Berkeley Lennox, the Gentleman Wizard

What sets apart this "Wizard of the South" from so many others is the apparent refinement of his show, and the strong likelihood that he came from a quality British background. Following the initial publication of this story, Michaele Jeavons, of whom the Wizard proves to be her third great-uncle, provided a number of details which confirm our conclusions and fill in some vital missing information, for which we are greatly indebted.

Writings by the standard magic historians of former years, Robert Kudarz, Charles Waller and Will Alma, make some transcription errors by referring to Lennox as 'Lennot' or 'Lennos'. Waller also makes an assumption that Lennox travelled from Australia back to Europe, returning again with newly made apparatus, and we will later examine this possibility.

Family Origins

The process of identifying a magician, when almost no clues are available, is fraught with the possibility that a simple similarity in name might take the researcher down a completely false path. In the case of Berkeley Lennox, a number of clues at either end of his career give us some hope that his identity can be properly traced.

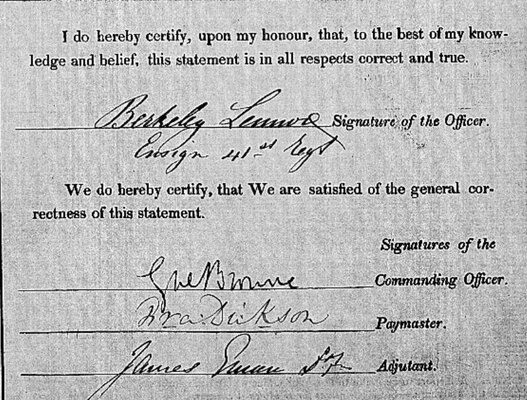

Army records WO 76_238

From his advertising, ‘Professor’ Lennox is known to be Berkeley Lennox. In 1855, court reports name him as Berkeley James Lennox. On multiple occasions (shipping news and court reports), he is also referred to as a “Gentleman” rather than naming a profession, and newspaper reports indicated that he was a performer of some unusual refinement and apparent education, appearing before ‘very respectable’ audiences.

Working backwards from this, military records (1) show a Berkeley James Lennox held the junior commissioned rank of Ensign ‘without purchase’ in the 41st Welsh Regiment of Foot in May 1845, and was reassigned to the 28th Foot on March 31, 1846. The military record, and genealogical records (2) indicate that Berkeley James Lennox was born on July 16 1828 in Saint-Germain Paris. Family research names him as “George Berkeley James Lennox”.

He was the eldest son of Lord Sussex Lennox (1802-1874) (3), and grandson of the 4th Duke of Richmond. Berkeley was baptised at Boxgrove in Sussex on December 27, 1832, four years after his birth. It is notable that his father and mother (Mary Margaret Lawless) married only in April 1828 (4)

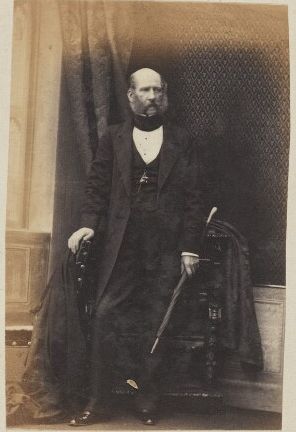

Lord Sussex Lennox

Lord Sussex LennoxThese details also tie in with news reports of the early death, aged just 28, of Berkeley James Lennox in Lima, Peru, while on a return journey home (tying in with both the birth date from his military records, and 1856 departure date from Australia).

By all accounts, his father, Lord Sussex Lennox, was a colourful character. He had, in 1827 faced a financial penalty of £2,500 in an action brought by Baron de Roebeck for ‘criminal conversation with the plaintiff’s wife.’ (5) The Baroness, having eloped with Lord Lennox in Paris, was then divorced by the Baron and married Lennox.

Lord Lennox was also involved in dramatic action in 1842 when, under an assumed name, he sailed to Malta and engaged in a duel with another officer; see The Austral-Asiatic Review February 4, 1842.

In April 1845, the wife of a banker, Mrs. Stone, was also divorced by Mr. Stone on the grounds of adultery with Lord Sussex Lennox. This was around the same time when Berkeley Lennox was enlisted into the regiment.

On these interconnected facts, we believe a strong case has been made for this gentleman magician’s origins. What is not clear is how or why he became a conjurer; but social rank is no guarantee of wealth or even respectability, and an adventurous young man might need to find his own way in the world.

