Mr. L. Charles, Ventriloquist and Professor of Natural Philosophy

This gentleman is of particular interest because his appearances in Australia came three decades after his main career.

Having announced his arrival in Sydney in the Sydney Morning Herald of January 7, 1860, “Mr. Charles, Ventriloquist and Professor of Natural Magic" was hosted at the School of Arts in Pitt Street, on January 23 and 24, and again on March 6, 8, 13 and 14.

Normally, a ventriloquist’s talents are outside the scope of these conjuror-focused pages, but Mr. Charles declared himself to be a “Prestigiteur” and therefore worthy of investigation.

What makes Charles stand out is his repeated assurance that he was a “professor of Recreative Philosophy and Ventriloquist to his late majesty the King of Prussia” and a lengthy list of other royalty and Napoleon himself, and that he had “shown his credentials to the respective ambassadors and consuls in this colony.”

Yet, of Mr Charles, ‘Magical Nights at the Theatre’ says simply “I know nothing of him.”

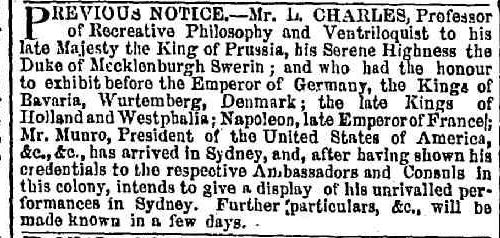

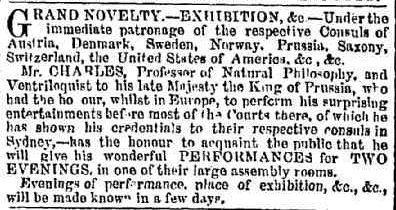

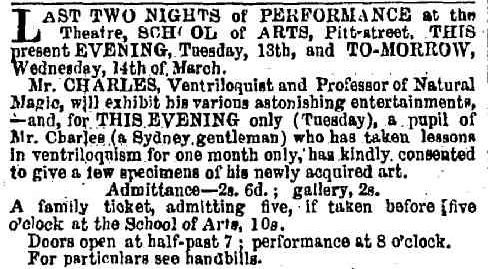

Mr. Charles advertisements of January 7 & 12, and March 13, 1860

We have one review of the March performance:-

[Empire, Sydney, March 8, 1860] – “A very pleasant evening may be spent at the School of Arts with Mr. Charles, the professor of ventriloquism and natural magic. In the most unassuming and natural manner he performs a series of sleight-of-hand tricks that are well calculated to make his audience doubt the testimony of their own senses. He is surrounded by no imposing apparatus; everything seems to be clear and above-board; to his own dexterity he seems to be indebted for all the wonderful and incomprehensible illusions he practices on our better judgment. His skill as a ventriloquist is also surprising. Clever musicians are sometimes said to make their instruments speak, but this gentleman produces eloquence from the lining of an old hat, and can call voices at least, if not “spirits, from the vasty deep.” The only thing that is wanting to make this entertainment exceedingly popular, is a little more vivacity on the part of the lecturer. Audiences assembled for amusement never like to be left to their own resources even for a minute; the many intervals of silence that occur in the course of the evening have a damping effect upon the company. Mr. Charles is by no means wanting in dry wit and humorous allusions, which he delivers in the serious and apparently unconscious manner that forms one of the chief attractions of such displays; and it would, we imagine, be comparatively easy for him to keep up a continuous stream of conversation, that would tend greatly to enliven his performances, and be likely to increase the attendance. A gentleman who has been taking lessons from the Professor in ventriloquism, will make his appearance next week, in order to show the facility with which the art may be acquired. We can safely recommend our readers to pay Mr. Charles a visit.”

Bell’s Life in Victoria February 11, 1860, carries a Sydney report stating “two entertainments, of whom report speaks highly, which, however, were not well attended.”

