Professor Hennicke / Abda Shah and Madame Stella

Amongst the early performers of magic in Australia, only the lives of a few can be expanded beyond their public personas and stage names. Most are just “Professors” or “Wizards”, with scant information to give us any insight into their private lives.

Professor Hennicke, fortunately, is a little more transparent, and leaves us some avenues for further investigation. His name was Bryan Hennessy, and he spent many years as a resident of Australia, particularly in Queensland. He was a regular performer of magic shows in smaller venues such as Mechanics’ Institutes and halls, starting as an occasional semi-professional and then committing fully to the touring life.

Following the intial publication of this story, I was contacted by Paula Nevin, the great-granddaughter of Hennessy, and through her welcome assistance, many dates and details concerning the family history have now been confirmed or added. Members of the extended family now live in Sydney and along the East coast of Australia.

Sidney Wrangel Clarke’s seminal work, “The Annals of Conjuring” makes a very brief mention of Hennicke, saying, “In 1878, Professor Hennicke, an Irishman, performed with some success in Australia, and was in India in 1890.” Even a more Australia-centred researcher, Charles Waller, refers only to Hennicke’s performance at the Temperance Hall, Melbourne, in 1875 and at the Apollo Hall for a fortnight in 1878. (‘Magical Nights at the Theatre’).

Bernard Reid’s “Conjurors, Cardsharps and Conmen”, describes Hennicke as having “arrived in Australia on an immigrant ship from England, but was originally from Ireland and was possessed of a thick Irish brogue.” His real name is mentioned by the newspapers several times, most likely because Hennessy was effectively a local resident known to many. In the Brisbane Courier of April 5, 1870, one Bryan Hennessy is listed to have his name added to the electoral roll of North Brisbane. In those instances where we have an official document, the spelling “Bryan” is used, though in some more casual references, “Brian” is seen.

A question to be addressed is the pronunciation of the stage name, “Hennicke”. It might be reasonable to assume that it should be “Hennickee” to rhyme with “Hennessy”. However, between 1867 and 1870 there are numerous instances where newspaper advertisements and reviews spell the name as “Hennicker”, possibly indicating the pronunciation. In either case, he eventually reverted to Hennicke.

The final question in Hennicke’s career is whether he also adopted the stage name “Abda-Shah” at one point in his career, and this will be addressed later.

Origins and Early Days in Australia

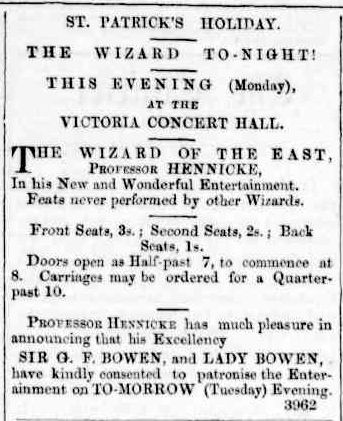

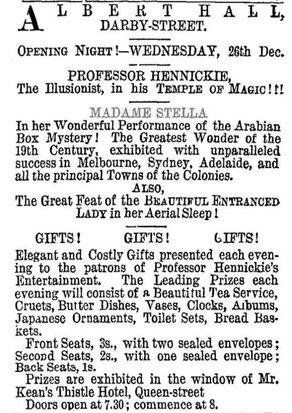

The first advertisement for Professor Hennicke is in in the Brisbane Courier of March 19, 1866 at the Victoria Concert Hall, where the good Professor gilded his name with the title “Wizard of the East” and advised his patrons that the following night’s performance would be graced by his excellency Sir George Ferguson Bowen, the first Governor of Queensland, and Lady Bowen.

The press wrote, [The Queenslander, March 17, 1866] “… judging from the very flattering notices which Mr. Hennicke has received from the press in those places at which he has performed, the lovers of the mystic art will have a treat which is not often afforded to them in this city ... Mr Hennicke, we find, has attained much of his celebrity as a conjuror in China, where was stationed with his regiment, the 2nd Battalion of Royals ... after successful performances in China, he visited France, Belgium, Germany and England.” So we have an indication that Hennicke was a military man and that he arrived fully-fledged as a performer, and the newspaper lends some credence to his travels, if they had inspected his press book.

In what was almost mandatory practice for magicians, Hennicke also declared that he had performed by command for the Empress Eugenie, the Prince of Wales, the Prince of Prussia, the Governor of Hong Kong, &c, &c. Such extravagant claims are frequently seen in magicians’ advertising, based on the assumption that few people would have the means or inclination to check the facts. However in Hennicke’s case, at least some anecdotal support for these claims is lent by the Brisbane Courier of March 21, 1866 which reveals some interesting facts of Hennicke’s earlier life:-

“This evening the masonic fraternity intend patronising Professor Hennicke ... as a benefit to their visiting brother. In reference to performances given by this wizard, we find that he appeared before H.R.H. the Prince of Wales and the Prince of Prussia at General Pennefather's quarters at Aldershot; and previous to leaving China, Mr. Hennicke gave a special entertainment before his Excellency Sir W.Robinson (1) , the Governor of Hong Kong, in the Masonic Temple; also at Jersey, brethren of the mystic tie tendered him a benefit, and appeared in full masonic costume. In Russia, shortly after the Crimean war (in which Mr. Hennicke received three wounds), he performed before the English, French, and Russian Generals.”

Bryan Hennessy (father’s name David) was born in Cappaghquinn, Waterford, Ireland in 1833. By By 1851 he was in the military, and in 1853, in Cork, he married Rebecca Phillips, whose father, Robert, was possibly military as well, as Rebecca was born in Buttevant, Cork, a military base.

By 1853 Bryan was serving in Greece where, in 1854 his daughter Ann was born in Cephalonia, Corfu. ( Ann’s marriage certificate states that her father was a musician in the military.)

In ensuing years, Hennessy saw service in the Crimea (1855), Malta (1856) and Gibraltar (1857); then from 1858 - 1860 in the Second Opium War in China. His son Henry was born in China (1860) , and two more sons, William Phillips Hennessy in 1861 (in India) and Robert in 1862 (in Salford, England)

A search of War records (https://www.forces-war-records.co.uk/) reveals that one Private Bryan Hennessy, service number 2532, was engaged in 1861 with the infantry regiment ‘2nd Battalion 1st Foot (Royal)’ and returned from Hong Kong.

In 1865 he was with the ‘1st Regiment Of Foot (No. 6 company)’ He was discharged on September 14, 1865. He had received the Second China War Medal with clasp for the battle of Taku Forts 1860. (7)

The Second China War Medal was issued by the British Government in 1861 to members of the British Army and Royal Navy who took part in the Second Opium War of 1856 to 1860 against China. The Second Anglo-Chinese War was a war pitting the British Empire and the Second French Empire against the Qing Dynasty of China, lasting from 1856 to 1860. It was fought over similar issues as the First Opium War i.e. exclusive and preferential trade ideals.

As a soldier, and through his Masonic connections in enclaves of the British Empire, Hennessy may well have performed at Aldershot for military officers. Certainly he was sufficiently well regarded in later years to be attended by the Governor of Queensland. However, on the subject of appearing before royalty, our later chapter on “The Hennicke Leaflet” will shed a more sober light.