Introduction to Australia

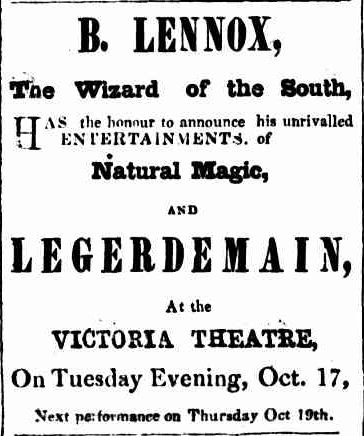

Lennox married Marrianne Blacklin, daughter of George Blacklin, at Athy in County Kildare, Ireland, on March 3, 1853. Shortly afterwards, the ship Mercia departed from Liverpool on May 11, 1853, arriving in Melbourne on August 15 with Mr. Lennox and his wife on board. Lennox was a very young twenty-five year old, yet within days of his arrival he advertised “an extensive cabinet of Mechanical and conjuring apparatus, with which he proposes to give a limited number of performances.” He was, at this stage, announced simply as B. Lennox, though he would soon adopt the hackneyed title “Wizard of the South.” His programme was a well-rounded one, including some sleight of hand, though in the same style of most performers of that era the effects were those of Robert-Houdin and Jacobs.

Melbourne Argus, August 30, 1853 - back page -

Great Attraction at the Terpsichorean Hall, Great Collins-street - Under the distinguished patronage of Colonel Valiant and the Officers of the 40th Regiment on which occasion the Splendid Band of this regiment will be in attendance. Grand entertainment of Natural Magic and Legerdemain, by B. Lennox, on Thursday, the 1st September, 1853. Doors open at half past seven, commence at eight.

Melbourne Argus, September 1, 1853 -

Advertisement - Terpsichorean Hall, Great Collins street, between Russell and Stephen streets. [Stephen Street was renamed Exhibition Street in 1880] Thursday Evening, September 1st, 1853.

Under the distinguished patronage of Colonel Valiant and the Officers of the Fortieth.

B. Lennox, In announcing his performance to the public, begs to state that he has made great improvements in his peculiar profession. He accomplishes, by the combination of physics and mechanics, with his prestidigitation, such extraordinary wonders that, unless seen, they would never be believed. Among the experiments will be introduced –

PART 1 - The Magic Mill, Robin's celebrated Ink Vase Delusion. The Invisible Handkerchief. The Inexhaustible Bottle, which is beyond conception, - any quantity of any spirit being produced from an ordinary quart bottle at the request of the audience.

Clairvoyant Half-crowns, In which Mr. Lennox will unfold the mystery of Second Sight.

PART II - Extraordinary feats of Legerdemain!! in which Mr. L. will prove the fallacy of the axiom that 'Out of nothing nothing comes.’ The Invisible Printer.

A surprise for Ladies; or, a New System of Improvising Flowers, Sweetmeats for Children. The Burnt Pocket Handkerchief.

Freaks of the Merry Jack of Spades - Travelling Cards, The Wonderful Target. The Extraordinary Bottle Delusion. The Flag of Flags; a grand national and personal distribution, but not to be distinguished. The Cornucopia. The Celebrated Cannon Ball Delusion. The Shower of Gold Fish, or Bowls of Neptune. Lennox's Patent Strong Box for the Diggings.

The Performance will be enlivened by the Band of the Fortieth.

Reserved Seats, numbered, 7s. 6d. Stalls, 5s. Promenade, 2s. 6d. Children under 12 years, half price to the reserved seats only.

Reserved seats may be procured at the door of the hall from 12 to 5 on the day of performance. No half price. Doors open at 7 ½ to commence at 8 precisely.

Mr. Lennox begs to inform the public that he intends continuing his performances at the above hall every Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday. Next entertainment on Saturday, September 2nd. Full particulars in advertisements.

Melbourne Argus, Friday September 2, 1853 - page 5 -

A Magician - Last evening Mr. B. Lennox, a recent arrival, introduced in Melbourne another novelty in the shape of some of those magical arts and tricks for which Professor Anderson and others have become celebrated. Several of the tricks were exceedingly well performed and gave great satisfaction to a very respectable audience. For the failure of others, Mr. Lennox apologised on account of imperfections in his machinery. The entertainment is well worthy of a visit by the uninitiated.

