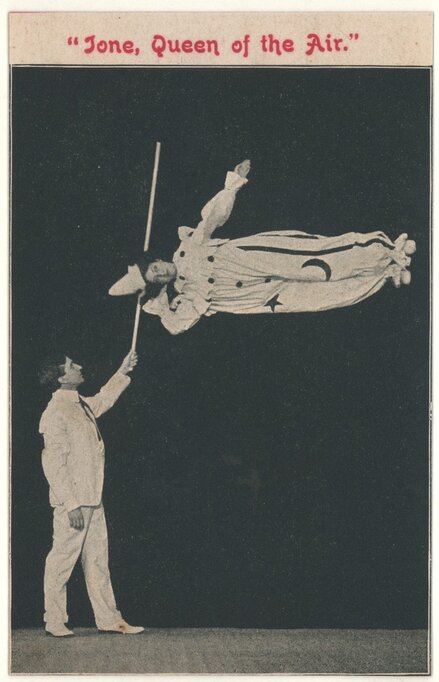

Ione, Queen of the Air

The story of Richard Bartholomew Smith and Howard Thurston’s Floating Lady

To the average theatre-goer, the magician’s famous illusion of the “Floating Lady” is just a single magical effect, one impressive feat of magic in the repertoire of stage conjurors for time immemorial. The reality is that the Floating Lady is scarcely more than 150 years old, and there are multiple, evolutionary, versions of the illusion, going by such exotic titles as Trilby, Aga, Astarte, Amazement, Asrah, Princess Karnac, and the subject of this story, “Ione”.

The history of the floating lady, first developed from a static ‘suspension’ of a person in the air into a mysterious spectacle in which the assistant rises into the air, sometimes rotates, and may even disappear in mid-air, is full of competing claims, cross-overs in technique, independent invention, and outright treachery and theft, well documented elsewhere, but beyond the scope of this story.

Here we try to shed some new light on one very small aspect of the levitation’s history. So, a caution that the tale of R.B. Smith and his invention goes into a depth of detail which may be beyond the interest of the casual reader.

Setting the Stage – Ione at the Palace Theatre, Sydney

W.G. Alma Conjuring Collection, State Library of Victoria

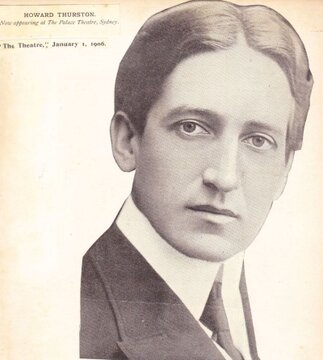

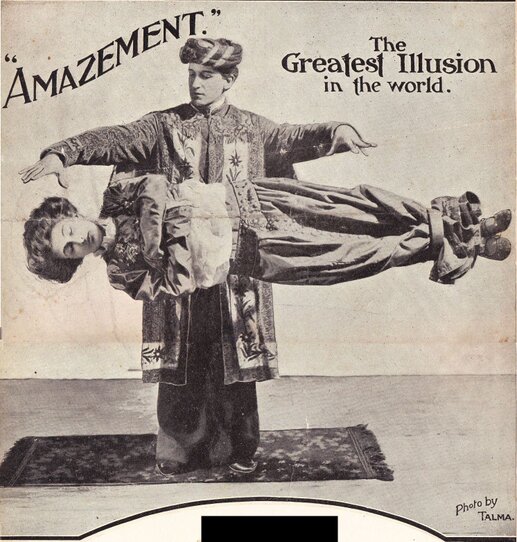

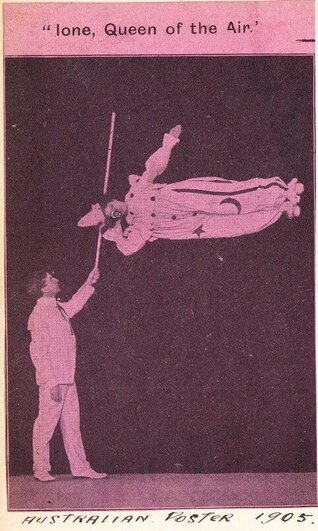

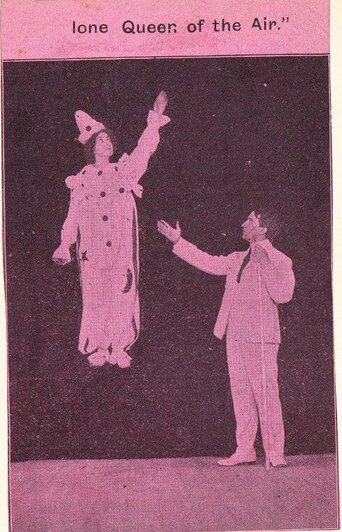

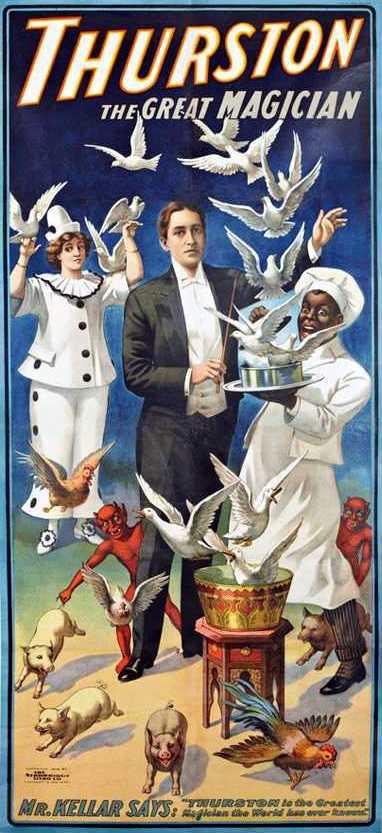

In mid-July 1905, up-and-coming American illusionist Howard Thurston arrived in Australia to open at the Palace Theatre, Sydney. Meeting with great success, he toured major Australian cities until March 13, 1906. Featured amongst his advertised thirteen tons of illusions was one named “IONE – Queen of the Air”.

A female assistant, dressed in a bright white Pierrette costume, stands on a small step on the stage, and is seen to rise into the air, the magician meantime waving a long pole around her body to show the absence of any physical connections. She then proceeds to revolve upwards and in a head-over-heels loop, her body also rotating in a sideways motion.