By early 1866, the Hennessy family had moved across the world to Brisbane, Queensland, possibly for the benefit of Rebecca’s health. Sadly, it seems that Professor Hennicke’s first show in Australia was arranged with the assistance of local Masons, to help raise funds for the funeral of their son, Henry, who would have been barely five years old. Later in 1866, Rebecca Hennessy gave birth to another son, Walter; and in 1868 to son Edwin.

Bryan Hennessy was at this time supporting his family by working as a clerk.

Included in advertisements for Hennicke’s March 24, 1866 appearance at the Victoria Concert Hall, Brisbane, were some promised tricks – “suspending his daughter by a single hair of her Head, and Swinging her in the Hall, a feat unaccomplished by any other Necromancer ... Professor Anderson's celebrated Gun Trick will be initiated, in which the Wizard will Catch A Bullet in his Hand ... M. Houdin's Wonderful Egg Bag Illusion will also be given. The Davenport Brothers' Deceptions Exposed and Illustrated.” The Professor also included in his repertoire a number of feats which were, at the time, new and novel to most Australian audiences. The Needle Feat, now associated with Harry Houdini, in which needles and a length of thread were apparently swallowed, only to be regurgitated with the needles threaded, and a magic bottle which poured different drinks; Hennicke’s difference being that his bottle was entirely made of transparent glass.

The “Davenports’ Deceptions” involved Hennicke being securely tied with a rope and, after briefly retiring, escaping from the rope. It is significant to note that interest in the Davenport Brothers was no longer directed at their supposed Spiritualistic activities, but had metamorphosed into a simple challenge of wits to see whether they could escape their bonds. This, in its turn, inspired the feats of escapology for which Houdini became famous.

April 3, 1866 QLD Times

Hennicke moved on to Ipswich for a season on April 2-4, but according to the ‘Queenslander’ of April 14:- “The Wizard of the East, Professor Hennicke, had arranged to proceed per the Clarence, on Wednesday [April 11, 1866] to Rockhampton, but owing to family sickness has postponed his visit to the North for a week. Having made an unsuccessful trip to Ipswich, Mr. Hennicke has engaged the Victoria Concert Hall Brisbane for one night (this, Saturday, evening) when he purposes introducing a great number of illusions not before performed in Brisbane, together with some new experiments in Mesmerism and Electro-Biology.” Apparently the season was successful, as he remained in Rockhampton until May 2.

The Professor then drops from sight for over a year, before reappearing in Toowoomba, QLD, in October 1867, and introducing three notable changes.

Firstly, from that date until around April 1868, his advertising, in several newspapers, used the spelling “Hennicker” regularly. On the surface this seems not to have been a simple typographical error, and the suspicion is that Mr Hennessy was experimenting with his stage name in order to make it clear how the name should be pronounced. However over the ensuing years his name was sometimes spelled, even in repeated advertising, as Hennecke, Hennicker, Henecki, Hennecke, Heneckie, Henecki, Hennechi, Hennikie, Henake and Henneck so it is possible that the name variations were simple errors on the part of the newspapers, and that Mr Hennessy made no effort to correct them (his level of personal literacy might be questioned here, too). The pain which this inflicts on the humble researcher is best left unremarked.

Either way, he was almost always “Hennicke”, and he also dropped the “Wizard of the East” title except on occasion.

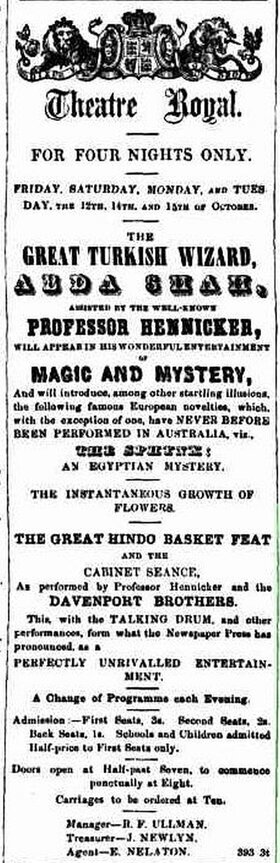

At the Toowoomba Theatre Royal for October 12-15, we find that “The Great Turkish Wizard ABDA SHAH [sometimes ABDA-SHAH] , assisted by the well-known Professor Hennicke, will appear in his wonderful entertainment of magic and mystery …”. It seems most unlikely that “Abda Shah” was other than Hennicke in another guise, although the Darling Downs Gazette referred to “the manipulation of the Turkish Wizard.” More of Abda Shah later.

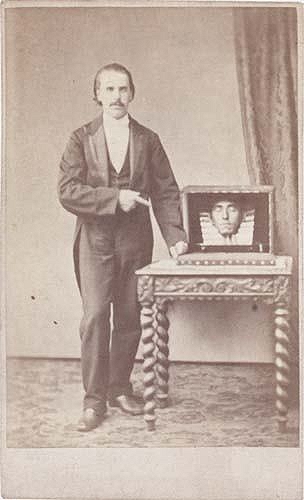

Also of note from this short season were the introduction of the “Great Hindoo Basket feat” (the Indian trick of thrusting a sword into a wicker basket without injuring the person inside), the “Instantaneous Growth of Flowers”, and “The Sphinx”. The illusion of a talking head sitting in a box upon a table, introduced to England in October 1865 by Col. Stodare, would become one of the most iconic illusions of this period and must have made a strong impact upon audiences to whom the trick was new. Hennicke, though not the first to introduce these illusions to Australia (see William Maxwell Brown) he was not far behind and would, in later years, style this as “The Sphynx”.

Stodare - Sphinx illusion

Mr Byers and Miss Julia Hudson made a concert appearance “in conjunction with the great Wizard of the East, ABDA SHAH” at a fashionable entertainment in the Brisbane School of Arts on January 13, 1868.

June 28, 1868 Brisbane Courier

Around April 21 and 24, an entertainment was given at the South Brisbane Mechanics' Institute, for which Mr. Bob Osborne provided ‘Legerdemain Comic Impersonations’ (“the hall was well filled, and the various performers gave satisfaction, Mr. Osborne's legerdemain commanding great applause.”) R.J. Osborne was an itinerant actor and comic singer who regularly featured conjuring in his performances.

Possibly he had appropriated the title Abda Shah for satirical reasons, for on April 21 the Brisbane Courier reported, “The gentleman who has given several performances in Brisbane under the names of Professor Hennicker, Abda-Shah, &c. requests us to state that he has no part in any performances at present taking place in this city, and that it is without his consent he has been publicly announced as appearing in any such entertainments.”

To which the Secretary of the Mechanics' Institute responded, in a letter to the Editor, that "Mr. Abda Shah, Professor Hennicker, or whatever else he may choose to call himself, may (colonially speaking) "shut up".

