Go To: Chapter One |

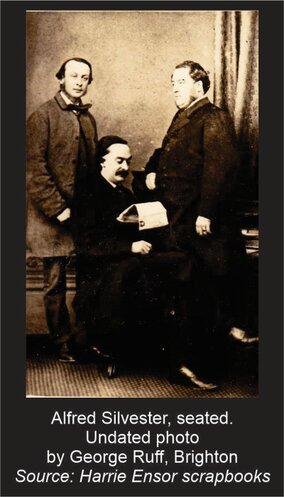

Alfred Silvester – the Fakir of Oolu and his Family of Magic

Chapter Two

“... the aerial suspension act has become common property; it has been utilised in burlesque, while some persons have nearly made a serious drama of it. Many performers have done the trick as a dry, hard, fact; the only man who has got a spark of beauty and poetry out of it is the Fakir of Oolu.” - London and Provincial Entr'acte, July 4, 1874

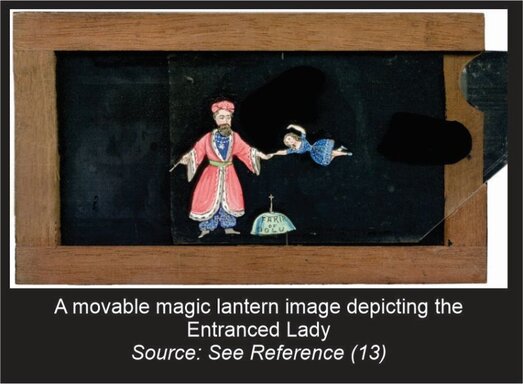

The Entranced Lady

As Alfred Silvester returns to Britain in 1872, we examine the illusion which, more than any other of his feats, made him famous. The Entranced Lady was handed down and performed by all the later generations of Silvesters.

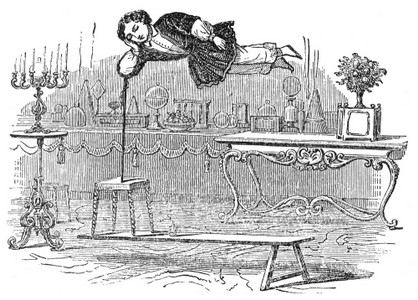

The “Aerial Suspension” was nothing like a new trick. The apparent magical suspension of a person leaning on a single pole, or seated in the air, can be traced back to the beginning of the 1800s, but the illusion we know today was created in 1847 by legendary French magician, Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin (1805-1871) as “La Suspension Ethéréene”. His son, Eugene, stepped up on a platform, itself seemingly without any support at one end, and stood on a stool with his arms resting on two upright poles. Under the supposed influence of a whiff of the new wonder-chemical, Ether, he became drowsy, and Robert-Houdin drew away one of the supports, leaving his son hanging in the air, his only connection to the ground being the single pole under one arm. From this position, his father then lifted Eugene’s feet in the air to a horizontal position, where he remained, delicately suspended on the flimsy support.

It was a fabulous feat, and one which brought Robert-Houdin to the pinnacle of honour in the magic world. Even today, the illusion is performed using much the same methods as the original (a relatively uncomplicated piece of mechanism, which might be found by a simple internet search) and is often referred to as the ‘Broomstick Illusion’, notable performers in Australia being Timothy Hyde and The Amazing Lynda, and illusionist Cosentino. In a modern context the illusion is performed with pace, the assistant being raised from a suspended upright position, to a 45 degree angle, and then to the horizontal, before being returned to earth.

By the time Alfred Silvester discovered the trick in 1869 New York, it had become entirely commonplace, seen in the repertoires of the biggest names across the world, and many small-time magicians. The suspension was a ‘standard’; it had already been presented in Australia, brought here first by the Wizard Joseph Jacobs in 1855, followed by Professor James Eagle (1861), William Montague Murray (1862) and Professor Hennicke (1866).

Yet Silvester re-vitalised the Aerial Suspension, not only with some new mechanical improvements, but by applying his theatrical artistry to a new form of stage presentation. This happened as an evolutionary process, but certainly by the time of his return to Britain, Alfred had been performing the Suspension for a couple of years, and his basic presentation was well established.

Curiously, most magical histories note only that Silvester was responsible for being able to remove the final supporting rod, leaving his assistant floating in mid-air. As will be seen, his illusion featured a number of other significant advances over the Robert-Houdin original, which we will examine before moving on to Silvester’s 1872 performances in Britain.

The Magnetic Wand – As a preface to the main illusion, Silvester took a common magic wand and, by the methods mentioned in Chapter One, showed that it would magically cling, suspended, to his fingertips in various positions.

Lighting and Costuming –

Robert Kudarz, M-U-M magazine March 1920: “The piece de resistance of Dr. Silvester's entertainment was of course his "Beautiful Entranced Lady." Nothing more spirituelle or amazing than this suspension could easily be imagined. The whole performance of Miss Daisy Silvester was a series of beautiful figures in all kinds of graceful and elegant attitudes, from the winged figure of Mercury, ‘alighting as it were upon a heaven-kissing hill,’ to the entranced young lady recumbent upon nothing - the "last link severed."

Robert Kudarz, M-U-M magazine March 1920: “The piece de resistance of Dr. Silvester's entertainment was of course his "Beautiful Entranced Lady." Nothing more spirituelle or amazing than this suspension could easily be imagined. The whole performance of Miss Daisy Silvester was a series of beautiful figures in all kinds of graceful and elegant attitudes, from the winged figure of Mercury, ‘alighting as it were upon a heaven-kissing hill,’ to the entranced young lady recumbent upon nothing - the "last link severed."

It was in the purposes to which Dr. Silvester turned the “mesmeric deep” that the really extraordinary merit of this performance was to be found. By the aid of drapery he made the sleeper assume classical and mythological forms, national and symbolic personifications, and scriptural and poetic figures of great beauty. There was also a most in genius mode of heightening the effect. Coloured rays of the most delicate tints were thrown on the figures, until the sleeping form became almost brilliant with variegated light.