Little more can be said of Mr. Charles’ Sydney visits. From the history which is detailed below, it is clear that he was in Australia some thirty to forty years after his main career (1818-1829) so he must have been, by the standards of the time, an elderly man. The short-lived nature of his performances might be due to the low attendance. It seems surprising that Mr. Charles would have come to Australia solely for a short performance season; the distances required are far too great.

Is there a possibility that this was not the same Mr. Charles detailed below? The singular nature of his advertising, with its unproven bombast, archaic references to “Natural Philosophy”, the “King of Prussia”, and “Philosophical Recreations” make a connection back to his original advertising which seems indisputable.

Early History of Mr. Charles

The clues connecting the dots between this personage and a ventriloquist of the 1820s come through the advertisement of January 7, naming him as “Mr L. Charles”, and his repeated phrase regarding the King of Prussia. In some of the standard works on magical history, some patchy references to Mr. Charles can be found.

Attributed to ‘The Times’ of April 25, 1804 - a paragraph (5) referring to Mr. Charles and his French, English and German ‘Invisible Girls’ on exhibition at Saville House, Leicester-square, including a bust of the famous Pythia of Delphos. It might be guessed that the invisible and oratoric voices were, in fact, Charles’ ventriloquism.

“The Annals of Conjuring” [Sidney W. Clarke, reproduction by Magico Magazine 1983] –

“L. Charles, a celebrated French ventriloquist, performed in London and in the provinces and Ireland in 1814, and again between 1823 and 1829. combining with his ventriloquism the exhibition of mechanical contrivances and the performance of a few conjuring tricks, such as the omelette in a hat.”

“The Unmasking of Robert-Houdin” [Harry Houdini – Routledge 1909] –

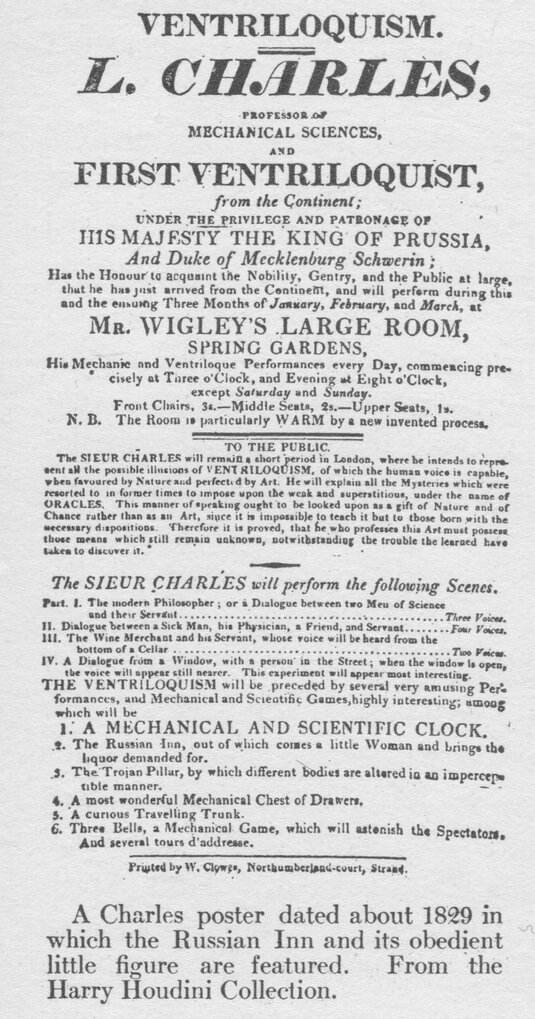

(see poster image)

“A contemporary of Henry was Charles, the great ventriloquist, who varied his performance as did all ventriloquists of his day, by presenting “Philosophical and Mechanical Experiments” to make up a two-hour-and-a-half performance. Charles made several tours of the English provinces, and played in London at intervals. On a London programme which is undated, but which announces M.Charles as playing at Mr. Wigley’s Large Room, Spring Gardens, the second automaton on his list is described as ‘The Russian Inn, out of which comes a little Woman and brings the Liquor demanded for.’ Two of his programmes dated theatre Royal, Hull, April 1829, now in my collection, carry a pathetic foot-note written in the handwriting of the collector through whom they came into my possession: ‘the audiences on both the evenings were extremely small, and the money was refunded.’ “