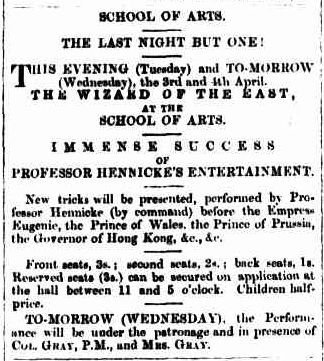

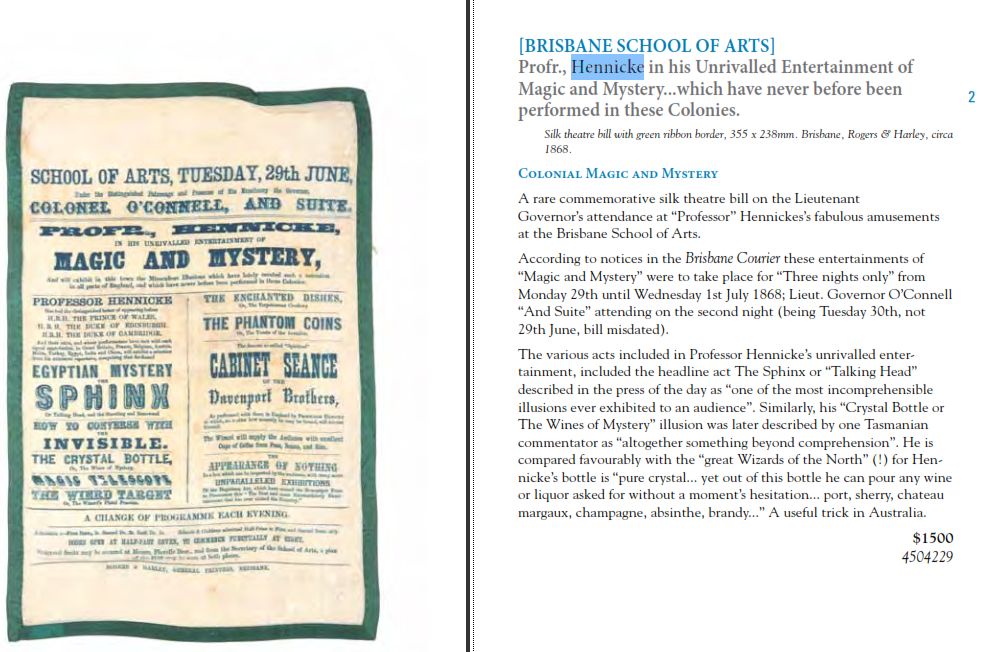

Hennicke is next seen from late June, 1868 with performances at the Brisbane School of Arts; this was one of his most regular venues, for reasons which will become clear. The quality of his magic is unquestioned; for this trio of performances he presented the Sphinx illusion, ‘How to Converse with the Invisible’, The Crystal Bottle or the Wines of Mystery, Magic Telescope, the Wizard’s Pistol Practice, Terpsichorean Crockery (plate juggling or spinning), the Phantom Coins, Coffee Vase and the Cabinet Seance (rope escape). His show of June 29 was given the honour of patronage by his Excellency the Governor Colonel O’Connell and suite. (The State Library of Queensland holds a silk handbill for the occasion) (2).

However there are some worrisome comments made by the Brisbane Courier of December 22, 1869: “we are not amenable to the charge of overstating facts when we say that he is one of the most clever "wizards" we ever saw ... many other tricks were performed, with unvarying skill and success, and it is a matter of wonderment to us that the Professor, who is a needy man, is not more cordially supported by the public. He is resident among us, possesses far more skill and talent than many foreign performers who attract crowded houses, and is in every way deserving of a larger amount of public patronage than has hitherto been accorded to him.”

Hennicke appeared again in 1869, on December 10 at the Victoria Hall, and after Christmas at the School of Arts with a programme including the Inexhaustible Hat.

A silk programme, sold in 2011 by Sydney antiquarian dealer, Hordern House

October 12, 1867

On the Road, 1870 - 1879

There follows a considerable period, almost three years, during which Professor Hennicke is rarely mentioned by the press, and then only in relation to a few brief appearances at the Brisbane School of Arts and, in May 1870, at Oxley, just outside the main city of Brisbane. In the same period, a B. Hennessy is mentioned as having been installed in the Masonic Lodges ‘Duke of Leinster’ and ‘Hiram (Irish Constitution)’ and, over the course of two years, as Secretary of St. John’s Lodge. The inference is that Hennessy was staying close to home and tending to his non-theatrical occupation.

The likely cause is the ongoing illness of his wife. On March 10, 1874 an announcement was printed in the Brisbane Courier, inviting friends of Mr. Bryan Hennessy to attend the funeral of his deceased wife, Rebecca. She was buried alongside her child, Henry, at a cemetery on which now sits the Suncorp sports stadium. Certainly, after March, Hennessy started to travel outside his usual district.

The other notable fact from this funeral announcement is that Hennessy’s residence was named as being in Adelaide Street, Brisbane; which street happens to be mere blocks away from Hennessy’s favourite performing venue at this time, the Brisbane School of Arts at 166 Ann Street. Also, by searching on that address, the Queensland Post Office directory confirms that Brian [sic] Hennessy of Adelaide-street was occupied as a Clerk.

Confirmation of his performing hiatus had been given by the Brisbane Courier on December 12, 1873, which announced that “Professor Hennicke is about to resume his old profession, commencing at the School of Arts on Monday evening next. ” Unfortunately the comeback was not a happy event.

December 13, 1873

“The entertainment given at the School of Arts last night can hardly be described as having been a success. "Professor Hennicke" has already proved himself before Brisbane audiences to be a clever conjuror; but this time he introduced nothing that was new, beyond repeating a few of the feats of the Japanese jugglers who were here some time ago. As a serio-comic songstress, "Madame Lancia" (3) was so unfortunate as to select for her first appearance "Good-bye, Charley," with which one or two professional ladies have already familiarised the public. That her attempts at mesmerism were not successful, may be attributed to the continual disturbance kept up in the gallery. Her pathetic appeals to be allowed fair play were not attended to, and the subjects upon which she attempted to operated were of the most unpromising description, being principally representatives of "the gods" who were much chaffed by their brethren in the upper region. It will be observed from an advertisement that Madame Lancia is determined yet to prove her power as a mesmerist.”

Fortunately, Madame Lancia restored her reputation in the following days, (“Considerable amusement was again caused by the involuntary contortions exhibited by the 'subjects' operated on”) and the season continued with better success until December 27. Madame Lancia, however, is not seen again in the press.

Later in 1874, Hennessy seems to have decided that it was time to go on the road, but not as Professor Hennicke. The Sydney Morning Herald, from August 11, 1874, started promoting the upcoming appearance of “Abda Shah the Marvellous Necromancer and Mysteriach” at the School of Arts (4), Sydney, from August 17. There is little doubt that this was Hennessy, who repeated his string of foreign accomplishments, and performed the “Sphinx” or “Sphynx” illusion. New Zealand magical correspondent, Robert Kudarz, wrote "at one time in Australia he made up as a Turk and performed a silent act in a variety show. He assumed the character during the day, but 'gave the game away' at the dinner table in a Queensland County hotel on one occasion, when he requested one of the diners to 'oblige by passing the spuds along' with an Irish brogue that could be cut." [M-U-M magazine for magicians, May 1920]

School of Arts, Sydney

The timing of Abda Shah’s season, heading up the “New Star Alliance Troupe”, was interesting on a number of points. Arriving the same week to perform at the Domain, was the famous rope-walker of Niagara Falls fame, “Chevalier” Charles Blondin. (6)

A newspaper report of August 18 (Sydney Morning Herald) stated that a delivery van standing outside the School of Arts was startled by a passing wheel-barrow, and bolted down Pitt Street before colliding with a cab and capsizing. Damage to goods in the van was said to be the equipment of Blondin, but the next day a correction was made; the goods belonged to Abda Shah, who as a result of his best tricks being broken, had a makeshift opening night, but recovered by the following evening. Also in his troupe was Signor Ferrari’s trained monkey act, Luscombe Searell the youthful piano prodigy, Mr. Margetts the comic, and female impersonator, Mr. Bromley.