In the representation of angelic forms, where the effect in the first instance was sculpturesque, the chromatic effects were of exquisite delicacy and there could be no question whatever of the interest which this exhibition excited, managed as it was with such perfect ease and wonderful skill.”

It seems rather astonishing, from a modern viewpoint, that the Entranced Lady (who was Alfred’s younger daughter, Daisy, pressed into service following the tragic passing of Polly Silvester in the U.S.) could be left suspended in the air for perhaps fifteen minutes, while she was adorned in various draperies. Not only would a contemporary audience not sit still for such a presentation, the very mechanics of the device must have been extremely uncomfortable to bear for the assistant, even when hanging in the first, upright, position. However, not only did audiences of 1872 enjoy the performance, it was praised as something of the most artistic nature. “The picture being well deserving of the applause it elicits”, said the press of his performance at Cremorne Gardens, “The picture she presented when arranged in the attitude of prayer was exceedingly pretty, and this part of the entertainment is sufficiently meritorious to attain popularity without the aid of 'bunkum' ...."

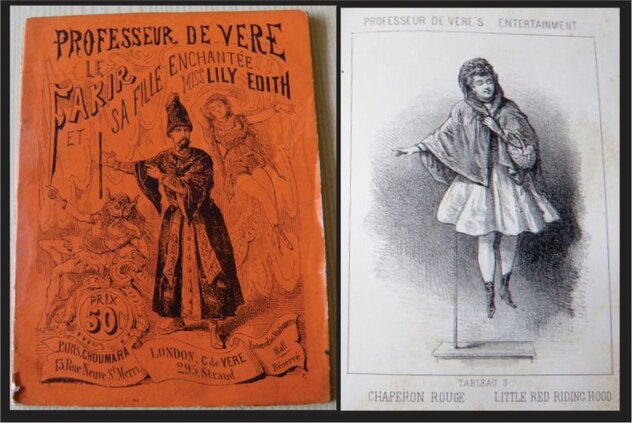

This presentation was also adopted, around 1873, by Charles De Vere (Herbert Williams 1843-1931). De Vere was a professional acquaintance of Silvester’s, so his similar performance, on the Continent, was of no issue to Alfred, and is likely to have been have been by mutual agreement. De Vere, whose wife performed as “Okita” and his daughter as “Ionia, the Goddess of Mystery” [see her amazing tale at note (2) ] issued a scarce little booklet, “Professeur De Vere Le Fakir et Sa Fille Enchantée Miss Lily Edith”, consisting of a series of illustrations showing his assistant in some of the artistic poses adopted.

Self-Rising and Revolving Lady –

Quite when he introduced these two features is unclear, but they are mentioned in press reviews of 1873/1874. This description is from Adelaide, Australia. The Evening Journal of December 12, 1876 reviewed the illusion presently being called the “Aerialist’s Dream”:-

“The Fakir of Oolu, in his gorgeous eastern dress, introduced the Aerialist’s Dream, which appeared to be a very comfortable one, judging from the graceful and easy postures the ‘entranced lady’ was thrown into at his bidding. The bills informed the audience that the Fakir would cause the young lady, by the use of a fan, to rise into a horizontal position and at his will to follow him, making a complete circle of the stage, which she proceeded to do, revolving slowly round the slender upright upon which her elbow rested. Dr. Peel, at the request of the audience, went upon the stage, and having walked round the lady stated he could see no suspending wires, which announcement was received with applause.

“The Fakir of Oolu, in his gorgeous eastern dress, introduced the Aerialist’s Dream, which appeared to be a very comfortable one, judging from the graceful and easy postures the ‘entranced lady’ was thrown into at his bidding. The bills informed the audience that the Fakir would cause the young lady, by the use of a fan, to rise into a horizontal position and at his will to follow him, making a complete circle of the stage, which she proceeded to do, revolving slowly round the slender upright upon which her elbow rested. Dr. Peel, at the request of the audience, went upon the stage, and having walked round the lady stated he could see no suspending wires, which announcement was received with applause.

In 1884 (February 5), the Argus reviewed the performance at the Melbourne Opera House. We will pass over the ostentatious use of not one, but two, floating ladies, and quote the review:

“The second part consisted of Dr. Silvester’s special feat, and that by which he is best known, namely the suspension in mid-air of two ladies. His assistants … became alternately angels, goddesses of liberty, warrior and Mercuries, and one of them was ‘wafted’ by the Fakir from a perpendicular to a horizontal position, amidst the loud applause of the audience.”

The two enhancements mentioned here are not seen in modern-day performances, and the secret mechanisms which made them happen seem to be undocumented and possibly unknown. For the assistant to revolve around the axis of the supporting pole would only require a suitable pivot plate in the base and (despite the above review) probably a wire connecting the magician to the lady’s legs. However we have no documents to back up this view. Likewise, mechanics of the self-rising feature might be suspected, but there does not appear to be any readily available confirmation as to how this worked.

A short paragraph by Professor Hoffmann in “Modern Magic” (1876) seems to be overlooked:

“… [the Aerial Suspension] was revived in a new form by the Fakir of Oolu (Professor Sylvester) in England, and contemporaneously by De Vere on the Continent … few have presented it with the same completeness as the two performers named … Recent mechanical improvements, to which the last-named Professor has materially contributed, have greatly heightened the effect of the trick – the lady being made to rise spontaneously from the perpendicular to the horizontal position, and to continue to float in the air after her last ostensible support has been removed. Apart from these special mysteries, which we are not at liberty to reveal, the trick is as follows…”

Hoffmann’s wording indicates a collaboration between Silvester and De Vere, which would account for their shared use of the same presentation.