Of the show on September 5, the Argus reported that ‘the weather was unfavourable, and the state of the streets such, that very few persons ventured out to the Hall. as the successful performance of some of the experiments depends upon the production by the audience of white handkerchiefs, wedding-rings, &c. which articles were not forthcoming last night, it was found necessary to adjourn the entertainment until Thursday evening, ticket for that evening being given to the persons present. The extraordinary trick of the inexhaustible bottle was, however, performed … and if the performances of this feat may be reckoned as a specimen of the whole entertainment, we think those of our citizens who have not seen the Great Wizard of the North himself, would be highly gratified by a visit to his disciple at the Terpsichorean Hall.’

These performances continued three times weekly at the Terpsichorean Hall, and then Lennox, adopting the “Wizard of the South” by-line, moved to the Temperance Hall at 170 Russell Street, on September 21. The Temperance Hall would, over the years, evolve into the Imperial, Savoy, and Total Theatres, but no longer exists.

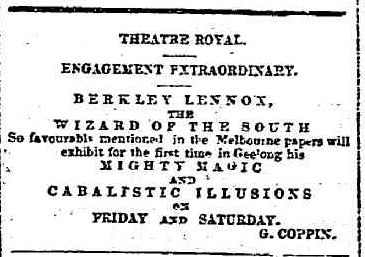

At the end of September, Lennox travelled the 75 kilometres from Melbourne to Geelong, appearing at the Theatre Royal in Malop Street for three nights around September 30 under the auspices of the theatre’s owner, entrepreneur George Coppin.

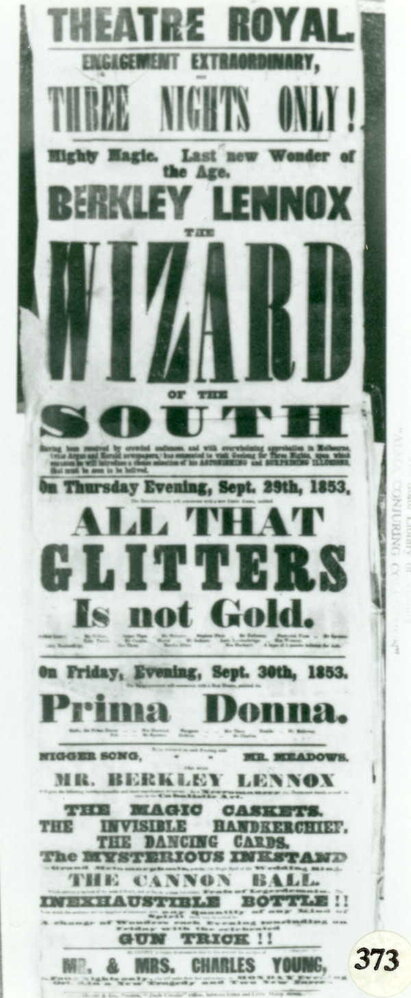

Lennox playbill 1853 from W.G. Alma Conjuring Collection

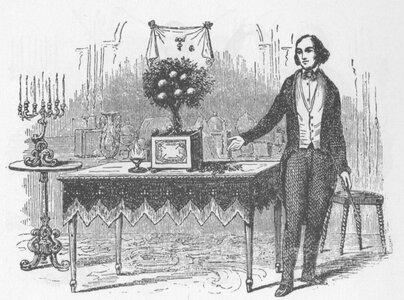

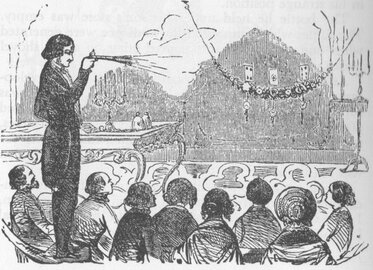

Magic historian, Will Alma, writing in magic collectors’ magazine “Magicol” (6) reproduced a Lennox poster from this time, now held in the State Library of Victoria, along with some letters concerning an application by Lennox to perform. Dealing firstly with the poster, which misspells his name; it comes from the Geelong appearance (the Theatre Royal in Melbourne was not built until 1855) and shows a number of the effects in his repertoire; the Cannon Ball production, the Inexhaustible Bottle and the “Gun Trick” were all tricks seen commonly in the performances of many others from around 1856, though it appears that Lennox was among the earliest, along with Professor Horace Sidney, to present the Bottle trick, and it would come in for particular notice by those audiences which had not previously seen it. These and other tricks such as the Dancing Cards and the Ink Vase Delusion remained in his performance well into 1856. They demonstrate a well-rounded act which seems to have been praised.