Thurston, proclaimed an American poster showing photographs of “Ione” in progress, “… is the Originator, Inventor and Maker of every illusion he presents.” In fact, the illusion’s mechanism was the invention of an Australian, Richard Bartholomew Smith of Sydney. The story which follows is more about Richard Smith than Howard Thurston.(1)

The Main Players

Richard Bartholomew Smith

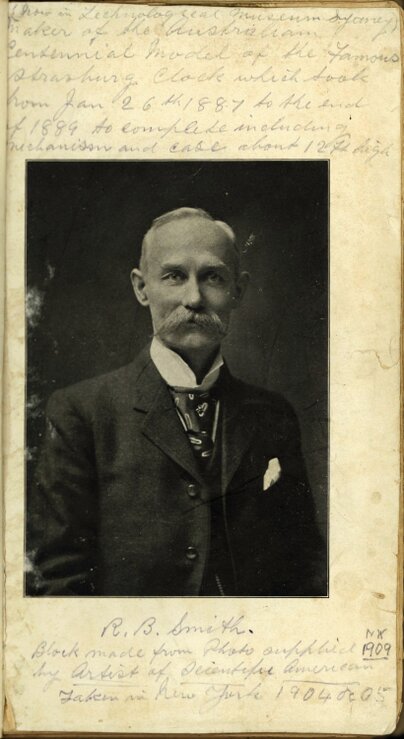

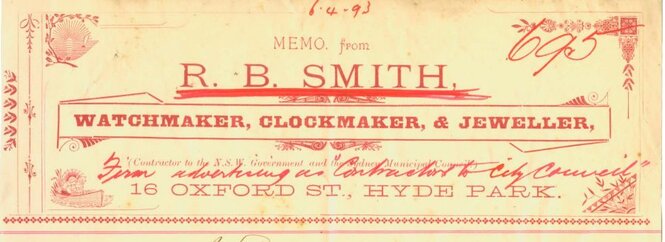

Richard B. Smith (1862-1942) has a significant claim to fame in the history of Sydney. Born at 84 Old South Head Road, on June 3, 1862 (2) he was a watch and clock maker, mostly based at 16 Oxford Street Darlinghurst (3), barely a step away from where Cec Cook would later, in 1961, open his magic shop at number 14A. His father was a fruit seller, but little is known of Smith’s schooling. His family history is expanded in reference note (17). How did a greengrocer's son acquire the delicate skills of watchmaking? Some newspapers made mention that he was “entirely self-taught”. However, in an article written by himself in 1917, Smith said, "... About that time I met one of the best watchmakers in Sydney. He agreed to teach me the watchmaking at night. I put in about two years from 7 p.m. to 11 p.m. with him. I gained a thorough knowledge of watches and some of the most intricate mechanisms ... When I was 22 years of age [ie, 1884] I started business at No. 16 Oxford St." (18)

Smith was by all accounts an enigmatic and somewhat difficult personality, but a creative and mechanically inventive man whose interests led in many different directions. Professionally his work included many public turret clock installations, as a contractor for the NSW Public Works Department; including clocks erected in the 1880s and 1890s at Broken Hill (4), Cootamundra, Redfern, Bowral, Ballina, Kempsey, Picton , Tenterfield and Newtown. On a smaller scale, the Powerhouse Museum holds a Skeleton clock intended for use as a timed switching device. (See https://collection.maas.museum/object/237784 )

Portrait of R.B.Smith in 1904 (13)

Collection: Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences. Photographer unknown.

Used with permission

As an inventor, Richard Smith created numerous devices stemming from his clock making skills. A search of patent records (5) and advertising reveals that he designed:

- A shadow clock which threw a beam of light containing the shadow of a working clock onto the pavement, or on a bedroom ceiling.

- A number of ‘sound reproducers’, for use with early phonographic records.

- Automatic “stop” devices for gramophones, and an automatic time switch for electric circuits.

- A ‘grandfona’ which played six records in sequence.

- A prototype ‘Safety Theatrical Chair’ with reclining mechanism (5)

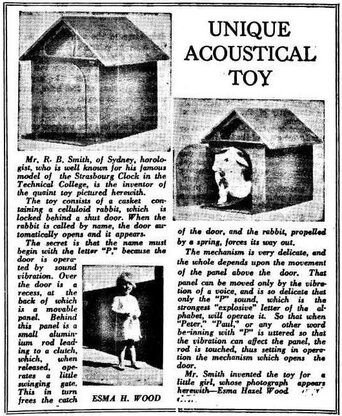

- A clever toy invented for a little girl, by which a rabbit emerges from a house when its name is called.

However, Smith’s magnum opus was created when he was in his mid-twenties. From 1887-1889 he spent all his spare time in the construction of a replica of the giant Astronomical Clock of Strasbourg Cathedral in France. Guided by little more than a photograph, a description in a book, and possibly having seen an earlier model on display in Sydney, Smith created the movements for multiple moving figurines including “procession of the Apostles”, “the Four Ages of Man” and a new “heathen deity” for each day of the week, together with dials showing the current phase of the moon and the rise & fall of tides, a geared display of the orbit of the planets, a dial showing local Sydney time, six other times in major world cities, moving mechanical cherubs, and a working depiction of the cycles of the Sun and Moon.

This extraordinary clock, with casings made by local artisans, was offered as a “Centenary Clock” to a rather bemused state government. After negotiations, the clock was purchased in 1890 for £700, and was installed in the then “Technological, Industrial and Sanitary Museum” housed in a dilapidated shed in the Sydney Domain. Immediately, the previous poor attendance at the museum started to increase, and since that time the clock has been a permanent and popular attraction at the Technological museum located in Harris Street , and now resides in a dedicated alcove at the Powerhouse (Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences), where it gives hourly displays.

For more detail on the clock (Strasburg, following the old spelling), see https://collection.maas.museum/object/180798

Richard Smith, having created his masterpiece, then wanted some of the limelight and began to show a side of his personality that was insistent, argumentative and, at times, bordering on mild paranoia. He would argue in later years that £700 had been poor recompense for the effort spent on the clock and, having been hired to maintain its workings and to lecture to the public for many years, he became something of a thorn in the side of museum directors, withdrawing the clock for extended periods of maintenance, and chiding the museum on their lack of understanding of his creation.

The complex mechanism was kept working despite regular problems, but finally in 1980 the Strasburg Clock underwent a major restoration of its mechanics, base and casework, which were filthy and threatening to collapse. To preserve the clockwork, the central turret is now operated electrically; it continues to provide visitors to Sydney with an impressive spectacle, and is a lasting tribute to R.B. Smith.

R. B. Smith demonstrates his Strasburg Clock, March 24, 1933.

National Library of Australia, at http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-162569281/view

Howard Thurston

Howard Franklin Thurston (1869 – 1936) should scarcely need an introduction, though the book, “The Last Greatest Magician in the World” by Jim Steinmeyer (6) is a great place to learn more. Freeing himself from a rather dubious existence as a youth, he had paid his dues and morphed into a skilled manipulator of cards on the Vaudeville stage, developed a huge illusion show which travelled the world, was named successor to the great Harry Kellar and was, during the heyday of Vaudeville in the 1920s, unquestionably America’s most famous magician.

While in his early 30s, Thurston spent eight months in England building his first big illusion show, opening in London, December 1902.

His journey to Australia in 1905 was almost derailed by the shyster entrepreneur, Maurice Bertram Curtis, who had, just a few years earlier, battled magician Oscar “Dante” Eliason in court over his Australian tour. Curtis, it turned out, had deceived Thurston over his bookings in Sydney, leaving him in a position of having to borrow money to travel to Australia laden with what he claimed was tons of equipment, fourteen assistants, a hastily arranged contract with George Musgrove, plus his talent and high hopes.