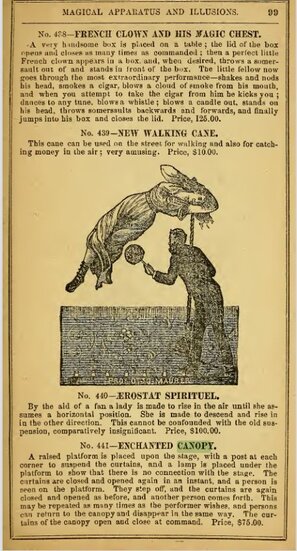

The 1884 catalogue of Otto Maurer (1846-1900), a New York manufacturer of magic apparatus, advertises the “Aerostat Sprituel – by the aid of a fan a lady is made to rise in the air until she assumes a horizontal position. She is made to descend and rise in the other direction.” Directly below this item is the secret, for sale, of the Enchanted Canopy.

The Marvel of Mecca – in 1867, Alfred Stoddart, the brother of the original presenter of “The Sphinx” illusion (3) was presenting an illusion he called The Marvel of Mecca. In 1869 he took out a patent (British Patent 689, March 7, 1869) for the premise of his feat, which was based on the same illusionary principle as The Sphinx; namely, two angled surfaces which reflected the nearby curtains and concealed what was behind.

The Mecca illusion seems to have been performed in a fashion similar to the Aerial Suspension. “A young lady appears on the stage, and places herself in a recumbent position upon a couch, resting her right elbow upon a common walking stick. The couch is withdrawn from beneath her, and the stick is also removed and she appears, without visible support, reclining in empty space.”

In this case, the supporting rod was seemingly removed, but the true support was hidden by two lengths of polished metal, set at an angle to reflect the backdrop. Stodare’s patent suggested other possible uses of the mirrored pole.

The Marvel of Mecca, though seen in use by other illusionists up to about 1882, does not appear to have become a great success. It would have been a more static presentation, lacking in the visual flash of the original Aerial Suspension.

However, during his tour of the United States, Alfred Silvester advertised a Great Aerial Suspension under that same title, “The Marvel of Mecca”. As early as June 1870 (4) until at least March 1872, he used this name, though it is unclear whether he followed Stodare’s presentation, or (we might suspect) that he was experimenting with Stodare’s mirrored pole in conjunction with the Robert-Houdin suspension. Newspaper reviews are unhelpful, the first notice in the New York Clipper saying that “the Professor and Miss Schott present what is called on the bill ‘The Great Aerial Suspension, the Marvel of Mecca,’ which is the old feat of suspending a person in mid-air by means of invisible agencies … this feat has often been performed here but never with better success.”

All things considered, we would like to think that Silvester, who was plainly an aficionado of the angled-mirror principle, was experimenting with raising his Entranced Lady into the air, and then removing the final supporting pole. He may have been unsatisfied with the results, or the difficulties of dealing with the reflective angles, because ultimately the Marvel of Mecca was mentioned no more. Instead, Alfred Silvester found a more suitable method, and developed his most famous trademark:

The Last Link Severed

Alfred discovered the solution to being able to remove the final supporting pole. At Canterbury Hall, December 14 1872, the South London Chronicle reported him “… for the first time, exhibiting his entranced girl ‘literally standing on nothing, the elbow support being removed.”

As with the other mechanical improvements to his illusion, the “last link” is not definitively explained – most magical histories simply accept the word of others such as Sidney Wrangel Clarke, who wrote (5) “the removal of the second pole was more apparent than real, only a silvered shell being taken away, and the black core, invisible against the dark background, still remained to support the lady. Anyway, Silvestor’s [sic] entertainment obtained a considerable success and was at once copied by other performers.” There is no reason, however, to suppose that this “black art” technique is not the solution to the mystery. Given the available stage lighting at the time (6) (gas, or at best, an oxyhydrogen lamp) the black pole would have disappeared into the background easily; the only slight difficulty being Kudarz’ reference to coloured lights being thrown on the subject. In April 1873 the Bradford Observer said, “… this concluding act would have been more satisfactory if there had been a little more light upon the subject – indeed, the light throughout is kept rather lower than we have seen in previous performances.”

So, Alfred Silvester’s enhancements to the Aerial Suspension are considerably greater than usually acknowledged.

His final contribution, however, was not mechanical, but theatrical.

His final contribution, however, was not mechanical, but theatrical.

Alfred Silvester became the Fakir of Oolu.

The Fakir of Oolu in Britain

‘The Era’ of July 21, 1872, announced the availability of “The Fakir of Oolu, whose success has been unparalleled in America, having just arrived in the steamship California.” On July 29, the Fakir made his ‘first’ appearance at the Cremorne Pleasure Gardens in Chelsea, presenting the Aerial Suspension on a varied bill of performers.

The Morning Advertiser (7) had some fun with the new fellow on the block:

"Our knowledge of Oolu is not profound. We have not an Ooluer in our circle; have not recollection of any Oolu ambassador having taken up his abode at Claridge's, of any Oolu tenor having appeared on the operatic stage, or of any Ooluist having in any form, missionary or otherwise, previously distinguished itself in reference to this country ... When, therefore, we perceived the announcement that the Fakir of Oolu was at Cremorne Gardens, our determination was soon taken; we resolved at once to seek out the Fakir and to behold him fake. The latter may not be the precise term to apply to his performances but ... we are right in affirming of the Fakir that he did his faking deftly ... he is a conjuror, and a very clever expert in that art ... the great feature is a mesmeric trick, in which a lady is sustained in the air, in a manner which would render her liable under the Vagrant Act as 'having no visible means of support' ... this is most ingenious, and uncommonly well managed .. That the Ooluers are in the habit of throwing their wives into a comatose state and then leaving them to sleep placidly reposing on the points of spears is a circumstance of a truly gratifying character."