Theatre Royal Geelong 1853 Sep 30

The two letters quoted (from Alma’s extensive collection, now in the State Library of Victoria), would have been the first steps in obtaining the necessary permission to present a theatrical act which, at the time, needed to be given by the Colonial Secretary. The Inspector of Police would have made his recommendation prior to granting of the license.

26 Little Lonsdale St. East Melbourne

December 31, 1853

To: Inspector of Police.

Sir, I have the honor to request that you will be pleased to grant me a permission for the purpose of giving a series of drawingroom entertainments, (consisting of Natural Magic and Mechanical Illusions) at the National Hotel (Mr. F.A. Harris proprietor) top of Bourke Street East.

I have further the Honor to state that the room devoted to these performances is on the 1st floor, being quite disconnected with and having a separate entrance from the bar.

The performances to take place between the hours of 7 & 10pm.

I have the honor to be, Sir,

Yr. Most obedient Serv.

Berkley [sic.] Lennox

and, dated, January 6, 1854, in relation to the above:

I have the honor to report for the information of the Commissioner of Police, that the entertainment proposed to be given by Mr Lennox at the National Hotel is of an innocent character and Mr Lennox is a respectable man.

The Hotel is well suited as regards accomodation [sic.] for the purpose and I do not anticipate any evil arise from the request being granted in this case although not friendly to Public House performances in general. [signed by the Inspector, illegible]

Will Alma does not mention having seen any proposed dates for the performances, though he notes that the license was granted on February 11, 1854. It was not unusual for an approval to cover a period of time (months) rather than the performer needing to apply for every show they wished to present. However, in this instance, no advertising can be found to show that any performance took place at the National Hotel.

Lennox had mentioned an impending move to Sydney, while advertising his availability for private entertainments, or to teach the art of magic. He had performed at the Brunswick Hotel, on October 13 and again on November 22 when he promised the addition of ‘two eminent artists’ under the heading “Magic and Music”.

However, after just three months, Lennox then drops from sight for nearly a year and, far from moving northwards to Sydney, his re-appearance is in Launceston, Tasmania, where he and Mrs. Lennox arrived on September 12, 1854 aboard the steamer ‘Royal Shepherd’. Presumably he had remained in Melbourne during the intervening months, though in July an advertisement listed his name for unclaimed mail. It may be that Lennox had not come to Australia with the sole intention of performing magic professionally and was occupied with other business; another consideration is that his wife became pregnant around June 1854. Or, as we shall see, had he taken a step back to obtain some new performing apparatus?

Tasmania 1854

So it was that Lennox sailed across to Launceston where, on September 15 he performed at the Cornwall Assembly Rooms for a large audience, undaunted by poor weather. The Hobart Courier remarked, ‘suffice it to say that whatever was promised was successfully performed … it is difficult to repress the thought that iron safes are scarcely secure, and that buttons afford but slight protection to the breeches pocket [but the performer] invariably restores to their owners the watches or rings he may borrow for the occasion.’

October 14, 1854 Hobart

October 14, 1854 HobartThe Cornwall Chronicle of September 20 favoured Lennox with a highly complimentary review, and in doing so reveals that he had recently received a shipment of new magical props from overseas.

“Mr. BERKELEY LENNOX has ‘astonished the natives’ several evenings past. Human nature is made up of strange materials’ every novelty pleases, and the last is invariably the best. Mr. Lennox has succeeded in gratifying the senses of Launceston audiences (crowded ones too) by deceiving their senses; and blinding their eyes and blunting their imagination. His last trick, “The Inexhaustible Bottle,” is perhaps the most extraordinary. We witnessed the process of this feat closely; the ‘Wizard’ produced an empty bottle, which after cleansing with water, and turning neck down to let the fluid run out, before the audience, he walked around and produced from it, empty as it was, whatever description of spirit any person chose to call for. Brandy, rum, gin, whiskey came from it in bumper glasses as fast as it could be asked for and drank, and the demand was as frequent as it was unlimited. The bottle well supported the character of ‘The Marine’ – it did its work, and was ready to do it again. We left during the imbibing ceremony, when the ‘Wizard’ was complimenting his customers upon their patronage, and regretted that he had that night only a spirit license, but that the bottle was as competent to supply wines as spirits, and that whether a pint or a gallon, or a butt it was immaterial – it was inexhaustible, and could supply any demand for spirits, of any description, if it continued for a month, or time without end.