While in Australia, Thurston certainly had new equipment built for him by Claude Guest, a magician from Melbourne who performed a pseudo-Chinese act under the title 'Wong Toy Sun.' Thurston later wrote him a letter: "Dear Mr. Guest, It was a pleasurable surprise to me when I came to Melbourne to find that I was able to obtain in this country magical apparatus of intricate nature and elaborate finish. The orders that I have placed in your hands have been executed in the most perfect manner and have given me complete satisfaction. Wishing you every success, faithfully yours, Howard Thurston."

While in Australia, Thurston certainly had new equipment built for him by Claude Guest, a magician from Melbourne who performed a pseudo-Chinese act under the title 'Wong Toy Sun.' Thurston later wrote him a letter: "Dear Mr. Guest, It was a pleasurable surprise to me when I came to Melbourne to find that I was able to obtain in this country magical apparatus of intricate nature and elaborate finish. The orders that I have placed in your hands have been executed in the most perfect manner and have given me complete satisfaction. Wishing you every success, faithfully yours, Howard Thurston."

Upon his arrival Thurston opened at the Palace Theatre, Sydney on July 22, 1905 and never looked back. Touring the major cities with great success, he remained in Australia until March 13, 1906, before continuing on his world tour.

Smith in America - The Creation of “Ione, Queen of the Air”

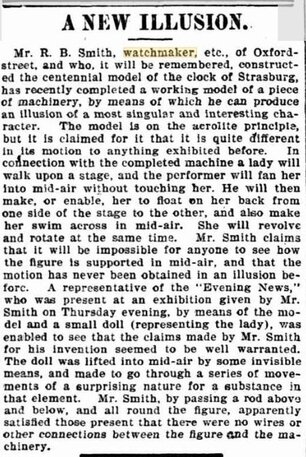

The first indication we have that R. B. Smith was working on the creation of a stage illusion comes on February 9, 1901 in a report from Sydney’s “Evening News”, which accurately describes the effect of the illusion in which “the performer will fan [the assistant] into the air without touching her … she will revolve and rotate at the same time”.

Evening News February 9, 1901

The article refers to a working model of the illusion being demonstrated, and this is confirmed by the notes of Australian magician Harrie Ensor (see transcription of his notes, at the end of this story). Harrie Ensor kept a notebook labelled “Births & Deaths of Magicians” in which he details a direct conversation held with Richard Smith, presumably post-1913.

Those notes mention that Smith had started creating “Ione” in 1900. Court magician, Charles Bertram, apparently viewed a demonstration in 1901 and was impressed, but lacked the funds to add the trick to his show.

Smith’s personal life is little documented, but in an interview with his granddaughter [see The Australiana Society Newsletter at reference (1)] it was recorded that he married Kathleen Downs - (however the correct name is believed to be Catherine Down) around 1882, and had four children, two boys and two girls, in eight years, though the marriage may not have lasted. On January 1, 1902, the New South Wales Police Gazette published a paragraph:

“Missing Friends – Left her home, Bourke-Street, next the ‘Clippers Arms Hotel’ on the 18th ultimo, Ruby Smith, 14 years of age, medium height and build, dark-brown hair, large blue eyes, fresh rosy complexion; wore a sailor hat and tan boots. Supposed to have been taken away by her grandmother, Mrs. Jacobson, of Young-street, Annandale. Information to her father, R.B.Smith, watchmaker, 114A, Oxford-street."

Whether or not family breakdowns impelled Richard Smith to make a change, or whether he had simply formed a view ( as he later stated) that his inventive skills were not being properly recognised in Australia, he decided to pack up and move to the United States, with the goal of marketing his inventions. According to Harrie Ensor’s notes, this was about August 1903. He took the working model of ‘Ione’ with him. He showed the model to Thurston, who had returned from Britain and was in the process of evaluating his show following a tour of the US mid-west. According to Smith, an arrangement was made to pay an initial sum for use of the illusion, and then to pay £200 further money out of the proceeds of showing.

Smith was to remain in America until 1913. His time there is documented by a few letters he sent to the Australian newspapers. He clearly made some kind of a living to support himself for ten years. Unfortunately the facts are hard to confirm, as Smith not only had a tendency to make claims which others have found dubious, such as having worked for the prestigious firm of Tiffany’s & Co for eighteen months, or being offered work by Thomas Edison; but also because Smith’s exaggerated sense of being persecuted led him to make some extraordinary claims about being pursued, harassed and poisoned by a supposed “gang” in New York. [see the full transcript from The Evening News, October 30, 1913, at the end of this story]

However it certainly appears that he made a tour of the Edison factory in Orange, New Jersey (7) and demonstrated his invention for enhancing the sound pickup from gramophone records (which he would later accuse Edison of pilfering).

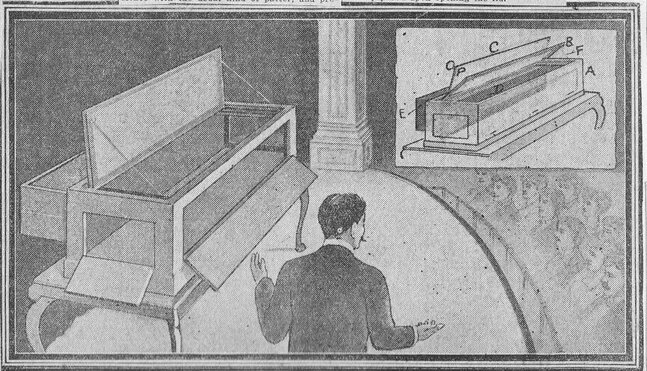

There are other indications that Richard Smith was interested in inventing magical illusions for the stage. Scientific American published a story detailing a “Casket Illusion” (8). The effect was that a long box was shown empty by opening doors in the top and front, and a woman would then appear in the box. Mechanically, the device operated by a series of ropes and pulleys which drew the assistant behind the box as the doors were opened, and delivered her back into the box when the doors were closed. It appears that the article was based on a working model, and probably never became a fully-realised prop. From a magician’s point of view the idea is lacking in magical interest, and is too complex to be worth considering (a “tip-over” trunk would achieve the same effect without the mechanics).

The Casket Illusion, described in The World’s News, October 14, 1911,

and photographs of Smith’s model of the illusion - from the Ensor Scrapbooks, Volume 9/134

Also, in September 1905 (9) Smith made mention of a flying automobile illusion “… in which a lady is seated. The lady walks on to the stage with the auto, takes her seat; the performer commands both to rise into mid-air. Then the lady sets the wheels in motion; she travels across the stage, turns round, then travels to the other side, she then makes a turn up to the ceiling, travels along upside down, turns round, and travels backwards and forwards several times. Then she loops the air, making many revolutions in the air while travelling from one side of the stage to the other; then forms an elliptic in the air. She then approaches to the centre, still in the air; that lady leaves the auto, walks to the right while the auto travels to the left. They both make a turn at each side up the stage, and meet in the centre, where the lady resumes her seat and goes through a number of evolutions before descending to the stage.”