"Our knowledge of Oolu is not profound. We have not an Ooluer in our circle; have not recollection of any Oolu ambassador having taken up his abode at Claridge's, of any Oolu tenor having appeared on the operatic stage, or of any Ooluist having in any form, missionary or otherwise, previously distinguished itself in reference to this country ... When, therefore, we perceived the announcement that the Fakir of Oolu was at Cremorne Gardens, our determination was soon taken; we resolved at once to seek out the Fakir and to behold him fake. The latter may not be the precise term to apply to his performances but ... we are right in affirming of the Fakir that he did his faking deftly ... he is a conjuror, and a very clever expert in that art ... the great feature is a mesmeric trick, in which a lady is sustained in the air, in a manner which would render her liable under the Vagrant Act as 'having no visible means of support' ... this is most ingenious, and uncommonly well managed .. That the Ooluers are in the habit of throwing their wives into a comatose state and then leaving them to sleep placidly reposing on the points of spears is a circumstance of a truly gratifying character."

Silvester’s identity was certainly no secret, as the ‘Globe’ named him immediately. Aside from the public’s difficulty in deciding how to pronounce the word “Fakir” ( fuh·keeuh ), there seems little reason to suppose that his adoption of a mystical foreign figure was seen as anything but what it was; a theatrical device to enhance the artistry of the performance. While, today, accusations of cultural appropriation might be levelled, Silvester was not impersonating a nationality in the same way as many other magicians (such as William Robinson / Chung Ling Soo). The “Mohammedan” connections, with the exception of a period in 1873, were only mentioned in passing in the early days, and as will be seen, the Fakir spoke to his audience with no pretend accent or affectation. He was dressed in beautiful robes, now sporting an imposing full-faced beard, and he was considerably stouter than the photographs of the early 1860s show him. In short, the Fakir was a splash of theatrical colour.

‘The Era’ of August 4, 1872, though not very complimentary about the Fakir, gives a good impression of Alfred’s early performances. In later years there is no particular indication that he wore his Fakir robes throughout the entire show; he may well have saved those for his Suspension trick; but at Cremorne he was in costume for the entire act.

“And who is the Fakir of Oolu? A fakir is, we believe, a Mohammedan Monk or a dancing dervish, or something after their kind. The Fakir of Cremorne, for Cremorne, we suppose is synonymous in this case with Oolu, is nothing of the sort. He hails, we understand, from America, and it is, we presume, due to Mr. Barnum’s advice that he comes before us with so astounding and awe-inspiring a title. From a fakir we certainly expected something novel, and as certainly we were disappointed. His performance occupies about half an hour, and is as old as the hills. The Fakir is neither more nor less than a conjuror, and differs only from other professors of the art by claiming to perform in reality those feats which they are content to seem to perform.

On the evening of our visit “the Fakir” commenced his entertainment by producing a flower in his button-hole at a touch from his wand, and by extracting at least a hundred yards of ribbon from a hat borrowed from the audience. From the same hat he subsequently produced a cannon-ball and a bouquet. During the performance of the ribbon trick we should mention that he sang a “Dreaming song” made popular by a well-known comic singer, and concerning this we can only say that he “dreamed” very much out of tune.

The principal feature of the entertainment was, however, to follow, and it is this which the Fakir has come all the way from America to show to the English public as a novelty. This is the old trick in which a lady is apparently made to sleep in the air with nothing for support but a rod upon which her right elbow rests. Many of our readers will not require to be told that this trick was a familiar one twenty and five-and-twenty years ago. But in the Fakir’s performance of it there is a novelty, and it is this:- He assures the audience that no mechanical appliances are brought to bear and that to him is given the power to defy the laws of gravitation. This he does, not in jest, but in earnest, and we doubt not that many who see him and hear him will accept his assurance as the fact. For our part, to put it mildly, we will only say that he ‘postpones’ the truth for the convenience of the moment.

Apart from this, we are disposed to give Mr. Fakir a good deal of credit for the neatness and taste with which the trick is performed. The young lady is posed in the most graceful positions, and is made, by the aid of appropriate costume, to impersonate various characters. Thus we see her as a flower girl, a warrior, a minstrel, a dancer, &c. each posture being well deserving of the applause it elicits. The picture she presented when arranged in the attitude of prayers was exceedingly pretty and this part of the entertainment is sufficiently meritorious to attain popularity without the aid of “bunkum”, and we may remind his Eminence the Fakir that he will not discover the path to public favour by insulting the intelligence of his audience.”

And with a little flurry of co-operative controversy, the Fakir received the publicity he desired and the correspondence served its purpose!

We will not follow every venue or performance of the Fakir who, in the not-uncommon style of the time, was able to jump between two or sometimes three separate venues in a single evening. After finishing at the Cremorne Gardens at the end of August, he was also seen at the Surrey Gardens, at the Royal Cambridge music hall, Bishopsgate (November), but chiefly at The Oxford music hall where he had an almost continuous run. In November the Oxford suffered another catastrophic fire, and the entire Oxford troupe moved to Canterbury Hall. He was described by the Morning Advertiser (9) with his “Beautiful Entranced Girl” as “a stalwart gentleman in ordinary evening dress, with a perfect command of the English language and with not a vestige of anything Oriental about him .”

By November, Silvester had added the Talking Lion to his performances, no doubt allowing him to present different acts at each of the theatres; by late November he was noted playing at the Canterbury, Cambridge and Sun Music Halls where the London and Provincial Entr’acte described him as ‘the leading attraction’. “His suspension performance is most artistically as well as marvellously carried out, and brings heaps of honours to the great magician nightly … We have seen much excellent legerdemain, but none superior to the Fakir’s novel performance with his magic rod.”