Blondin

At both the Queen’s Theatre, York Street, and the School of Arts immediately preceding Hennessy’s season, Madamoiselle Zelinda was concluding her run, in which her sole featured routine was the “Arabian Box Mystery”. This was a forerunner of the modern “Metamorphosis” or Transposition trunk, in which a travel trunk was bound in rope, and a canvas cover buckled over the whole; yet after three minutes with the trunk concealed by a canopy, Mdlle. Zelinda was found inside the trunk, tied up in a sack. Zelinda was, according to the Ilustrated Sydney News, “a young lady whose knowledge of Turkey has hitherto been confined to the dressing of that indigestible bird for dinner.”

Following hot on the heels of Mdlle. Zelinda, Abda Shah moved into the School of Arts on August 18. Zelinda moved on to Bendigo and Melbourne, then to New Zealand, meeting with an unfortunate business conflict between her management team. (5) With barely a how-de-do, and never having advertised the trick before, Abda Shah commenced promoting the inclusion of the Arabian Box Mystery in his own act alongside the Sphynx, though the trick was presented by “Madame Mira”.

It is interesting to note the number of occasions on which Hennicke made an astute change to his programme. As with “Abda Shah” and “Madame Mira”, he would advertise a show featuring his standard repertoire of magic, but frequently with another performer billed as a magician and often above his own name. This would have had the effect of making his audiences feel that they were seeing a whole new show when, in fact, the lead performer was probably hired and trained by Hennicke to present magic with props that he owned.

Abda Shah, patronised by Chevalier Blondin on August 22, continued at the School of Arts until September 11, 1874, then moving north to the Theatre Royal, Newcastle, on September 19 with the New Star Company. Although the ‘Evening News’ had stated that “the patronage bestowed upon the entertainment at the School of Arts is not adequate to the merits of the performance; and this is a matter of regret, especially as it is very rarely we can get such a versatile drawing room entertainment as that given by Abda Shah”, they were contradicted in coming days by the S.M.Herald which said the troupe’s Sydney shows “continue to draw good houses”, “has been very successful” and “the hall was literally crammed.”

There is some speculation that Hennessy might have made a brief journey to New Zealand sometime during 1874, working alongside Neville Thornton and “La Petite Amy” (5), who was appearing in a version of Robert-Houdin’s Ethereal Suspension. At this stage, definitive documentation is still to be found.

Jean Eugene Robert-Houdin and his Ethereal Suspension

Back in Newcastle, Abda Shah had, by October 3, turned himself back into Professor Hennicke, and joined forces with a well-established dog and monkey act, Mr. Barlow, and instrumentalist Mr. Goulstone, and would travel with the “Barlow Troupe” for some time to come.

The New Star Company went their own way, moving southwards to Goulburn. Madame Mira continued to perform the “Arabian Box Mystery” and the “Sphinx”. Mdlle Zelinda might have been the earliest and most successful presenter of the box mystery, but within a short time it seemed everyone was jumping aboard the bandwagon, starting with a cheeky male performer in Ipswich who blatantly called himself “Zelrinda”! The names of Madame Mira, Madame Zara, Thiodin and Professor Quick are amongst those who capitalised on the Arabian Box Mystery; further research is expected to reveal that most of these were short-lived opportunists who would be seen on the magical stage for only a short time. Madamoiselle Zelinda eventually milked the illusion for all it was worth and, on January 30, 1875 (Apollo Hall, Melbourne), announced that she would perform the trick in full view for the audience to see. She had returned to Australia after a disastrous season in which her managers had a falling out.

By the end of October 1874 the Barlow Troupe had made a jump to Launceston, Tasmania, at the Mechanics’ Institute. "Professor Hennicke", said the Cornwall Chronicle, "excels in his illusions any of those who have yet visited Launceston, and his quiet unostentatious style carries everything before it ... his card tricks are novel and perfectly executed, and other illusions depending evidently upon mechanism for their effect are perfect... the great Wizards of the North, the Wizards Jacobs, Ion, Haselmeyer and others astonished their audiences with inexhaustible bottles, but they were regular black bottles and might have had any amount of machinery concealed within. Hennicke's bottle is pure crystal ... yet out of this bottle he can pour any wine or liquor asked for without a moment's hesitation." The Needle Supper and Haselmeyer’s Magic Drum were also singled out for particular praise.

The company moved further south to the Theatre Royal, Hobart, where they played with success until early December 1874, then moving across to Adelaide, South Australia, adding the Brothers Franks (minstrels and dancers) to the troupe and playing until Christmas Eve despite the ferocious summer heat. This was certainly a high point in Hennicke’s career, the Theatres Royal of both Hobart and Adelaide being a substantial step up from his usual mechanics’ halls. Hennicke once again exhumed his old title “Wizard of the East” in advertising.

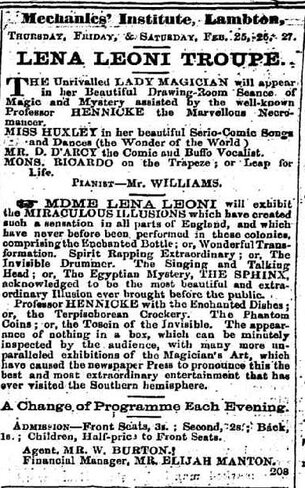

Hennicke struck out on his own again, visiting the Mechanics’ Institute at Lambton near Newcastle, NSW in February 1875, and Harris’ Assembly rooms in March. Once again the advertising heavily emphasised a female magician, “The Lena Leoni Troupe” assisted by Professor Hennicke and including some comics, vocalists and a trapeze artist. Madame Leoni, though promoted as “the unrivalled lady magician”, performed Hennicke’s Invisible Drummer, Enchanted Bottle, and Sphinx routines, with Hennicke taking a more modest role with plate spinning and coin tricks.

February 24, 1875, Miners Advocate NSW

The group moved down to Sydney, at St.George’s Hall, but by May 1875 Madame Leoni’s name had vanished from advertising, and it was stated that “Professor Hennicke has been specially engaged to assist Mdlle [Blanche] Neville”. Quite the contrary; Mdlle Neville had been engaged to assist Professor Hennicke!

Lena Leoni was seen in the press during the remainder of 1875; it seems that she may have been a young or even child performer, as she was billed as a Séance assistant in August with “Lu Zeera the Circassian Lady Magician, Wizardess and Fire Queen, and her Entranced Girl, Lena Leoni”. Blanche Neville, on the other hand, was never heard from either before or after her association with Hennicke, which ended in June.

Relatively little is seen of Professor Hennicke for the remainder of 1875, aside from a few performances in the closely-spaced towns of Gundagai, Adelong, and Wagga, NSW in August and September, then in Beechworth, Victoria on November 25 – possibly he made other small appearances in regional townships.