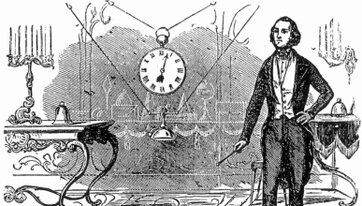

The Inexhaustible Bottle as performed by Robert-Houdin

Altogether the exhibition was unequalled; every trick was ably performed, and as Mr. Lennox varies the programme every night, his performances furnish never ending excitement. At the close he stated, that he had received a fresh supply of tricks by the ‘Queen of the South,’ so that we have necromancy and legerdemain supplied from the mother country in the same manner that merchandise is. Fancy a bill of lading – shipped &c. – to the order of Berkeley Lennox by the good ship Queen of the South – a case of tricks – in good order and well conditioned, &c. – freight being paid in London, &c.

Mr. Lennox gives an entertainment this day, at 2 o’clock, to private parties; after which he will leave for Hobart Town, and has promised to return via Launceston, and give again a few evenings’ entertainment. Every person should witness his rare and unparalleled (in this country) performances; indeed without seeing his trickery, the life of a man can scarcely be said to be fulfilled.”

Such a good review boded well for Mr. Lennox as he approached Hobart, since the last magician in that town was the disastrous Professor Le Berg in 1853, whose brief efforts were described by the press as ‘low, vulgar, and transparent in the extreme.’

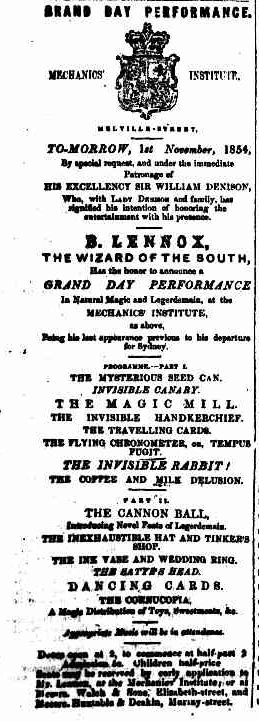

Berkeley Lennox performed locally to Launceston, at Westbury on September 27 and Deloraine on the 28th, before heading South down the main route to Hobart via Campbell Town (October 2), Oatlands (3rd), Green Pons (4th) and Brighton (6th). Billed as “B.Lennox, the Wizard of the South", he opened at Hobart’s Royal Victoria Theatre (now known simply as the Theatre Royal) on Tuesday October 17. A notable addition to his repertoire was “The Cornucopia or Horn of Plenty, being a Grand Distribution of Toys and Sweetmeats.” This would have been Robert-Houdin’s metal “Horn of Plenty”. However there was no indication of the many other Robert-Houdin tricks which would follow in 1856.

We are fortunate that the Courier, on October 20, 1854 gave a lengthy and detailed review of the Wizard’s show, describing the tricks performed rather than the usual uninformative overview.

1854 Oct 31

“THE WIZARD OF THE SOUTH - Mr. B. Lennox’s second entertainment at the Royal Victoria Theatre, last evening, was very numerously and respectably attended, and passed off to the entire satisfaction of every one present. The stage presented a very pretty appearance, being fitted up with very great taste, and displaying to great advantage the elegant mechanism which helps to work the Wizard’s will. The fine band of the 99th Regiment was present, and agreeably filled up the necessary pauses in the execution of the tricks. A novel feat, accomplished by the Wizard, proved him to be an accomplished washer-man, and to the dismay of the gentleman who furnished the handkerchiefs, a first-rate mangler. Borrowing some half dozen handkerchiefs, the Wizard placed them in a vessel full of water, and commenced scrubbing at them in good earnest. Having finished the washing process, he took them out one by one, and held them up before the audience to show that he had not made away with their property. On coming to the last, he showed his skill as a mangler, but cutting a great piece out of the centre of the handkerchief; having accomplished this, he put them in a tin case, under which he placed a fire; in about a minute’s time the cover was raised and the handkerchiefs taken out, not only washed, but ironed and neatly folded – the one which had been so mischievously operated on showing no trace of the scissors. Perhaps the best and neatest trick in the first part of the programme was the transformation of Oats and Barley into Coffee. This was very cleverly managed and, we will venture to say, deceived the eyes of the most sharp-sighted spectator present. Two goblets are filled with oats, and placed upon a plain table without communication with any other object. Two covers, evidently perfectly empty, are placed over the vessels – and what was oats before is coffee now! A third vessel, which we firmly believed to contain bran, turned out some excellent lump sugar, an agreeable accompaniment to the coffee, which was ravenously pounced upon by the pittites, who nearly smothered the unfortunate “[Jenmes? - presumably ‘gents’ ]” in their eagerness to get at a beverage so mysteriously produced.