“Since his visit to England, there has been many base imitators prowling around trying to copy his style, and also secure engagements on his reputation”, advertised Alfred’s business manager, Arnold Jones. “Managers, however, are not all devoid of common sense, and prefer the genuine performance to trash.” The Fakir’s success was such that he was even the subject of parody acts by other music hall performers, including Leggett and Allen with “The Fakir to Do You” in which they performed the illusion, but with a comedic presentation.

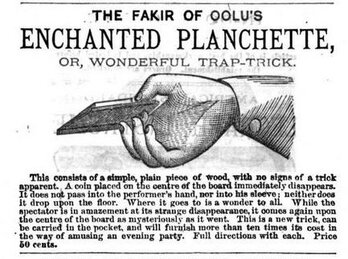

The Enchanted Planchette – Further indicating a business relationship between Charles De Vere and Silvester, the Magical Repository at 295 Strand, operated by De Vere, started advertising ‘The Enchanted Flower’ (the buttonhole trick, ‘as performed by the Fakir of Oolu’ ) and ‘The Fakir of Oolu’s Enchanted Planchette’ with sole manufacturing and sale rights. While it cannot be confirmed that Silvester invented this trick, a coin vanishing from a small wooden board, the trick itself looks similar to one still being sold today.

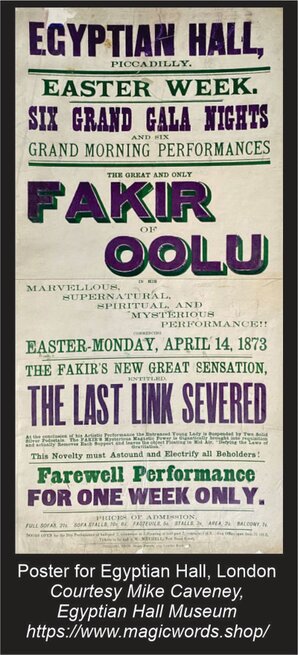

On Boxing Night, 1872, Silvester introduced the illusion feature with which his name is still linked. Advertising for Canterbury Hall warned “Consternation! The Last Link Severed. The Fakir of Oolu’s Beauty Floats Alone – a Denizen of the Air. The Host of Imitators Foiled and Scattered. This Great Man only to be seen at The Canterbury Hall.” Or “The Fakir of Oolu will sever the last support and leave his Beautiful Entranced Girl to Tread the Air!! The host of wretched imitators at every Hall and Theatre confounded!”

The Entranced Lady was only performed at the Canterbury, where doubtless the correct staging could be achieved.

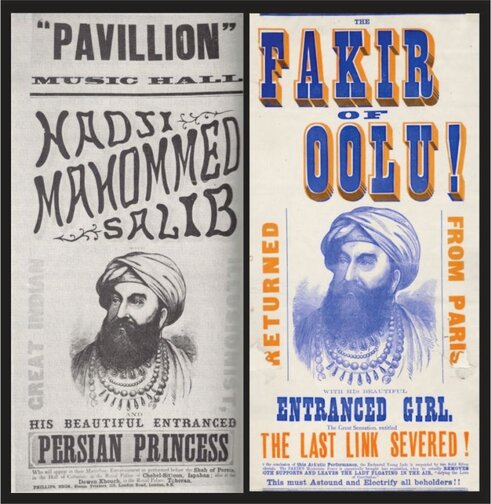

1873 - The Mystery of Hadji Mahommed Salib

Curiously, considering it is today the Fakir’s main claim to fame, there does not seem to have been an enormous response to this new novelty. It was certainly a useful publicity coup for Silvester, but he was already doing so well with his act that his success rested on the artistic nature of the Suspension. “The Entranced Girl under his hand”, wrote the London Evening Standard on December 28, “changes character and position with wonderful facility and represents Britannia, Columbia, Erin, Scotia and the Goddess of Liberty. In addition to this the Fakir illustrates an extraordinary phase in the laws of gravitation by lifting the entranced girl from the stage, and making her apparently to float in the air without the aid of material or mechanical support of any kind.”

Coming into 1873, Alfred was dealing with a number of impositions upon his act, one of whom was a Professor Beaumont up north in Manchester, “who will appear in his great entertainment of the Fakir of Oolus.” Another burlesque act, the Fakir to Suit You” was performed by Alf George and Nelly Griffiths at the Marylebone Music Hall and, at Berner’s Hall in London, Madame Gilliland Card was advertising “Mystery Exposed – will cause her Enchanted Girl to Float in the Air without the aid of mesmerism, gravitation &c.” Alfred seems to have taken Professor Beaumont seriously enough to travel up to Manchester in January and perform at the Alexandra-Hall there for a week, in order to kill off the competition. On his return to Canterbury Hall he advertised as “The Fakir of Oolu (The original, no wretched imitator)”.

Some plan was in mind, as he began to advertise ‘last weeks in London’ at the end of January, and then took up an extended engagement with Mr. Hamilton’s acclaimed dioramic presentation at the Agricultural Hall, illustrating the overland route to Calcutta. For this purpose the Suspension became his ‘beautiful Indian illusion’.

From March, while performing at various venues, Silvester said that his engagements were limited, prior to his return to the United States. But before this, he would advertise (10) “It has been brought to my notice that a number of would-be ‘Fakirs’ have been going about the country performing and using my title, dialogue, music and copying my entertainment in general. I have hitherto refrained from instituting legal proceedings against such persons; but I now hereby give notice that my entertainment, characters, title and posters, are duly registered according to law. And that I shall hereafter take proceedings as I may be advised…”The Fakir and his Lady’s last appearance in London, for now, was a week’s season at the famous home of magic, Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly, from April 14. “Being, as it seemed, upon nothing, she appeared to be almost floating in the air, and so well is the illusion kept up that many people expected her to fall every instant, and some old ladies were quite demonstrative in their expressions of sympathy and alarm.” The London Evening Standard reported that “finally, one of the poles is waved over her head, under her feet, and on all sides of her, the object being to negative the notion that she is sustained in her position by other means than the magnetism of the exhibitor. The Fakir says he is not a spiritualist, but an artist.”

