeniously contrived tableaux, well calculated to produce effect upon the stage”. In November he sang some comic songs at a Soiree, one of which was rather too ‘free’ and lacking in propriety, resulting in a mild reprimand from a Rev. Frazer who was in attendance.

Things were improving by 1863 when, aside from the birth of a daughter in April, Mr. Brown made arrangements in March to purchase back his business, to merge his printing plant with the Evans Brothers’ “Victoria Stationery Warehouse and Printing Office” as they retired, and to move back into his old rooms next to the Craig’s Hotel in Lydiard Street. He advertised, taking ‘the opportunity of expressing his obligations to his friends and supporters who have enabled him by their assistance during the last eighteen months.’