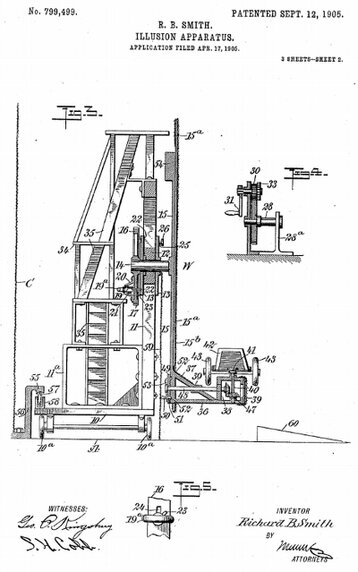

Smith claimed he would make arrangements to show the automobile illusion himself on the stage, but whether this invention was ever more than a design cannot be confirmed. An application number 799,499 mentioned by Scientific American proves to be the full patent application for the flying car illusion, which is even more cumbersome than "Ione" and uses Smith's forte, giant cog wheels. See Reference 16 for a link to the patent application.

The same article referred to Smith’s claim of being the inventor of the illusion, “Ione”, recently shown at the Palace Theatre, Sydney, “… and legal proceedings in connection with it are pending.”

Three Levitation Illusions

Before continuing, it is helpful to first review several “floating lady” illusions which relate to the story.

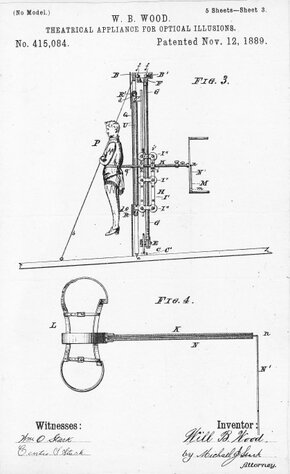

Astarte – was the Middle Eastern goddess of war and sexual love. The illusion was created originally under the title “Edna” by Will B. Wood, who applied for a patent in 1889 (11). This early levitation illusion was enhanced by William Robinson (later known as Chung Ling Soo) and Benjamin B. Keyes. It was seen first in Harry Kellar’s show, and later in Alexander Herrmann’s as “The Maid of the Moon” or “Florine”. Magician Harry Carmo later performed the illusion as “The Mummy”, and it has been seen in modern times, in a number of performances which are probably best described as ‘historical recreations’ including a presentation by illusion creator John Gaughan at the Conference on Magic History.

In performance, an assistant faces the audience and is seen to be floating in the air. She makes various revolutions in the air, spinning both sideways and lengthwise, and in some presentations having the ability to move left and right across the stage.

The illusion can be viewed in these two examples, by Jeffrey Atkins and Doug Henning

The clever but complex mechanism can be inspected at Will B. Wood’s patent application, https://patents.google.com/patent/US415084

Amazement - Howard Thurston presented, in the same season as “Ione”, his version of the standard “Aga” levitation. Standing on stage dressed in an Eastern outfit, Thurston caused his assistant to rise from what is often described as a “low coffin” box, floating horizontally up into the air. By means of an addition from the mechanics of the “Astarte” illusion, Thurston was then able to make his assistant revolve sideways into a face-down position, and back. Thurston named this illusion “Amazement” and it was to receive the most attention of all the illusions in his show, short of the “Creation” or “Dida” illusion in which an assistant materialised in a tank of water.

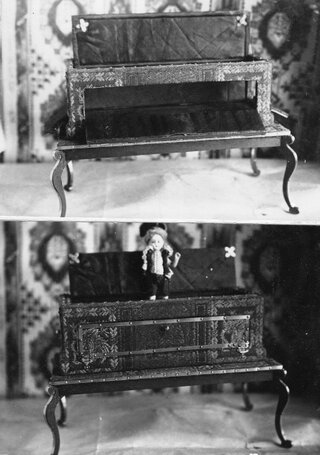

Ione - The subject of this story. The title “Ione” came from the name of a sea nymph in Greek mythology. In performance, the girl was hardly dressed as a nymph, but was attired in a bright white Pierrette costume for contrast with the pitch-black background against which she performed.

She started by standing on a small step then, in a similar effect to “Astarte”, the assistant floated up in the air, and was able to rotate sideways along the axis from her head to feet, and also in large revolutions head-over-heels; these two actions taking place simultaneously. The magician waved a long pole around the assistant to demonstrate her apparent lack of connection to any mechanism.

The actual mechanics of the illusion were quite different to those of “Astarte”, and will be dealt with later in the story. Not mentioned in most reports, but related in the court proceedings of early 1905, is the fact that the illusion took place in a large black cabinet shape, designed to create a flat black surround which was necessary to the performance.

Two views of the Ione illusion from parts of a poster in the ‘Ensor Scrapbooks’

The Court Case – April 1905

Australian newspapers, in a syndicated story of April 1905 and before Thurston travelled to Australia (10), reported that R.B. Smith had taken Howard Thurston to court in pursuit of money owing to him for the rights to use “Ione”.

This transcript is from the Macleay Chronicle April 27, 1905:

R.B. Smith in America

Mr. R. B. Smith (late of Oxford-Street, Sydney), who put up the clock, went to America about two years ago for the purpose of disposing of several mechanical illusions, which he had invented. According to the New York World , Mr. R. B. Smith recently appeared before the Sixth District Municipal Court of New York, with a claim against one Howard Thurston, for the use of a mechanical illusion known as “Ione, Queen of the Air.” The claim was for 500 dollars (£100), for the use of the invention.

In the illusion, “Ione” appears before the audience, clad entirely in white. Then she enters a cabinet, the sides and back of which are jet black. Standing in the centre of the cabinet, she gradually rises turns to the right and left, gracefully waves her hands and feet, and apparently glides through space at will.

Judge Koesch and the spectators in his court were nonplussed as they listened to the many wonderful things that the “King of Magicians” was able to make “Ione” do. They breathed a sigh of relief when the inventor explained the mechanics of the invention, and remarked, “how simple!”

Inventor Smith explained that the cabinet is so arranged that not a ray of light pierces the interior. Concealed in the floor is a disc on which is an invisible platform. “Ione” steps upon this platform and from behind a steel rod is fastened to an iron belt that encircles her waist. Then a man under the stage turns a crank, and her body is gradually lifted into space. A second crank, worked by a man dressed entirely in black, and concealed in the cabinet, make the “Queen of the Air” revolve at will.

According to an understanding between Smith and Thurston, the former was to receive $1,000dol. for the idea. He alleges that only 100dol. has been paid him so far. Thurston had testified that the machinery had cost him so much more to build than he expected that he did not think the inventor was entitled to more money. “Anyway, it’s not so wonderful,” he added.