Silvester headed northwards in late April and moved between Bradford and Liverpool where he was at the New Star Music Hall well into May. Liverpool would seem to have been a jump-off point for any trip back to the United States; but no such trip happened, and on May 29 the Fakir was reported to be at the Southminster Theatre in Edinburgh.

Yet another band-wagon jumper had appeared in early March. The Gonza’s Grand Transatlantic Combination Company was seen until June, with a Professor Willene Essman who styled himself the Fakeer of Delhi, and promoted the extraordinary scene of “The Enchanted Lady and Gnome Floating Through the Air”!

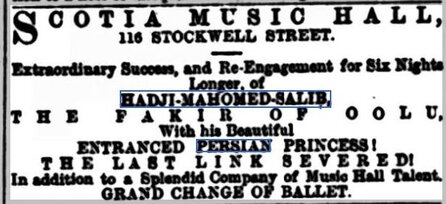

With such an assortment of hangers-on, it now seemed that one more copyist was trying to stake his claim. The Entranced Lady, as performed by one “Hadji Mahommed Salib” began to make an appearance around June. Despite the obvious suspicion that this new mystic was just another boy from Brixton, careful searching and examination of the facts reveals that Alfred Silvester had, indeed, adopted the title.

From June 2, at the Scotia Music Hall in Glasgow, Silvester performed, with only the usual advertisements proclaiming the Only and Original Fakir of Oolu and his Entranced Girl. By June 18, still at the Scotia, Silvester added a name and became “Hadji-Mahomed-Salib, the Fakir of Oolu”. The name varied during its short life, being sometimes ‘Mahomed’ or “Mahommed”, and “Salib / Sahib / Salid” at various times. The Entranced Lady now became The Entranced Persian Princess.

Confusing the issue, the London press advertised the “Original Fakir of Oolu … will shortly visit London”, but in his next appearance, at the London Pavilion on June 23 the magician was named only as Hadji Mahommed Sahib, the Great Indian Illusionist, and Naomi the entranced Persian Princess. Silvester had apparently rushed this new character name, as one variant of his Hadji Mahommed poster reads “Pavillion” instead of “Pavilion”, and “Entrances” instead of “Entranced”. However the image on the poster for Salib was unquestionably Alfred Silvester.

He was seen at the Royal Surrey Gardens, and the Cremorne Gardens, into mid-July. Then the Fakir/Sahib vanished from Britain, and it is only by working backwards that we discover that Alfred had gone to France.

Promoted solely as Hadji Mahommed Sahid, he worked at the Cirque des Champs-Élysées, Paris, from around July 28 to around August 16. An insight to his performing style, as well as a little gratuitous exposure, comes from La Press Ilustre, August 9:

Mohammed-Sahid - indien de Oolu

“The Cirque des Champs-Élysées calls to itself everything that is curious. It is like the charmers of India. There's one at the Cirque who, by magnetic power manages to suspend in the air a young blonde girl of seventeen years old, and make her assume mythological and warlike poses.

Is it really by magnetic power? The trick consists, says M. Paul de Saint-Victor, in suspending the body by way of a stick stuck in the ground, by means of a spring passed to its arm. The spring corresponds to an armature hidden under the clothes, which allows the girl to glide in the air, at the end of this pole, without too much fatigue. However Mohammed-Sahid, a fat man in a dress of muslin, round like a full moon, under his ‘date-merchant’ turban, projects on the girl magnetic passes to make her sleep while standing. The ‘fluid’ operates or pretends to operate; then the sleeper changes into a sculpted being. Mohammed-Sahid goes around and dislocates in all directions his poser, who bends, like an articulated mannequin, to his manipulations. He joins her hands and attaches to her shoulders small wings in gilded paper, and it is an angel lying towards the sky. Then, as a reward for the docility that she brings to his exercises, he sticks to her back two big fluffy wings; and from the simple ungraded angel she was she becomes an archangel. His only task remaining is to change her into a god: a caduceus (Emblem of Hermes, which became the mark of messengers) put in her hand, a petase (headdress with wings) with feather, winged heel pads on her feet complete the scene. It is the Mercury of John of Bologna in celestial tour and splitting the clouds.

What is amusing in this prolonged suspension is the abracadabra pantomime of the operator. At each of the living tableaux that he creates with his model, he swoons, he falls in ecstasy, he affirms by a well-felt gesticulation that art cannot go beyond. This enchanter is especially full of himself, and believes deeply that "it has happened." It is very amusing and very interesting; but when will the great jugglers of India be brought to us, the marvellous miracle workers?”

Of interest is that Silvester’s act was not the first to appear in France. In April 1873, magician and magic dealer, Charles De Vere, had moved to France, where he performed the Suspension for three months with his floating lady, Julia Ferrett, at the Théâtre de la Gaîté in the Montparnasse quarter of Paris. (2)

By September 16, Alfred Silvester had returned to The Oxford in London, advertising “The Fakir of Oolu returned from Paris in his natural garb.” Hadji Mahommed Sahib was seen no more, and the only remaining question is – why the change?

The answer lies in world affairs, and the public’s love of pomp and ceremony. In 1873, Naser al-Din Shah, the fourth Shah of Persia from 1846-1896, was making a tour of Europe. He arrived in England at the end of June, and in early July was at Paris. The exoticism and ‘mystery’ of Persia was suddenly on everyone’s lips, and in the best Barnumesque fashion, Alfred had decided to cash in on the craze.

Although we say that Hadji Mahommed was seen no more, there is one exception. Six years later, in Melbourne Australia, (7) “The Age” reported, “The Silvester and [Nellie] Vivian entertainment attracted a good house to the Fitzroy Town Hall on Saturday evening. Hadji Mahommed Sahib, an illusionist, made his first appearance, and created a favourable impression.” On this occasion, the performer was not the original Alfred Silvester – it was his son, Alfred2 !