At the request of several of the audience, the wizard kindly brought forward his Inexhaustible Bottle, and supplied a countless number of “nips” of gin, rum, whisky and brandy; so inexhaustible was the bottle that the audience got fairly tired of committing Oliver Twist’s great fault – of asking “for more” and the wizard having invited fresh applications withdrew, sprinkling the stage with the contents of his mysterious bottle. The second part of the programme proved even more attractive than the first. Here we had travelling half-crowns shooting about from one part of the stage to another, a five pound note burnt before the astonished proprietor’s eyes, restored to its original shape, and extracted from the centre of a candle burning on the table; again, from a lady’s shawl we find tumbling out every variety of bird and animal, showers of bons-bons , toys, papeterie [stationery], the latter being generously distributed amongst the audience; then again we have a mysterious automaton [this was the “Satyr’s Head” trick], who reads the very secrets of your mind, tells cards which have been selected by gentlemen in all parts of the house, and actually shoots them forth from his mouth; he is a mischief maker, too, makes a very young gentleman, with a young lady by his side, in the pit, colour furiously, by hinting that the said youth is not only in love, but is a perfect Grand Turk in his taste for the gentler sex. These are only a few of the very many pleasing tricks, delusions, and feats of legerdemain we witnessed last evening. To describe their effect adequately is impossible – they must be seen to be appreciated; and we trust that Mr. Lennox will find that amount of patronage which his cleverness and liberality merit. His next performance takes place on Tuesday next, at the Theatre Royal, when the programme will be varied, and several very novel feats introduced.”

Lennox’s magic earned him a request by the Lieutenant-Governor of Van Diemen’s Land, Sir William T. Denison, for a special day performance, which was given at the Mechanic’s Institute on November 1, ‘particularly adapted for families and children.’ Despite the effusive commentary by the Courier, they remarked that ‘We wish Mr. Lennox success – he has hitherto been most undeservedly unfortunate; we think, however, we can predict a better state of things on this occasion.’ Lennox was not the only performer to find selling tickets in Hobart a difficult task.

Moving back northwards, he gave a single performance at Davis’s Hotel in Brighton on November 6, November 8 at Campbell Town Assembly Rooms (advertising that his ‘Magic Entertainments have been so highly successful.’) and Longford on November 16.

Creditor’s Dispute

Unfortunately, before his departure from Hobart, Lennox ran into a dispute which would follow him for some time, to his disadvantage. On November 4, 1854, the Colonial Times ran a paragraph stating, “Mr. Berkeley Lennox – The proprietor of the Colonial Times not being disposed to believe that Mr. B. Lennox, the so-called Wizard of the South, intends to depart without paying the account due to this office, in spite of his assertion to that effect, requests that he will call and pay the amount immediately.”

Lennox responded the same day with an advertisement in the ‘Courier’ directed to the Editor of the Colonial Times; but the Times reprinted his letter under the heading “Caution to Newspaper Proprietors” in which they accused Lennox of having flatly refused to pay his account, and saying that his advertisement completes a “very proper exposure:-“

Sir – In reference to the notice concerning me in your edition of Saturday, November 4, 1854, I have the honor to make the following remarks:-

In the first place, the statement made in your journal that ‘I asserted my intention to depart without paying the account due to your office’, is as utterly false as the remarks in your notice are invidious and cruel. You delivered me a most preposterous bill, vis. you charged me two guineas per hundred for slips, which in no other printing-office in the colonies have I ever paid more than fifteen shillings per hundred for.

On receipt of this account, I called at the office, and intimated to yourself, Mr Editor, that there must have been some mistake, begging that it might be rectified, and the amount should then be settled.

On Friday last, you came up to my lodgings and rushed furiously – yourself, Mr. Editor – into a private room where, in the presence of a lady, and of a gentleman (who is willing to testify to the truth of my statements) – yes, in the presence of a lady, you made use of most insulting language towards me, using many expressions which sound very unlike what ought to proceed from the lips of a person calling himself a minister. I then told you that until you had retracted the insinuation you threw out against my public character, I should not settle my account with you.

Hoping that these few remarks will clear me in the eyes of the public from the slur you have attempted to cast upon me, I have the honor to be, Sir, your obedient servant,

B. Lennox, Wizard of the South.

P.S. – Upon your retracting the assertion made in your notice the amount due to you will be paid by Mr. Jones, of the Garrick’s Head Hotel, Liverpool-street.