“Well, why do you bill it as the most wonderful illusion in the world,” asked counsel for Smith.

“Because I had my paper printed that way.”

“This whole proceeding is an illusion to me,” announced the judge. “I’ll reserve decision until I have studied it out.”

From Harrie Ensor’s notes, made in discussion with R.B.Smith in later years, it seems that the American court found that it had no power to order any further payment, since the written agreement referred to further moneys being dependent on “moneys from showing that could be agreed upon themselves.” Since the parties could not agree, the payment could not be enforced, and Smith was left lamenting.

At right - This poster, featuring the Duck Tabouret, appears to show the Pierette costume originally worn by the floating lady from the Ione illusion. The poster dates to about 1908, when an earlier version shows Kellar and Thurston's images at the top, with the header "Kellar's Successor, Thurston."

Thurston’s Performances of Ione in Australia

Howard Thurston was known to be on a continual search for different and better illusions, frequently rejecting or discarding existing and very workable tricks from his repertoire. Illusion inventor Guy Jarrett spent many lines of text bad-mouthing Thurston in his book “Jarrett Magic" (1936) but it has to be admitted that Thurston had the showman’s sense of knowing what would work for his audiences, and his stellar success as America’s foremost illusionist cannot be overlooked.

On that basis, one needs to query why he felt it necessary, or even desirable, to include two levitation illusions, Amazement and Ione, in the same evening show – Ione in Part Two, and Amazement in Part Three. Why, also, would he have chosen to spend time and money attempting to perfect “Ione”, when the “Astarte” illusion had a very similar appearance to the audience, and had already been in existence for over fifteen years? Looking at the videos of Astarte, and the mechanics of Ione, they can be seen as mechanical marvels, but certainly not wholly successful in creating the full illusion of effortless flight. Astarte displays a certain "slip and bounce” which detracts from the magic, and Ione gives the impression that it would be a very rigid and mechanical effect to an audience.

In recent years, the levitation has been smoothed out and is nowadays performed in the version known as “Asrah” (Servais Le Roy’s invention), where the assistant vanishes after floating; a simpler method and far more magical. David Copperfield’s presentation of “Flying” may be the most convincing and truly magical version of self-levitation ever devised, but sadly reproduced by some other performers who have done no favours to the illusion.

Charles Waller in his book ‘Magical Nights at the Theatre’, states that when Thurston arrived in Sydney in 1905, he was “broke, but I think that to make a good story, he exaggerated his condition …. Arriving with insufficient material for a full night show, he was compelled to spend several weeks in the construction of additional illusions.” Interestingly, Waller makes no mention of the performance of “Ione” whatever, and since he viewed the Melbourne season, it has to be questioned whether Ione had, by this stage, been dropped from the show altogether.

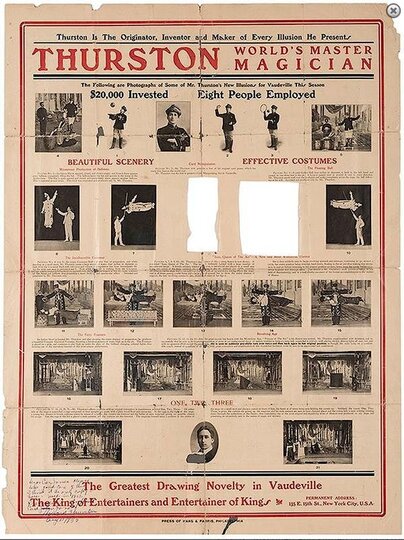

Thurston had, prior to 1905, issued a poster with photographs of numerous of his illusions and a description of the effects, showing five images of Ione in progress (11). The poster states “the following are Photographs of some of Mr.Thurston’s New Illusions for Vaudeville This Season’.

There is no doubt that Ione was performed at the start of the 1905 Sydney season. It is listed in advertisements for the opening on July 22, and is mentioned in a review from July 24. However, while the “Amazement” levitation received several sentences of description, Ione was relegated to merely, “Other illusions which caused amazement were “Ione, Queen of the Air”, the Human Hennery (in which Thurston produces numerous eggs ….[etc.]”

Unfortunately, because there were two levitations in the show, and because newspapers often did not give as much description as a researcher might wish, it is not always clear whether a report is talking about Ione or Amazement; but it does seem that while Amazement continued to draw attention, “Ione” fades quickly from sight and, one suspects, was dropped from the show very early in Thurston’s season. On a curious note, very few reports of “Amazement” make any reference to the girl rotating, and it might be questioned whether the mechanism was proving unreliable and had to be confined to raising the girl into the air.

If the illusion was dropped from the show, what happened to the apparatus? We don’t know. A photo of the Ione illusion was included in Thurston's 12-page promotional brochure c.1908 (14) though there is no evidence that he was performing it at this date.

Close to Thurston's tour, illusionist Charles Stutley (stage name 'Breton') was advertising a levitation also under the title "Queen of the Air". However photos exist to show that it was not the Ione prop, and historian Harrie Ensor wrote (15) that although Breton had seen the Thurston version of "Amazement", he acquired a self-rising and revolving suspension originally built for Alfred Silvester, son of the Fakir of Oolu, in 1904.

A tantalising news article of 1905 (19) suggested that Thurston's shyster manager, M.B. Curtis, had presented Ione in New Zealand (to which country Thurston never travelled); but when hunted down, Curtis' magician proves to have been the Australian Clive O'Hara a.k.a. Henry Clive, and he was presenting the standard Aga levitation.

Historian Robert E. Olson, in his book “The World’s Greatest Magician – A Tribute to Howard Thurston” relates this telling story, though no source is given:

“Illusions must be well constructed”

Illusions for this reason must be sturdy and foolproof for safety reasons. IONE, the trick where a girl revolved in mid-air, caused what could have been a serious accident in the early Thurston act. The girl was about to revolve when she shot forward and fell head first ten feet to the stage. The girl fell because she had not been properly fastened to the equipment. She got to her feet in a dazed condition. Fortunately she was not badly hurt. They stepped through the curtain, the girl holding Thurston’s arm, walked to the footlights and she took her bow. The audience gave her a good hand, being reassured that she was alright.”

(One might comment that the good construction of the illusion was less in question than the care with which the assistant was fastened into her equipment!)

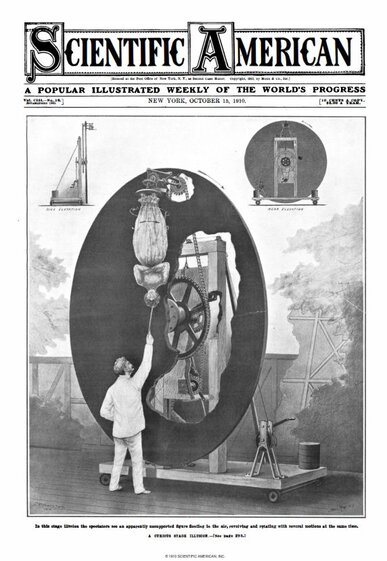

Ione in the ‘Scientific American’

Finally we come to the workings of the Ione illusion. Richard Smith, in his Evening News report of October 1913, mentioned that the proprietors of the Scientific American magazine had been very supportive.