Provincial Tours and Repertoire 1873-1874

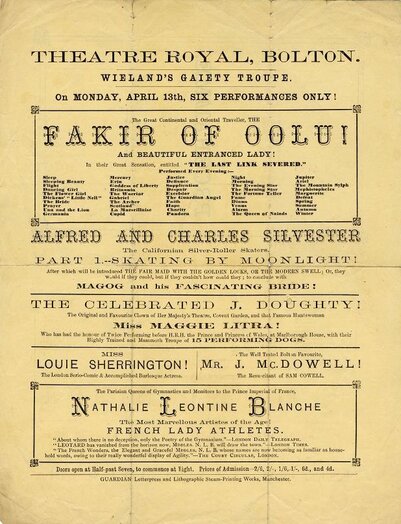

Provincial Tours and Repertoire 1873-1874Upon his return to London, Alfred was back at The Oxford for the most part, where, said the press his show “is still relished”. However, having been in London for so long, and possibly reaching the extent of the Entranced Lady’s drawing power, he now started to look further afield. A southern tour covered Brighton (performing with magician Herr Tolmaque (12) at the Grand Concert Hall), Plymouth’s Albert Hall for an extended season, then on to Bolton, and in 1874 south-west into Exeter, Torquay, Penzance and Truro. In July he returned to the Oxford, and then went North-East to Norwich in August (Victoria Hall), East Lynn in September, and finally in October, the Royal Victoria Rooms at Southampton. His fame was now such that a racehorse was named The Fakir of Oolu and seems to have competed successfully on a regular basis.

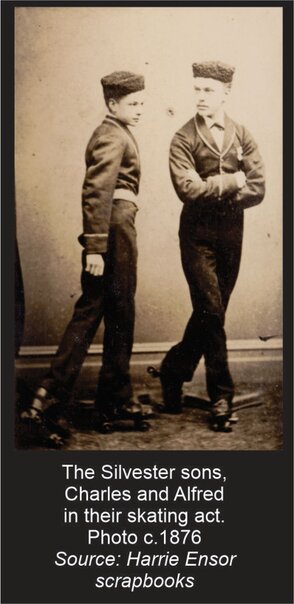

The show, now billed as “Mysteria” continued to expand, with the usual repertoire of the Suspension, and Leo the Talking Lion, being supplemented with an opening series of small standard magic, and the start of some anti-spiritualistic effects such as Blood Writing on the Arm and the Sealed Packet mystery. Completing the family involvement, Alfred’s two sons, Charles and Alfred2 were introduced as the Californian Silver Roller Skaters.

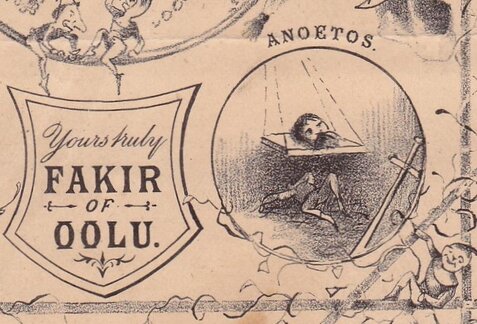

In line with his love of theatrical plots and miniature dramas (not to mention his fondness for a disembodied head illusion), Silvester created a whole staging around the illusion of a head sitting on a tray suspended by ropes. He called it “Anoetos”, a Greek term meaning “foolish,” “senseless,” “uncomprehending,” or “unreasonable” – but in Silvester’s usage, “Incomprehensible”.

This description is from 1875 in Australia:

Anoetos, a legend of the Hartz Mountains.

"Some centuries ago a Grand Duke lived in Germany whose tyrannical bearing rendered him hateful to his subjects, and a conspiracy against his life was entered into. The plot was discovered, and one of the leading conspirators arrested, but he resolutely refused to disclose the names of those who had joined with him, and he was beheaded without the secret becoming known. It came, however, to the knowledge of the duke that an alchemist of renown, residing in his dominions, had boasted that he could, by the power of his magic spells, cause the dead man to reveal the secret, and he charged him, on pain of banishment and confiscation of his property if he failed, instantly to put his boasted powers to the test.

Anoetos, a legend of the Hartz Mountains.

"Some centuries ago a Grand Duke lived in Germany whose tyrannical bearing rendered him hateful to his subjects, and a conspiracy against his life was entered into. The plot was discovered, and one of the leading conspirators arrested, but he resolutely refused to disclose the names of those who had joined with him, and he was beheaded without the secret becoming known. It came, however, to the knowledge of the duke that an alchemist of renown, residing in his dominions, had boasted that he could, by the power of his magic spells, cause the dead man to reveal the secret, and he charged him, on pain of banishment and confiscation of his property if he failed, instantly to put his boasted powers to the test.

Here it is that the scene opens. The execution is just over, and the corpse of the conspirator is seen on the ground amidst the straw, whilst above the head, dissevered from the body, lies on a tray which sways gently to and fro. On the one side stands the masked executioner, leaning on his two-edged sword; and on the other, the alchemist about to exercise his magic force. The power of the alchemist is soon made apparent, the head shows signs of life, and turns uneasily, the eyes open, and the lips move, whilst the body is disturbed by convulsive twitchings. Commanded to disclose the secret, the dead man obeys, and a deep sepulchral voice issues from the mouth of the dissevered head. Having fulfilled his promise, the alchemist permits the victim to return to death; and as the head falls back lifeless, angels are seen bending in pity over the fallen corpse. The illusion is very cleverly managed, and by the skilful use of limelight the head is made to exhibit a very ghastly appearance.... the performance is clever, but is not so pleasing in character as the others with which the Fakir deludes the senses of visitors."