Madame Stella

It is in Gundagai that we first encounter the name, “Madame Stella” and strike some problems. In later years, Hennicke is known to have been married to the ‘Madame Stella’ who toured and performed with him; the difficulty is in tracing this relationship back to its beginnings and correctly identifying the lady in question. At present there is no definitive answer, even in family circles, and the available clues are documented here, pending further clarification. It is known that Bryan Hennessy’s first wife died in early 1874.

At Gundagai, August 19 1875, Hennicke was struggling to make a strong performance in an unsuitable room, and with his pianist, Mr Goulstone absent through illness. “Professor Hennecke [sic.] did his best to relieve the monotony of the evening by performing some capital card tricks, in which he displayed peculiar skill in the art of legerdemain … Miss Stella Anderson (daughter of the famous wizard of that name) exhibited her skill in magic and performed some sleight-of-hand tricks. The entertainment is varied and diverting.” [Gundagai Times]. The alleged relationship to John Henry Anderson can be discounted as publicity puff.

Again, on November 25, 1875, the Ovens and Murray Advertiser announced an appearance in St. George’s Hall, Beechworth by the ‘Cosmopolitan Troupe’. “The entertainment is a varied one, and the company consist of Professor Hennicke, a conjuror of real merit; Mr King, a comedian; Miss Stella Anderson, magicienne; Miss Kate Barry and Mr W.Gregg.”

Was this Stella Anderson any connection to the future bride? There is no certainty, since in the near future Hennicke would perform in conjunction with another “Stella” in New Zealand.

By late February in 1876 Hennicke had drifted as far south as Wangaratta, Victoria, for two nights. In a first reference to Hennicke’s performance of his version of Robert-Houdin’s Ethereal Suspension, the Ovens and Murray Advertiser said, “We note that Professor Hennecke, in conjunction with Madame Stella, will appear at St. Patrick’s Hall, Wangaratta, on next Saturday and Monday evenings. Mr Hennecke will perform his magic tricks, and Madame Stella will perform the celebrated suspension feat, after the mode of the Fakir of Oolu”. [Alfred Silvester, a British magician, had improved the suspension feat performed in Australia in 1874; but the illusion, first introduced by Robert-Houdin in 1847, had been seen in Australia as far back as 1856 in the acts of Wizards Jacobs and Eagle ].

Finally on March 18, Hennicke made his first appearance in Melbourne, Victoria, as part of the “People’s Concerts” at the Temperance Hall in Russell Street and other locations in nearby Prahran and Fitzroy through to June 13. His feature illusion was the suspension, under the title “The Enchanted / Entranced Lady”, but if Stella Anderson was still with him, she is not mentioned.

Hennicke in New Zealand, 1876 - 1878

After a brief pause, Professor Hennicke resurfaced, this time not in Australia, but in New Zealand. If he had made any previous visit, the documentation is unclear, though it must be said that New Zealand newspapers were so lax in their spelling of his name that locating him becomes a challenge. In 1876, Hennicke is frequently referred to as “Hennecke” among many more ludicrous variations of his name.

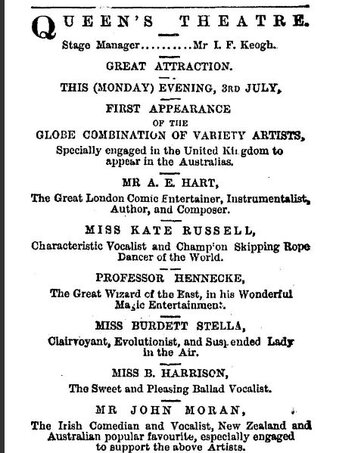

On June 26 a company named as the ‘Globe Variety Troupe’ and the ‘Globe Combination Troupe’ [but more accurately, 'Hegarty’s Globe Combination Troupe of Variety Artists’], opened at the Theatre Royal, Invercargill, on the far Southern tip of New Zealand.

July 4 sees a report from the Otago Daily Times that “Hennecke” had appeared the previous night in the Queen’s Theatre, Dunedin with and “met with a most enthusiastic and well-merited reception”.

In the advertising for this show, “Miss Burdett Stella” is listed as ‘clairvoyant, evolutionist, and Suspended Lady in the Air.’ Deciphering Stella’s real name remains a challenge until further documentary evidence can be located. Which was her first or surname – Burdett or Stella? Since other advertisement spells the name “Burdette” or more frequently, “Burdetta”, which is correct? Is there any connection to the previously-mentioned Stella Anderson? Does the fact that she is referred to as “Miss” and later as “Madame” Stella imply that a marriage took place in this period?

The Queen’s Theatre season continued to July 10, and the reports mentioned Hennicke’s magic as “clever tricks, some of which were, however, rather ancient …. after the stale “Suspended Lady business” Mr Hart and Miss Russell sang….”

July 3, 1876, Dunedin

On August 5, the troupe opened in Christchurch on the East coast of New Zealand’s South Island, for an announced twelve-night season at the Oddfellows’ Hall. The troupe included, besides “Professor Henecki [sic.] and Miss Burdette Stella”, a comic entertainer and instrumentalist, a champion skipping rope dancer, and two vocalists. The season appears to have been successful, and the troupe moved to nearby Lyttelton on August 22 and 23, with a Wellington opening at the Theatre Royal advertised for August 26.

The New Zealand press now decides to start referring to “Professor Hennicki and Miss Burdetta Stella”, but the Theatre Royal season continued until September 5, then the troupe sailed on board the s.s. Rangatira for Napier. Shipping News reveals that they returned to Wellington on the same ship on October 5 and seem then to have proceeded northwards to Featherston.

(No other advertising has been found during September. It may be that the townships played were not large enough to warrant more than local promotion.)

Following the trail of advertisements placed for the Hegarty Globe Combination, these were the tour dates until the end of 1876. Advertising frequently mentioned only the name of the company, but occasional press reviews confirm that Hennicke and Stella remained with the troupe.

October 1876

Featherston, Odd Fellows' Hall, advertised for around 5 but may have been deferred.

Greytown, Forester's Hall, 6 and 7

Masterton 10-12

Carterton 13

Featherston 16

Upper Hutt 17

Lower Hutt 18

Wanganui 20 ‘for five nights’

November 1876

Wellington, Theatre Royal, November 1 "for three nights only previous to their departure for Australia." In combination with the Bates-Howard Company. The company may have intended to head for Australia but they certainly did not.

Lyttelton, Oddfellows' Hall, 6 and 7

Akaroa 8 and 9

Oamaru, Masonic Hall, 15

Timaru, Mechanics' Institute, 28

December 1876

Milton, St George's Hall, 7

Tuapeka, Storry's Commercial Assembly Rooms, 9

Cromwell, Athenaeum Hall, 13 'for three nights'

Arrowtown, in week prior to 20

Queenstown, Town Hall, 19-21

Invercargill, Theatre Royal, 26 to January 3, 1877

January 1877

Riverton, Oddfellows' Hall, 4

Dunedin, Princess's Theatre, 11

Bruce, St George’s Hall, 17 and 18

Wellington, Oddfellows' Hall, 20 for four nights

February 1877

Greytown, (5?)

March 1877

Palmerston, Foresters' Hall, 5 and 6. Noted as including sleight of hand, suspension, Arabian Box Mystery.