“Houdini’s History of Magic in Boston 1792-1915” [H.J.Moulton, Meyerbooks 1983]

Mr. Charles 1819 – This performer, who says he is a ventriloquist and professor of mechanical sciences, to His Majesty the King of Prussia, will present his grand exhibition of mechanical games and philosophical recreations on October 15 in the amphitheatre [sic.] at the Washington Gardens. Admission one dollar.Some 50 cents seats. Local notice says Mr. Charles is in town and will perform for the gratification of his partons. “Mr. Charles is a ventriloquist,” says the Centinel of October 16, “ and he gave very entertaining performances at his two exhibitions yesterday, satisfying the truth of the stories regarding his astonishing powers.” Again on October 20 notice is made that Mr. Charles will give a grand exhibition on ventriloquism and mechanical and philosophical experiments on October 21-22. The ampitheatre, it is stated, is floored, carpeted and pleasantly warmed by stoves (Coumbian Centinel, October 15-20).

Mr. Charles 1821 – Second Boston appearance on April 25 at the Ampitheatre of the Washington gardens. Will present his ventriloquism, much grave and philosophical recreation. “The wonderful chest of drawers,” “the miser’s bottle,” “Tours d’Adresse, and several instructive deceptions. Tickets, 75 – 50. On April 28 Mr. Charles says he is the only ventriloquist of France, England and the United States.

Via a useful compilation, “Nineteenth-Century American Ventriloquists” by Ryan Howard (1), these references from other works are found:-

- L. Charles, ventriloquist, Washington Hall, New York, 13-15 Sep 1819. In the Post of 2 Sep, says he “has received the applause of almost every court in Europe,” and has arrived in NY from Dublin. At Washington Hall, called himself “Professor of Mechanical Games and Philosophical Recreations to His Majesty, the King of Prussia.” Continued until yellow fever closed all amusements. Was at City Hotel, 4, 11, and 18 Nov 1819, which was his last night, according to the Columbian (Odell 2, p. 565). (2)

- Charles, Washington Hall, New York, 3 and 4 July 1820 (Odell 2, p. 572). Also 1-4 November (Odell 2, p. 1820).

- Mr. Charles: French ventriloquist and magician billed as “Professor of Mechanical Sciences to the King of Prussia.” 1821 seen by Harrington at the Washington Gardens Amphitheatre in Boston (Burns 101-103: Includes portrait and playbills) (3)

“Panorama of Magic” [Milbourne Christopher, Dover Publications 1962 – the forerunner of Christopher’s seminal work “The Illustrated History of Magic”; however the later work does not contain this detail.] -

‘The first record of Mr. Charles I have found is an advertisement for his performances of ventriloquism and magic at a room on Grafton Street, Dublin, October 22, 1818. There he featured “Physical and Mechanical Games, Oracle of Calcos, Illusions with Cards, Dice, Rings, etc.” A year later he crossed the Atlantic and appeared at the amphitheatre in Washington Gardens, Boston. He was advertised as “Professor of mechanical sciences to His Majesty the King of Prussia,” and the Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin was listed among his former patrons.

The winter chill was already being felt in Boston, so Mr. Charles stressed in his propaganda that the theatre was floored, carpeted and pleasantly warmed by stoves. In America Mr. Charles listed “the Wonderful Chest of Drawers, “The Misers’s Bottles” and sundry feats of sleight of hand in the conjuring portion of his program. In England he included “A Mechanical and Scientific Clock.” “The Russian Inn, out of which comes a little Woman and bring the liquor demanded for.” “The Trojan Pillar, by which different bodies are altered in an imperceptible manner,” “A Curious Traveling Trunk,” and “Three Bells, a Mechanical Game, which will astonish the spectators.”