On the front cover of the Scientific American, October 15, 1910, is a full page illustration of a huge mechanical contraption, showing a woman suspended upside down while a magician waves a stick around her body. This was the Ione illusion and, inside the magazine, a full column of text describes in detail the operation of the illusion, naming the inventor as “Robert” B. Smith. In all probability, R. B. Smith sold the magazine the rights to publish his invention in order to raise some much-needed money.

Ione in the Scientific American

The basic operation of the gearing and rotation is clear from a brief examination of the diagram, but overall the illusion looks cumbersome and stiff, as though the assistant was the hand on a giant clock face, which effectively she was.

Again, as a mechanical marvel this was a clever invention, but it does not appear to be something which a magician can easily “sell” to his audience as a miracle.

In the long history of floating women, all these versions were merely forerunners of later evolutionary improvements and completely new methods.

British magician John Neville Maskelyne’s incredible levitation was pilfered by the American Harry Kellar who, when he retired, sold it in 1907 with the rest of his show to Howard Thurston. Although heavily criticised for the way in which he exposed the secret to some of his audience, Thurston would go on to make “The Levitation of Princess Karnac” one of his most famous and successful feats, remaining in his big show for many years.

Minor Players and a Final Puzzle

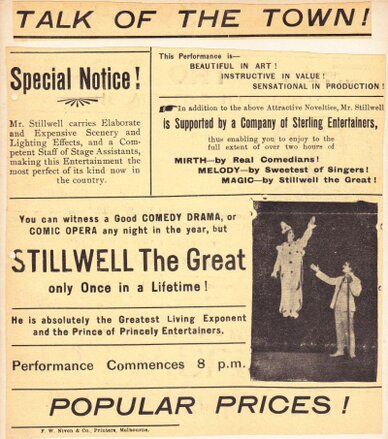

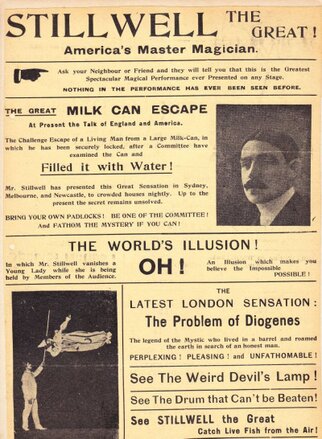

George Stillwell -

As supporting acts, Howard Thurston had featured coin manipulator Allan Shaw and, in his South Australian season in Adelaide, George Stillwell (c.1874-1934), famous for his silk handkerchief act.

From the Ensor Scrapbooks, Vol.10

Stillwell had come to Australia via New Zealand in mid-1905, and became a virtual resident, living in Sydney and Melbourne; he was still in Australia as late as March 1912. In South Africa, had married an Australian wife, comedienne Elsie Forrest (June 1903). By October 1905 he was working as a support act with Thurston in Adelaide and continued with him until 1906. In August 1908 he was presenting the illusion called “Oh!” (a test-conditions vanishing lady) at Moore Street (now Martin Place) in Sydney. He worked at Albert’s Music Store around 1909 when not performing. In 1911 he was reportedly running a big illusion show, “but only performs occasionally” [Ensor scrapbooks vol.8 p112] Stillwell died at Samarang Hospital in Indonesia on July 17, 1933.

The slight mystery is a partial playbill or brochure in the Harrie Ensor scrapbooks, presumably from around 1908 when he was performing “Oh!” Featured are two photographs of a performer presenting the “Ione” illusion … but on closer inspection they prove to be the original photos of Howard Thurston, to which a moustache has been added! There is no text mentioning the illusion.

Oscar “Dante the Great” Eliason and the Automaton – Oscar Eliason, who caused a furore with his tours of 1898-1899, featured an illusion called the “Marvellous Bicyclist” wherein his wife and assistant, Edmunda rode a bicycle onto the stage and up into the air. Before the cycle returned to earth it performed astonishing manoeuvres, at one stage leaving the rider upside down beneath the cycle. Speculatively it might be thought that this was some version of the ‘Astarte’ illusion.

Thurston was made very well aware of Eliason’s fame in Australia, where he had died in a shooting accident in 1899. After visiting his grave, Thurston kept the name “Dante” in his mind and, many years later, bestowed it on magician Harry Jansen whose show grew to rival Thurston’s in spectacle and success.

Finally, to come full circle, the ‘Ensor scrapbooks’ have two portrait photographs of Oscar Eliason, and a handwritten note by Ensor, “purchased from R.B. Smith, Oxford St Sydney”. It is apparent that Smith either knew Eliason or was inspired by his artistry, for in 1903 he created a mechanical figurine which performed several of Dante’s best-known tricks:

Evening News (Sydney) - April 4, 1903 - Clever Mechanical Model:-

"The mystic doings of Dante the Great, of delightful memory, have been most artistically perpetuated by Mr. R.B. Smith, who has gained deserved notoriety as a manufacturer of marvellous creations in clock work, among which may be mentioned the famous Strasburg clock. Mr. Smith has just completed for Mr. L[aurence] F[rancis] Fitzgerald, of the Crystal Palace Hotel, George-street, near the Redfern Railway Station, a remarkable piece of mechanism. Upon a mimic stage stands a figure, representing the late Dante, and by the aid of the clever arrangements of levers and skilfully-designed contrivances some of the famous conjurer's best tricks are reproduced, principal among them being that causing named cards to rise on a table at the word of command. The head of the figure has been fashioned from a model taken shortly before the unfortunate incident which robbed the amusement-loving public of the skilful performer.

There are over 500 pieces in the work, and 37 actions are gone through, the performance lasting about eight minutes. Another trick reproduced is that of the wine bottle, with the alteration that in the case of the model, a flower pot falls over, and through the part of the stage upon which it stood a bottle of Mr. Fitzgerald's famous King Whisky rises to view. The clever mechanical production, upon which more than 450 hours of labour were expended, and which will be delivered to Mr. Fitzgerald this afternoon, is operated by a water motor. Mr. Smith has been congratulated upon this clever example of his craftmanship."Conclusion

Richard Bartholomew Smith was a complex, driven, and enigmatic character. His undoubted mechanical genius was somewhat unrewarded and his magical inventions probably lacked the magic touch required to be completely successful.

But every hour, for a hundred years and more, Smith’s Strasburg Clock, and his clocks around the state, have chimed in tribute to a fascinating Australian inventor, and his treasured illusion, “Ione” was performed by The World’s Greatest Magician.

REFERENCES and Extended Notes

Harrie Ensor – transcription of a direct discussion between Ensor and Richard Smith, sometime post-1913. Recorded in Ensor’s notebook “Births & Deaths of Magicians”:

Richard B. Smith

Born 84 Old South Head Rd Sydney NSW Australia (now Oxford Street).