Bulls, Town Hall, 9

Marton, Town Hall, 10 and 12

Wanganui, Oddfellows' Hall 13 'for rest of week'

Marton return, Town Hall, 21

Carlyle, 24 and 26?

April 1877

Thames, Theatre Royal, 14, 16, 17 and 21 including Lieutenant Herman the Great Ventriloquist.

Tauranga, Temperance Hall, 28

May 1877

Coromandel, 29

Advertising of Hegarty’s troupe, and associated mentions of Hennicke start to fade out around June, until the Hegarty company is re-announced with a new group of twelve performers. The likely cause is that the programme of the former troupe had exhausted all the available venues in the country.

In July 1877, Professor Hennicke struck out on his own and, while not appearing quite as frequently as before, he still managed to move around considerably. The Waikato Times of August 2 makes an interesting remark, “… the aerial suspension by the elbow, on a slight wooden pole, not two inches diameter, for fully quarter of an hour, was well sustained by Madame Stella, under the presumed influence of mesmerism.” Madame Stella must have been a strong performer! Around this time, Md. Stella is specifically mentioned in a review as the wife of Professor Hennicke.

July 1877

Auckland, Albert Hall, 18, 19, 21

August 1877

Cambridge, 6 and 7

Alexandria, 8

Te Awamutu (9?)

Hamilton, Le Quesne's Hall, 4 and a return on 10, 11, 15, 16 with gift-show giveaways.

Ngaruawahia, 17

Onehunga, 18 with some dispute about whether the ropes on the Arabian Box had been cut.

September 1877

Thames (Grahamstown), Theatre Royal, 8, 10, 11

Wairoa (29?)

Aratapu (30?)

October 1877

Dargaville, Public Hall, noted as three nights, undated; takings exceeded 70 pounds.

Te Kopuru, Te Kopuru Hall, two nights (3 and 4?)

November 1877

16 "Professor returns to Auckland after playing to crowded houses in Russell and Kawakawa"

December 1877

Auckland, 1

Auckland, Albert Hall, 26 to January 1, 1878

December 26, 1877, Auckland Gift Show

January 1878

Immediately coinciding with the announcement of Hennicke’s final night in Auckland, American magician and ventriloquist, Ben Allah (pseud. of Fred Whitney), took over at the same hall, featuring a “gift show” in the same style as Hennicke’s. The gift show format, where supposedly valuable gifts were given away to audience members, could be done on the basis of random selection of audience members who had already bought a ticket. In Ben Allah’s case (and he was soon charged with violation of lottery laws) it appears he favoured selling extra ‘chances’ during the show, creating a hot-house atmosphere which excited the audience to buy more. This would be the equivalent of what, in modern times, is known as a “jam auction.”

Professor Hennicke aligned himself with Ben Allah, and the joint show proceeded to Onehunga Masonic Hall on January 10 (... 'the building had never been so packed.'), to the Thames Academy of Music on 17 and 18, then to Napier on January 19. Hennicke was promoted as the magician, Allah as primarily a ventriloquist.

On January 25, the s.s. Hawea left towards Hawke's Bay and Wellington, carrying Ben Allah and his wife, but Hennicke and Stella were not listed among the passengers. Instead, on February 27, the s.s. Malcolm departed Taranaki, destined for New Plymouth and southern ports, carrying the duo away after a short-lived combination with Ben Allah. In later years the two magicians would again join forces in the far East.

March 1878

Nelson, Masonic Hall, 2, 6, 7. Hennicke’s show continued to feature the Box Mystery and the Suspension.

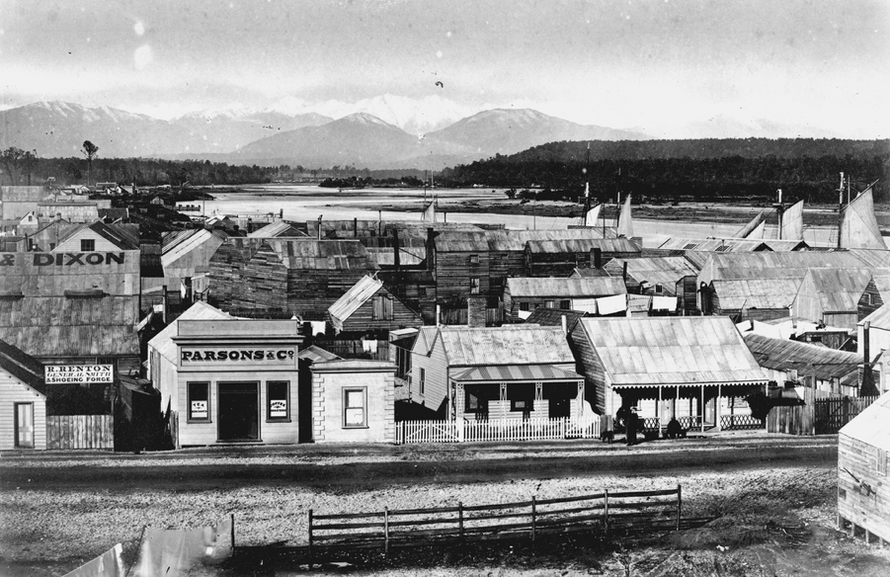

On 11th, they shipped out for the West coast, arriving in Westport March 15. As the hall there was already in use, they moved on to Hokitika in the gold-rush region.

In Hokitika, at the Duke of Edinburgh Theatre, the season was extremely successful and played March 18 right through to 30.

Hokitika, New Zealand, circa 1870

April 1878

Kumara, Theatre Royal, 6, 8, 9, 10

Greymouth, Public Hall, 13, 15, 16, 18, 24, 25

Reefton, Dawson's Hall, 27, 29, 30

May 1878

It is likely that appearances were made in other small towns during May, but no advertising is seen.

Greymouth, Public Hall, 24 and 25

June 1878

Westport, Masonic Hall 1, 3, 4

Headed for Charleston but cancelled

July 1878

It was reported on July 2 that the duo was still in Westport, "weather-bound by the frightfully tempestuous season."

Headed for Nelson on July 9

Nelson, Masonic Hall, 10, 11

Sailed for Blenheim, July 15

Blenheim, Ewart's Hall, 20 and 22

Havelock and Picton ?

Renwick, Town Hall, 29

Shipped to Wellington August 8

Return to Australia and Journey to the East

On August 11, 1878, Hennicke and Stella departed Wellington for Melbourne, Australia, on the s.s. Albion, arriving on August 23.

Back in Australia, and after a month’s break, Hennicke and Stella commenced appearances at Melbourne’s new Apollo Hall from October 5. The hall was built in 1872, in Bourke Street, after the former Haymarket Theatre had burned down; it seated 1000 people. The building survived as the ‘Eastern Arcade’ until demolished in 2008.