The Entr’acte of July 25, 1874 published an effusive tribute to the Fakir of Oolu, and while it might read as something of a publicist’s dream, it clearly was borne out by the Fakir’s success in Britain:

POPULAR ENTERTAINERS. No. VIII-THE FAKIR OF OOLU. “The hero of Aerial Suspension, the high-priest of mystification, the Fakir of Oolu, has taken prominent rank among modern magicians. Your ordinary illusionist is but a sorry entertainer - a bungling reproducer of antiquated tricks, devoid of dexterity, and deficient in manipulative skill. The mechanism of his art obtrudes itself on the perception of his audience, and the more delicate touches of skill are never discernible in his performance. From the very force of this painful experience of the average illusionist, one is impelled to a recognition of the sterling merits of an entertainment such as that in which the Fakir of Oolu has been for some years appearing. The test of time is admittedly a severe and reliable one to apply to any public performer’s qualifications; if this be so, the complete success of the Fakir of Oolu’s entertainment is sufficiently established - since it has for so long a time enjoyed an unbroken lease of popularity.

Not many months since the “Times” described the Fakir as a man few words and marvellous deeds; the description is peculiarly apt. In his performance we are afflicted with none of that imbecile chatter and vexatious verbosity which are so frequently employed by inefficient conjurors to cloak their clumsiness. His Aerial Suspension illusion is unapproached by any other entertainment of a similar nature with which we are conversant. The thoroughly artistic grace of the various attitudes assumed by the “beautiful entranced girl” under his manipulations is, in itself, sufficient to stamp the performance as one immeasurably in advance of the ordinary entertainment. Into the business nothing vulgar or flashy is ever allowed to creep; in short his exhibition is one which appeals rather to the educated appreciation of the respectable amusement-seeker than the rowdy taste of the ubiquitous hall ’Arry.

Since his recent return to the metropolis we note many important and elaborate additions to the Fakir’s programme. Now the mystified spectator may behold not only the wonders of Blood Writing, and the fathomless deciphering of the Sealed Packet, but in his aerial suspension illusion the Fakir fans the “aerially suspended” young lady from one position to another, and, finally, causes her while recumbent in the air to follow him round the stage. This, on paper, almost surpasses belief, yet this, and much more, is accomplished by the expert practitioner. It is, we are aware, no easy thing for an illusionist to strike out a new path for himself in his profession; and it is by reason of the strict novelty of all that the subject this notice introduces to the public that we unhesitatingly pronounce him the head of that branch of the entertaining art with which he is identified. Early in his successful career as an Eastern “magician” the Fakir encountered much factitious opposition on the part of the leading theatrical organ. That opposition he has long since lived down; and, in so doing, has no less asserted his own legitimate claim to popularity than demonstrated the puny weight attaching to the “Era’s” spiteful condemnation.

In conclusion, we can only reiterate the opinion often expressed in these columns as to the chaste, elegant and artistic nature of the entertainment submitted by the Fakir of Oolu. Its chief charm in our eyes is the finished skill which is ever apparent during its performance; though to this high qualification for success must certainly be added the strikingly artistic perception which gives life and colour to the charming “pictures” that contribute so materially to the success of the Aerial Suspension illusion.”

In October 1874 there were reports that Alfred Silvester had been engaged to take his show across the world for an appearance in Australia. Although he did not realise it, Australia would become home for Alfred and generations of his descendants.

REFERENCES FOR CHAPTER TWO

(1) ‘Where Houdini Was Wrong’ – Maurice Sardina 1947, translated Victor Farelli 1950. Magic Wand publication.

(2) De Vere’s daughter Clementine had an astonishing life, on stage as “Ionia” and in her many life adventures, during which she married an Old World prince. Her tale, with that of Charles De Vere, and his performing wife “Okita”, has been researched in great detail by Charles Greene III, in “Ionia – Magician Princess – Secrets Unlocked” (2022) - https://www.ioniasecrets.com/

(3) Alfred Stoddart was the brother of the original presenter of The Sphinx, Joseph Stoddart. In 1867 he was performing as Alfred Stodare. The unravelling of the entangled history of “Colonel Stodare” may be found in “Stodare – The Enigma Variations” by Prof. Edwin A. Dawes, Kaufman and Company 1998. A copy of the “Marvel of Mecca” patent is also published here.

(4) New York Clipper, June 18; unclear but possibly reporting the appearance of Silvester and Schott at the National Theatre, Washington D.C. in the pantomime “Jack and the Beanstalk”. The final mention is at the Institute Hall, Wilmington, March 1 1872.

(5) Sidney Wrangel Clarke, “The Annals of Conjuring”, originally published in the Magic Wand magazine 1924 to 1928.

(6) The first theatrical production in the world to be lit by electric light, was Gilbert & Sullivan’s “Patience” in October 1881 at the Savoy Theatre.

(7) Morning Advertiser, August 2, 1872.

(8) See The Era, August 24, 25 1872

(9) Morning Advertiser, September 4, 1872

(10) London and Provincial Ent’acte, April 12, 1873

(11) The Age, Melbourne, February 17, 1879 p.3

(12) Martin Beauforte Tolmaque, by coincidence, would follow Silvester to Australia in 1875, but had very little success. His life ended in Australia, where his mental health progressively declined, and in 1896 he was presented before a court charged with being of unsound mind. In “Magical Nights at the Theatre” Charles Waller reports that Houdini claimed to have found Tolmaque’s grave in the Melbourne General Cemetery, but in fact he was buried in a pauper’s plot at the Cornelian Bay Cemetery in Hobart, Tasmania, 1907.

(13) The image of the “Fakir” magic lantern slide is from “Realms of Light – Uses and Perceptions of the Magic Lantern from the 17th to the 21st Century”, a collection of essays edited by Richard Crangle, Mervyn Heard and Ine van Dooren, published by the Magic Lantern Society 2005.