Born 23rd June 1862. [However his birth announcement of June 14 shows as 'June 3']

In 1900 invented “IONE” or Queen of the Air – Made a working model – still in his possession time of death – offered it to me for £5. When Chas Bertram was at Palace Theatre 1901 he viewed working of model. Bertram was pleased but not having purchasing money £200 in hand had to refuse same. In 1903 Smith went to America about August 1903. He took working model with him, also specifications. He showed model to Thurston & arranged to pay £200 further money out of the proceeds of showing. Thurston [unclear – ‘pulls’?] over Smith as the agreement read $200 (£40). Smith brought the matter to the American Courts of law the magistrate found that he had no power to alter – owing to agreement [interpolated comment: ‘Smith when in America stopped at the Occidental Hotel on the Bowery’] … with Thurston read inter alia: “I pay RB Smith the sum of $200 & further moneys from showing that could be agreed upon themselves.” The American court found that it had no power over further money. That that had to be agreed upon among themselves. Smith & Thurston.

Thurston made good money with the illusion & when he came to Australia 1905-6 brought & showed same here. But he was preceded by a letter to the Sydney Morning Herald, explaining full facts of the illusion from Smith & was forced to acknowledge R. B. Smith the inventor. [Author’s Note: this cannot be found, but the Evening News of October 1905 makes these claims, and earlier reports of the court case exist in April1905]. Smith stayed in America 1903-1913. Copies of Scientific American between these dates showed [unclear] illusions of his – “The Casket” & others. He invented the [amber?] in phonographic record. Some sold to Douglas Phonographic Co. (John [Kaiser?]) $2000. Particulars from Smith personally.

====================

Transcript of The Evening News, Thursday October 30, 1913

A SYDNEY INVENTOR

HIS EXPERIENCES ABROAD

OPERATIONS OF THE “GANG”

MR. R. B. SMITH’S ADVENTURES

Mr. R. B. Smith, whose high reputation as an Australian inventor has led him into many perilous situations, told an “Evening News” reporter this morning of his interesting experiences while away from this country, to which he has just returned after an absence of more than ten years.

When Mr. Smith left Sydney on July 27 1903, to seek new fields of wider scope for his inventive genius, which among other things, had given to Sydney the only existing replica of the Strassburg (Alsace) Clock of the Twelve Apostles, he little imagined that ten years later would find him retracing his steps, a man wealthy in thrilling experiences, but lighter in pocket.

But Mr. Smith’s story, as told by himself, is worth repeating verbatim.

“I left Sydney a little over ten years ago, and I have come back, back to stay. Not only because I have met with most discouraging experiences, but also because there is, after all, no other city that can compare with ours for beauty, and above all that inspiring hospitality which makes all within its gates dear friends. I was headed for America, the land of dreams of every man whose own country seems to offer him no opportunities. I went to New York and there was offered 13s a day by Thomas Alva Edison, but I refused it because I thought I could do better elsewhere. I wish I had accepted it, for that would have been some recompense for two of my inventions which the ‘great’ Edison appropriated, without saying so much as ‘by your leave.’

Well, there is no use crying over spilled milk, though it hurts to think about it. Next I applied to and received employment at Tiffany’s, the world’s greatest jewellers, and remained for 18 months in their clock department. By that time, I had completed some new inventions, and when I looked around for a moneyed man to assist me in their practical exploitation, I fell into the hands of commercial highwaymen – yes, that would be about the proper name to call them – and, to make a long story short, they not only got what little money I had, but they also swindled me out of my inventions, by means of a forged bill of sale, which they registered at the Patent Office at Washington D.C. Of course, there was no use fighting them. I did that for a short while, but I became soon convinced of the fallacy, for they belonged to the “gang” and I suppose I should consider myself lucky, indeed, that they did not get my life in the bargain.

From that time on my troubles started. Through what manners and measure of persecution I went at the hands of the gang, is almost beyond belief. Suffice it to say that they did not stop short of attempting several times to kidnap me, but more than twenty times they actually tried to get me out of the way by means of ingeniously hidden drugs in my food. They even went so far as to saturate eggs – they knew where I went for my supplies, with poisonous substances. Yes, they even tried to murder before they got away with Rosenthal, whose murder resulted in a world-wide scandal, and sent Lieutenant Becker, of the New York Police Department, to the death house in Sing-Sing. [Author’s Note: see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rosenthal_murder_case re the 1912 murder of a bookmaker by the ‘Lenox Avenue Gang.’ ]

Things finally went from bad to worse, and though Mr. F.C.Beach and Mr. Charles Allen, the proprietors of the “Scientific American”, gave me all the assistance, both morally and financially, that anybody could possibly expect from his fellow-man, I had to quit America after a struggle of ten years. What those ten years meant to me, crushed in proud hopes, ambitions, and fond dreams, no man will ever be able to realise, unless he went through the same discouraging experiences and adventures. Yes, they even robbed me of some magical illusions, among them ‘Ione’, the woman revolving and rotating in mid-air without apparent support, and the so-called casket illusion, causing the appearance and disappearance of a woman in a casket. ‘Ione’, by the way, was produced in Australia by Thurston.

Well, to get back to my departure from America for London. Even there the ‘gang’ followed me through their confederates in the Empire’s capital until I found myself reduced to seek the aid of Sir George Reid. The High Commissioner [treated me] most cordially and, had it not been for him and several other warm-hearted Australians I don’t think I would be here to-day.”

Mr. Smith brings with him several new invention, “but no plans”, he added, with a pleasant smile, through which shone determination and renewed hope, “except such plans as I can carry safely in my head.”

Mr. Smith sounds a strong note of warning to young and ambitious Australian inventors. “They should never enter New York”, he says, “as long as commercial highwaymen and the ‘gang’ are plying their nefarious trades. But please do not misunderstand me. I have nothing but the kindest regard and highest opinion for the real true American . There are no white and truer men than the real Americans, and I never wish to meet any better. But when you speak of Americans you must always discriminate between the native-born American and the white-washed specimen that becomes a stepson of Uncle Sam by way of the naturalisation courts. It is only the American by adoption who carries the Stars and Stripes on his sleeve and offers to ‘lick’ any many on sight for any alleged or imaginary disloyalty to ‘his’ country. The true American does not carry his patriotism on his sleeve; he carries it in his heart, and he knows nothing of that race hatred and national distinctions, stirred up and festered by his step-brother.”

A wonderfully ingenious clock, a shadow clock, whose secrets of construction have been published in the leading scientific journals of America and Europe, is another of Mr. Smith’s inventions that he is bringing to Sydney. He is now engaged in completing one of these marvellous timekeepers for President Roosevelt. When despatched to Colonel Roosevelt it will constitute a lasting advertisement for Australia in general, and Sydney in particular, as the inventor will equip it with fine views of the Commonwealth, and especially of Sydney and her beautiful harbour sights.