Eastern Arcade building 1877

As before, the main attractions in the act were the Arabian Box Mystery, the “Entranced Lady” or “Aerial Sleep” suspension, along with the smaller items in Hennicke’s repertoire, the Flying Cage and the Needle Supper. Always alert to a contemporary opportunity, Hennicke introduced “Dr. Slade’s Slate Trick”, in which ‘spirit writing’ appeared on two school chalkboards. The notorious spiritualist, Doctor Henry Slade, was in Australia and conducting his séances. The newspapers remarked that “People who have seen both Dr. Slade and Professor Hennicke, the conjuror alluded to, state that the latter does the slate trick in quite as mysterious a manner as the former; and the conjuror has quite taken the wind out of Dr. Slade’s sails. So many conjurers are now performing the slate trick that it is about time that Dr. Slade should cease to make so much of it as he does.” [Chronicle, November 1, 1878]

On Saturday, October 26, 1878, Hennicke made a final appearance in Melbourne, at the People’s Concerts in the Fitzroy Town Hall. Two more performances at the Masonic Hall, Portland, saw the last of Hennicke in Victoria, and in December the theatrical news reported that he and his wife had shipped out for Bombay, India aboard the s.s. Siam.

Final Years, Final Mystery

The obvious difficulties of tracking Hennicke through countries with fewer English-language newspapers means that his trail fades somewhat in the next decade, but there is enough evidence to indicate that Professor Hennicke continued to be an active professional conjurer.

[Australasian, Melbourne, news from Bombay on January 26, 1880] – Another troupe has only just left us for the interior – Washington Norton and Professor Hennicke, Ben Allah, and Madame Stella the entranced Lady.

Gibeciѐre journal (9) mentions Hennicke visiting Japan in 1880.

[The Lorgnette, Melbourne, April 9 1880] – Washington Norton, eccentric comedian and minstrel, accompanied by Professor Hennicke, Ben Allah and Madame Stella (entranced lady) are on tour Burmah-wise. They did tolerably well in the Indian Presidencies.

[London and China Telegraph, April 7, 1880] – Professor Hennicke and Madame Stella continue to astonish the natives by their clever tricks. [Though it might be assumed that their audiences were primarily European ].

[London and China Telegraph, June 1, 1880] – Professor Hennicke and Madame Stella have been giving their performances in the pavilion on the green and were favoured with good [audiences].

In 1881 Hennessy was married to Emma Maria Morgan, in Bangalore, Madras, India. There seems no reason to doubt that Emma was ‘Madame Stella’, but the connection to the use of the name ‘Burdetta Stella’ remains unclear.

[Melbourne Punch, September 22, 1887] – Professor Hennicke touring India.

In the promotional leaflet which will be detailed below (“The Hennicke Leaflet”), a great many dates and places are quoted by Hennicke and, with appropriate caution about his claims to have performed for many Maharajahs at their palaces, these dates fit within the known timespan of his absence from Australia:-

Grand Road Theatre, Bombay, January and February 1879

Deccan 9, 13, 24 March 1879

Simla 4, 11 18 July 1879

For Maharajah of Benares, at Palace, 15, 16, 17 December 1879

In Pavilion at Maidan, Calcutta, Janary and February 1880

For Maharajah of Mysore, 24 & 25 March 1881

For Maharajah of Vizianagram, 15 & 16 November 1882

Rawalpindi, 23 & 24 November 1886

For Maharajah of Cashmere, 19 & 21 December 1886

For Maharajah of Patiala, at Patiala, December 1887

For Highness Raja Saheb, Maharajah of Jhind, 27 & 28 February, 1887 and 1 March, 1888

Also mentioned in the leaflet are dates between 1879 and 1885 with no location listed, but the name of commanding military officers detailed.

Meeting with Rudyard Kipling

A fascinating encounter took place in 1885 between Hennicke and his wife, with famed author Rudyard Kipling. Writing in his diary, at Lahore (then part of India), Kipling noted:

Monday 28 September: .... Easy day. Went to Hennicke's performance with [illegible] and held converse will [sic] professor and wife. Motherly old woman who ought not to be in tights and spangles. Gave me idea for 'Mummers wife.’

Aside from the unflattering remark about Mrs. Hennicke, the concept that she gave him an idea for his writing is interesting. The book, “The Mummer’s Wife’, was not by Kipling, but had been published in 1885 and was written by George Moore. It was a landmark novel, the first ‘naturalist’ or ‘realist’ in English literature, moving away from traditional romantic fiction. It concerned a woman who deserts her asthmatic husband to travel with a handsome actor. In contrast to stories of the time, she finds herself in a progressive decline, finally dying an alcoholic in a London slum.

Kipling’s “idea”, therefore, seems to have been to write his own tales in this style, and in the 1890s he, along with other writers such as Somerset Maugham, would pen tales which fall into the category of ‘slum fiction’. Whether the inspiration of Mrs. Hennicke can be linked to a character in his writing, is yet to be determined.

While the Hennessys were still away, there were two notable family occurrences in Australia. Their daughter Ann died in Sydney in 1888, and in the same year, son Walter married; his marriage certificate states that his father was a bandmaster, an echo back to Bryan’s military days.

May 3, 1889 saw Professor and Mrs. Hennicke returning by ship from Calcutta to Melbourne. A further brief insight into the private life of the Hennessy family is revealed by an advertisement in the Sydney Morning Herald, June 22, 1889 saying “If this should meet the eye of Mrs. Ann Hilliard, Robert, Walter, or Edwin Hennessy – please write to your father, Professor Hennicke, General Post Office, Melbourne.” These were all children of Bryan, but Walter was estranged from their father, Robert seems never to have seen the notice, Edwin’s whereabouts was unknown, and it appears that Bryan was not aware that his daughter, Ann, had died the previous year.

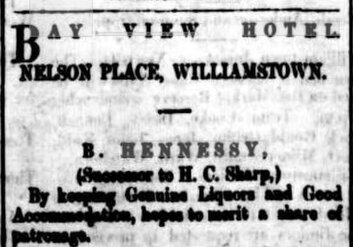

Finally, the “Lorgnette” reported [December 28, 1889] that, “Prof. Hennicke, the Royal illusionist, and his wife, Madame Stella, who recently returned from India, have settled down in Williamstown, where the professor has taken the Bay View Hotel, under his right name (B. Hennessy), instead of his nom de plume by which he was known in the professional world. In order to make hotel attractive he gives free exhibitions of his wonderful powers in legerdemain.”

January 25, 1890

Hennessy had apparently taken on the Bay View Hotel licence earlier in the year, meeting with a small fine in November for leaving the bar’s entrance door open on a Sunday. It was a short-lived enterprise, as on March 5, 1890 Judge Molesworth authorised the transfer of the Bay View’s license from Bryan Hennessy to Edward J. Keane.

It is pleasing to note that, on April 3, 1890, Professor Hennicke came back to life for one night only, at the Mechanics’ Institute, Williamstown (close to Melbourne). For a magician who spent several decades entertaining audiences in smaller venues throughout Australia, New Zealand and countries of the East, he seems to have been successful, always well reviewed by the press, and vigorous in his passion for performing.

But what of his final days?

Old magicians never die, they simply disappear. In the magicians’ magazine, “The Sphinx”, of January 1905, ‘our New Zealand correspondent’ notes “Professor Hennicke is still in the magic circle, and when last heard from, was in Lucknow, India. He was the first conjuror to do the Arabian box trick in New Zealand, and he is still working the "needle supper," and "dancing plates," with which he surprised colonials in the '70's.”

Through family research we know that Bryan Hennessy died in India. Transcription from the Wellington Cantonment Cemetery reads “Sacred to the memory of Bryan Hennssay [sic], known as Professor Hennicke, who departed this life on the 4 April 1905, aged 79 years.”