However offended Mr. Lennox may have been by this unbecoming behaviour, or his own gentlemanly restraint in signing himself “your obedient servant”, the Wizard was on a hiding to nothing against an Editor who had the resources of a newspaper at his disposal. The Colonial Times advertised on November 15 that the “so-called” Wizard had left Hobart and that his ‘account with us is yet UNPAID.’

The Tasmanian Colonist of November 16 took up cudgels as well, commenting that ‘the soi disant wizard has been testing his powers of Legerdemain in victimising the press to some extent, and when applied to for the payment of debts justly incurred by him, treating the applicants with derision and insolence. An individual of this description, who is so essentially dependent on the public for support, should be a little more considerate, if not grateful to the medium through which he is introduced to the notice of the that public. We trust the printers wherever he may proceed, will take cognizance of his conduct here, and maintain the good principle of pay in advance with this slippery specimen of the conjuring genus.’

Ultimately the dispute followed Lennox back up to Launceston. Lennox sent a letter in his defence to the Cornwall Chronicle (the text of which is partially obscured in online copies of the November 25 publication) but in a letter to the Editor of the Cornwall Chronicle on December 2, the slighted Editor of the Colonial Times, George Stewart, put his side of the story (apparently there was also some dispute over whether a smaller sum had been owed or paid to the Hobart Town Advertiser):-

“… When I first called on Mr. Lennox, for the amount mentioned in his letter, he produced no receipted amount, nor did he say it had been paid, but simply laughed at the idea of his doing anything so absurd – he vehemently condemned the Hobart Town Press in general, “The Advertiser” and “Colonial Times” in particular … the next day I called upon Mr. Lennox at the Cornwall Assembly room, when both he, and a lady who I presume was Mrs. L. not only acknowledged the account to be due but promised to pay it next day at 11:00 o’clock; at that hour I again waited on him, when he abruptly stated that he had lost £20 by the previous night’s performance, and it was out of his power to pay. If he had pleaded his difficulties at first, to the proprietors of the Hobart Town Advertiser, I am convinced they would freely have forgiven him the paltry sum … as the matter now stands, he has wantonly damaged his own character….”

And there, finally, the matter rested. From a researcher’s point of view, it can be said that the performer’s life was hardly calculated to be profitable; and we wish just one of those handbills had survived to be reproduced here!

Sydney 1854 - 1855

Berkeley Lennox’s shows in Tasmania concluded with appearances in Launceston and nearby Longford, Westbury and Carrick in late November 1854, finally departing with his wife aboard the brig ‘Emma’ on November 23, destined for Sydney.

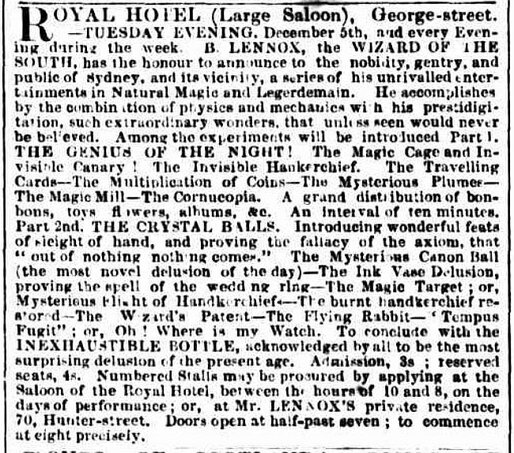

He made his first appearance at the saloon of the Royal Hotel, George Street, on December 5, barely five months since Professor Horace Sidney had concluded a successful season of several months, and with some overlap in their repertoires. Though Lennox was not hiding his name, which is mentioned several times during December, a number of his advertisements refer only to the “Wizard of the South”.

December 5, 1854

The press quickly praised his show and did not make comparisons with Horace Sidney, choosing to mention that he ‘displays consummate proficiency in feats of sleight of hand … gave great satisfaction to a numerous attendance of spectators.’

“Bell’s Life” also made clear that Lennox was a cut above the usual calibre of performer: [December 9]’The entertainments are nightly varied; and their chaste and refined rendering proves that the characters of the wizard and the gentleman are mixed in the person of Mr Lennox. The magic paraphernalia is extremely gorgeous, and every arrangement in keeping with a temple of enchantment.’