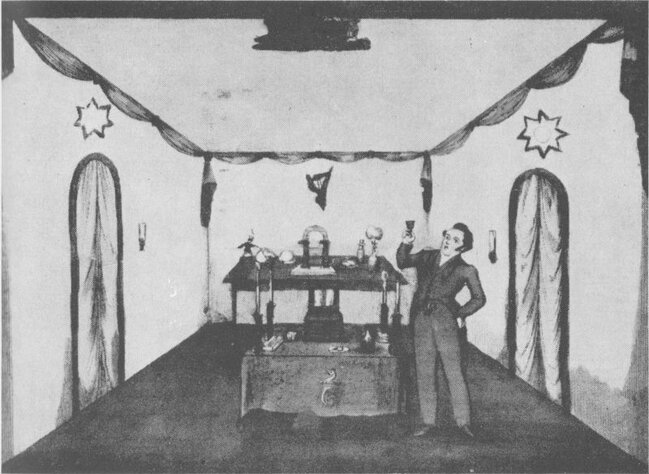

Image of Mr. Charles in Dublin, from a coloured image reproduced in greyscale, in “Panorama of Magic”

When Mr. Charles performed in Newbury-port, Massachusetts, in 1821, the local paper reported: “Mr. Charles has made his purchase of land in New Hampshire and goes to Europe for settlers. He exhibits tomorrow evening at the Theatre, prior to his departure.” What happened to the magician’s plans for a settlement in New Hampshire I do not know. In April, 1829, Mr. Charles was conjuring at the Theatre Royal in Jull, England. Houdini had programs from this engagement in his collection on which someone had written “the audiences on both the evenings were extremely small, and the money was refunded.”

Professor Edwin A. Dawes, writing in his extensive series of articles for the Magic Circle’s magazine, “The Magic Circular” (4), notes an amusing story from Dublin, reported in the British Mercury on 17 September 1823. Mr. Charles had been annoyed by the heckling from a pair of know-it-alls in the audience, and asked them onstage, where they were each invited to break an egg into their own hats, whereupon Mr. Charles’ hat produced a cooked omelette, and the others were left with egg in their hats; and on their faces. A reported court case, ending in no fine being levied against Charles, sounds very much like publicity.

From internet sources –

A dispute in Dublin between Mr. Charles and Mr.Alexandre, in which Mr. Charles hissed at Alexandre’s performance.

Ladies Literary Cabinet, [New York] November 27, 1819 – A mildly amusing anecdote of Mr. Charles playing tricks with his ventriloquial skills. Reference is made to Albany, at the Eagle Tavern.

and from the same magazine, September 25, 1818, “Mr. Charles – We understand this gentleman intends, shortly, to exhibit his great powers in ventriloquism to the citizens of Philadelphia. The alarm that has existed, concerning the prevailing fever, ever since his first arrival in our city, has prevented Mr. C from receiving that encouragement he merits. It is expected that he will return here in a few weeks, and give those of our citizens who have not seen them, and opportunity of witnessing his astonishing performances.”

John A. Hodgson's 2018 book, "Richard Potter: America's First Black Celebrity" (6) speaks of Charles' 1819-1821 travels in America, and includes some publicity anecdotes, though Hodgson himself says "very little is known about him."

REFERENCES:-

(2) Odell, George Clinton Densmore. Annals of the New York Stage. 15 vols. New York: Columbia University Press, 1927-1949.

(3) Burns, Stanley. Other Voices; Ventriloquism from B.C. to T.V. S.l.: s.n., ©2000 Sylvia Burns.

(4) “Mr. Charles and the Tale of a Hat”, The Magic Circular 77 (1983). ‘A Rich Cabinet of Magical Curiosities’ by Prof. Edwin A. Dawes

(5) Article reproduced under heading ‘From The Times of 1804’ - Wednesday April 25, in the scrapbooks of Harrie Ensor, volume 12

(6) University of Virginia Press (February 13, 2018), ISBN-10: 0813941040 ISBN-13: 978-0813941042