===================

References:

(1) Three documents giving a detailed history of the Strasburg Clock replica and some biographical details about R.B. Smith:-

https://australiana.org.au/magazine/article/?article=1976 - The Australiana Society Newsletter, article by Eve Stenning. The references to a Kathleen Downs appear to be slightly in error, as a search of marriage records in New South Wales lists a ‘Down, Cathr’ marrying Richard B Smith in 1881 (ref. 164.1881)

- Biographical notes at https://www.daao.org.au/bio/version_history/richard-bartholomew-smith/biography/?p=1&revision_no=11

(2) Australian magician, Harrie Ensor, was a history buff and collector. His large assemblage of historical clippings is my initial source for this story, and can be viewed in full on this site.

In addition, Ensor compiled a notebook titled ‘Births and Deaths of Magicians’, now owned by Peter Rodgers, in which he made notes on numerous magicians whom he knew personally. The details given for RB Smith’s birth are from this notebook, and came directly from conversation with Smith.

Further confirmation comes from the family Bible images held at the Powerhouse Museum, Sydney.

(3) From 1891-1893 Smith was in partnership with Henry Hansen. An 1893 bankruptcy brought his business partnership to and end though he continued in business on his own account and was discharged in 1895.

(5) Patent records at https://patents.google.com/?inventor=Richard+Bartholomew+Smith

Theatrical Chair at https://collection.maas.museum/object/237122 Safety Theatrical Chair

(6) “The Last Greatest Magician in the World” by Jim Steinmeyer. ISBN 978-1-58542-845-8, published by the Penguin Group, 2012

(7) Letter from R. B. Smith to the Sydney Morning Herald, November 16, 1904

(8) Details of the Casket Illusion, originally published in Scientific American, can be found at

(9) The flying automobile -

(10) For some reason, a year later, in 1906, the exact same story was printed in some Australian papers, as though it had just occurred. This is most unhelpful to the hapless researcher; the correct date was 1905, prior to Thurston travelling to Australia.

(11) A copy of Thurston’s poster showing ‘Ione’ is in the huge collection of Thurston memorabilia owned by Rory Feldman.

The image shown is a damaged copy sold at auction.

The Ensor scrapbooks contain clipped images on purple paper, which appear to have come from a similar poster. The annotation says “Poster 1905”.

(12) Stillwell’s routine is described in “Silken Sorcery” by Jean Hugard.

(13) Portrait of R.B.Smith bound in a book owned by the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences.

Used with permission

(14) The Complete Life of Howard Franklin Thurston, by Robert E. Olson, Volume 1 page 140. Hades Publications 1993 ISBN 0-921298-19-6

(15) 'Magical Reminiscences' by Harrie Ensor. Edited and published by Brian McCullagh, Sydney 2004.

(16) The patent application for Smith's "flying car illusion" can be viewed here

(17) Some notes on Richard Bartholomew Smiths ancestry: These notes originate from four rather indistinct images at the Powerhouse Museum website,

showing pages from the family Bible of Richard Bartholomew Smith. Additional newspaper research then adds to the detail.

Bartholomew Smith (Richard’s father) was 'born in the year of our Lord 1837 in the County of Cavan in Ireland. Came to Sydney in the ship Dublin in the year of 1849' [ record not located].

Bartholomew was a fruiterer (grocer) and bought his goods at the George Street Markets. In February 1871 he wrote a petition to the Mayor of Sydney, signed by many stallholders, complaining of the ‘arbitrary power exercised by Mr. Carruthers, Clerk of the markets’. [City of Sydney archives 26_107_127]

He died on May 11, 1890, aged 53 at his residence, 16 Oxford St, after a 'long and painful illness which he bore with Christian fortitude.' His death notice says he was a native of Coote Hill, County Cavan, Ireland. His burial was at Waverley Cemetery, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/218647834/bartholomew-smith which seems to be unmarked.

Catherine Smith (Richard’s mother) was born in year 1837 in County Monaghan in Ireland. Came to Sydney [18 or 12] May 1850. She was still alive in 1891 but her death record has not been located as yet.

Richard Bartholomew Smith’s siblings:

Mary Jane Smith was born on the 30th May 1867 at 84 South Head Road Sydney. Baptised at St. Mary’s Cathedral as were the other chilren. She married Edgar Ayres in 1901, had a daughter, Vera, and died in 1928. [Marriage record 2696/1901, New South Wales], and is buried at Waverley Cemetery in the same unmarked plot as her father.

Charles Edward Smith was born on the 4th November 1856 at Rushcutters Bay Sydney. He died 1867, less than 11 years old, "after a long and painful illness of three and a half" and his funeral was April 13, to Catholic Cemetery Petersham (Rookwood). The announcement mentions his father as 'Fruiterer and Greengrocer'.

William James Smith was born on the [23rd] May, 1859 at 84 South Head Road Sydney. He married Catherine Donnelly on Jan. 21 1880. He was living at 86 Oxford Street. They had a boy, also named William James, who died on February 27, 1888 aged 16 months. They were then at 19 Hart-Street Chippendale.

Walter Joseph Smith was born on the 25th [August?] 1864 at 84 South Head Road Sydney. He died April 23, 1907.

(18) Extract from a longer article, written by Smith, concerning the design of the Strasburg Clock:

The Newsletter: an Australian Paper for Australian People (Sydney, NSW : 1900 - 1919), Saturday 29 December 1917, page 6

It may not be out of place to relate first how I gained my knowledge in the art of mechanism without any tuition. The first machinery I ever saw was when I was a boy about 10 years of age. It was a small Yankee time-piece clock. The clock spring had broken and my father set to work to repair it. I watched him very intently. I made up my mind then that some day I would have the works of that clock to investigate...

... Eventually I got a position at T. Wallis and Co., a large manufacturing jewellery company, also importer of watches, clocks [note, this firm has not been identified in Sydney but was a large British concern, with possibly a branch in Sydney].

... the thought struck me if I bought a clock at wholesale price out of my wages and brought it home I could get the old clock... which I fitted the clockwork with a pair of paddle wheels. I set out one evening at dusk with another boy to the pond now called Kippax Lake in Moore Park, to start it or give it a trial trip. Everything went well until she got to the middle of the pond, when to my astonishment she turned turtle and disappeared.

... About that time I met one of the best watchmakers [whom Smith does not name] in Sydney. He agreed to teach me the watchmaking at night. I put in about two years from 7 p.m. to 11 p.m. with him. I gained a thorough knowledge of watches and some of the most intricate mechanisms including repeaters (watches that, chime the quarters and minutes on small steel gongs and chronographs).

... When I was 22 years of age [ie, 1884] I started business at No. 16 Oxford St. in which street I was born, then called South Head Road. I there made my first clock with a three feet dial and placed it over my door....

(19) The Newsletter, October 7, 1905:

"The other day The Newsletter had a paragraph about R. B. Smith, the whilom Oxford-street watchmaker, whose model of the Strasburg clock was such a big draw. Smith writes the Evening News to claim that he invented Ione, the illusion lately shown here by Thurston, and in New Zealand by Curtis ...."