The Hennicke Leaflet

One of the more intriguing items of Hennicke’s history comes from an original publicity leaflet in the author’s collection (images below). A four-page flyer, printed on three of the pages, it was printed by the Daily Post in Bangalore. Since the final date mentioned in the leaflet is 1888, and Hennicke returned to Australia in 1889, it is reasonable to date the leaflet at late 1888.

As detailed above, the leaflet lists many dates and places in India where Hennicke and Madame Stella performed, and it is quite likely to be an accurate listing. On the subject of the many dignitaries and Maharajahs he claims to have performed for, a little more circumspection is called for, though his claims are not incredible.

The degree of caution needed is shown by Hennicke’s major claim - that he performed for Her Majesty Queen Victoria at the Queen’s Pavilion, Aldershot (the military garrison and training camp in Britain), hence his title “The Royal Illusionist”.

On the back page of the leaflet, Hennicke quotes the newspaper, “Sheldrake's Aldershot and Sandhurst Military Gazette 11 July 1863” with a glowing testimonial to his appearance before royalty, and some twenty-five years later, nobody would have the interest or resources to fact-check his quote. However, there are inconsistencies which do not add up. In his advertising through Australia in the 1860s, Hennicke had always said that he appeared before the Prince of Wales at Aldershot, not the Queen. The quotation names him as “Lieutenant”, which does not match his official records. He is named as “Hennicke”, when in fact that was his stage name only. And, most, obviously, the description of an astonishing trick where three human heads floated in the air and sang the “Jubilate” is so far-fetched as to raise immediate suspicion, although a static "sideshow" illusion of this nature did exist. (10)

Fortunately, the Aldershot Gazette is available online for viewing, and the reality is rather more prosaic than Hennicke’s promotion. He had performed on that date, but only for an audience of non-commissioned officers. There is no mention of any royalty, or a grand pavilion, and although the review of Hennessy/Hennicke’s performance is full of praise, there are no floating heads, and no invitation from the Queen to visit Windsor Castle. A close search of this newspaper’s other issues reveals no sign of other magic performances or royal attendance at Aldershot.

The two quotations are shown here. It is hardly surprising to find that a magician has exaggerated his resume, but it seems safe to say that for publicity purposes, Hennicke’s view of his talents had grown very much rosier as the years went by!

From the leaflet, pages 1 and 4:

Prof. Hennicke

The Royal Illusionist

From St. James' Hall, London, who has had the honor of performing at Aldershot under the DISTINGUISHED PATRONAGE AND PRESENCE OF Her Most Gracious Majesty Queen Victoria at the Queen's Pavilion, Aldershot.

Attributed to Sheldrake's Aldershot and Sandhurst Military Gazette 11 July 1863

“After the Review on Thursday last Her Majesty the Qeen, His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales, His Royal Highness Prince George of Cambridge, the Commander-in-Chief, and several foreign officers of distinction visited the South Camp Pavilion by Invitation of General Penufather [sic.], Commanding the Aldershot Division, to witness the remarkably clever performance of Lieutenant Hennicke, 2nd Battalion, 1st Royals. Several ladies and nearly the whole of the officers stationed at the camp were present. The Pavilion was most tastefully decorated for the occasion. Mr. H. went through the varied and extraordinary feats as a finished artist, and acquitted himself to the entire satisfaction of his Royal patrons. The Cherubs or floating heads was a great attraction. This Marvellous Illusion is beyond description. Three human heads completely unconnected with the body, with golden hair, white wings and beautiful features are seen floating gracefully in mid-air, singing in trio the Jubilate in a clear and artistic manner. The effect of this beautiful Illusion is heightened by the stage being illuminated with the lime-light. Mr. H. performed in evening costume, at the fall of the curtain appeared on the stage in his uniform with three medals and clasps on his breast, and was loudly applauded. Her Majesty was highly pleased, invited Lieutenant Hennicke to repeat his performance before the Royal Family at Windsor Castle on Tuesday next, the 21st instant.”

Actual review from Sheldrake's Aldershot and Sandhurst Military Gazette 11 July 1863

"On Monday evening a magical entertainment was given in D Schoolroom, South Camp, by B. Hennessy, bandsman in the 2nd Battalion 1st Royals, before a crowded audience principally consisting of the non-commissioned officers and men, and their wives, of the above regiment.

B. Hennessy (or as we might well term him, Professor) who bore on his breast three medals and clasps, on coming forward was well received, and proceeded to deliver a few introductory remarks.

The performer then proceeded to astonish his audience with some really clever magical tricks, in quick succession bidding cards chosen by the company rise from the pack, with a touch of the "magic wand"; putting together a card torn in pieces; exhibiting the wonderful powers of the Crystal Bottle, which produces every description of known wine, as well as milk and ink; the "miraculous pumping of a man" (an operation that threw the audience into roars of laughter), the wonderful egg bag, producing eggs ad libitum, apparently without the "bag" previously containing one, as the operator twisted it tightly together; also changing water into wine (an exquisitely finished performance) and transferring at will various articles from one box to another. Besides all these, a number of other capital tricks, which our space will not permit us to particularise, were performed in a most skilful manner. The only fault we had to find with the professor was a certain slight nervousness of manner, but as this has doubtless arisen from his lengthened absence from before an audience, it will in all likelihood soon vanish. We most heartily congratulate the men of the 1st Royals on possessing so clever a delineator of the mysteries of lergdemain [sic.] amongst them, as B. Hennessy, whom we will term "The Wizard of China", and we hope, if he should perform before other regiments in the Camp, as believe he intends doing on receiving the necessary and kind permission of the authorities, that he will receive the large amount of patronage which he so thoroughly deserves."

Hennicke leaflet c.1888 Page 1

Hennicke leaflet c.1888 Page 3

Hennicke leaflet c.1888 Page 4

REFERENCES:-

With thanks to Paula Nevin, great-granddaughter of Bryan Hennessy.

(1) sic. – should be Sir Hercules Robinson, Governor from 1859-1865, though there was later a Governor W. Robinson. General Sir John Lysaght Pennefather GCB, a veteran of the Crimea, commanded the Aldershot Home Command from 1860-1865. A search of Crimean Casualty Rolls (1854-1856) http://www.britishmedals.us/files/crimgi.htm does not disclose any entry for a B. Hennessy.

(3) Madame Lancia was not the same person as the British operatic performer, Madame Florence Lancia.

(4) Sydney Mechanics’ School of Arts, originally at 275, now 280 Pitt Street Sydney, was founded in 1833 and continues to perform its function as a lending library and source of education, cultural activity and vocational training for working people. https://smsa.org.au/about/ The original building is now the Arthouse Hotel, and for many years was the home of Will Andrade’s play, magic and theatrical shop.

(5) Bernard Reid, “Conjurors, Cardsharps and Conmen”

(8) Kipling’s diary has been published in the book “Something of Myself and Other Autobiographical Writings” edited by Thomas Pinney

(9) Gibeciѐre, a journal of historical research about magic. Vol. 3 No.2 (Summer 2008) published by Stephen Minch

(10) The illusion of "The Cherubs in the Air" is described by H.B. Wilton in "The Somatic Conjuror", Melbourne 1870. However, the apparatus required, along the lines of other "bodyless heads" such as the Sphinx illusion, would have been far beyond the capacity of an amateur magician in a non-theatrical setting.