December 29 was announced to be the Wizard’s last week at the Royal. As in the previous year, Lennox fades from view for a while, and after a short season at New’s Concert Rooms in Parramatta (January 4 - 10, 1855) he is next noted in the township of Appin, about 75 km south-west of Sydney. He had arrived there with his wife at the beginning of March, but things were about to go wrong. According to the ‘Empire’ of March 17, 1855 Lennox’s first night was admiringly applauded, but as he had not prepared for such a strong reception, he had not brought more than a small selection of his apparatus (perhaps indicating that he had not been touring and performing regularly since December). He left the next day to go and collect some more props with which he planned to give a larger show in Appin. Owing to the crowded state of the van, notorious for their danger on rough roads, Lennox was jerked off at a rut in the road, and his leg was caught by the wheel, breaking both the tibia and fibula of his right leg. By the time of the news report he was said to be progressing well, and almost ready to leave his bed.

Much better news from Appin arrived on April 4 – “Mr. Lennox, the Wizard of the South – whose compulsory stay amongst us, owing to a broken leg, was mentioned in a former communication, is likely to become located here for a still longer period, if not permanently. Although his recovery is complete, and his powers of locomotion perfectly restored, an inducement to further residence here has occurred in the arrival of a near relative, whose advent must prevent the departure, for some time, of himself and Mrs. L. This is no other than a son, who made his appearance on the stage and commenced his part in the first of the poet’s Seven Ages [Shakespeare’s “Seven Ages of Man”] on Saturday night last. Whether this close relationship with a native of the locality will overcome Mr. and Mrs. Lennox’s love of travel, and induce them to settle down amongst us, remains to be seen.”

Apparently not – for on April 21 a “Mr. and Mrs. Lennox and family (3)” were listed departing Australia aboard the brig ‘Venture’, destined for Wanganui, New Zealand. This must have been our Wizard, as no mention is made of him in Australia until July; but equally he does not appear to have performed in New Zealand, and the best guess is that the Lennoxes were taking some time out to look after their new child, and to make a full recovery from the broken leg. Perhaps there were some relations in New Zealand. Later information from Michaele Jeavons, however, reveals that, sadly, a son, Charles Augustus, was born on April 30 1855, and died in Sydney on June 10; he was buried in Campbelltown Cemetery on the June 12. Another son, Frederick George, was born in Sydney in 1856.

When next seen, Lennox was back in New South Wales in the southern tablelands town of Goulburn, July 17, performing at the Goulburn Hotel throughout the week to good audiences. The Goulburn Herald, July 21, considered that “he stands unsurpassed in the lists of fame as a professor of the art of legerdemain … we advise the admirers of innocent, rational, and intellectual enjoyment and astonishment in Goulburn and the neighbourhood not to lose the chance afforded them of witnessing the magical and extraordinary performances of Mr. Lennox, whose clever feats, and gentlemanlike demeanour entitle him to the support of the generous Goulburn public.”

By July 30, the Wizard was a little further south at Braidwood for a highly successful performance at the Court House which was “literally crammed on the occasion, so much so that many persons anxious to witness the magic performances were unable to procure admission. Mr. Lennox was warmly and frequently applauded … his affability, his brilliant talent, his gentlemanly demeanor, and his generous conduct have gained him a host of friends.” (7)

Though there is no mention during August, Lennox may have been appearing in smaller local towns, and by September 6 he was back in Goulburn, but not before Mrs. Lennox met with an accident of her own, nearly being thrown from a buggy when the horse’s bands broke. Fortunately she clung to the horse’s crupper [brace] until with the assistance of her husband and some local men, the horses were brought under control.

Downturn and Resurgence, 1855 – 1856

The circumstances around which Berkeley Lennox’s finances took a turn for the worse are unclear, and from this time we have to speculate on his intentions, activities and whereabouts.

On October 24 and 25, 1855, Lennox appeared at the Rose Inn, Maitland, in New South Wales’ Hunter Valley. While his repertoire was essentially the same, the second part of the show began with “the surprising feat of The Mysterious Lady”. This was Mrs. Lennox, and it was a form of two-person clairvoyance demonstration. Lennox also donned fancy robes to present his “Chinese Delusions”, which were his usual tricks in a new guise.

On October 31 he was advertising to perform at Brackenreg’s Hotel at East Maitland for November 1, Holdstock’s Hotel at Raymond Terrace on the 3rd, and back to the Rose Inn at West Maitland for the 6th. On November 8, a grand benefit performance was scheduled to raise money for the Maitland Hospital.

However, there was also an announcement that, at the nearby Newcastle Court House, the Sherriff would sell two good draught horses and one excellent cart, the property of the defendant in the Supreme Court case of Heape v. Lennox (the details of which cannot be located). Confirmation that this involved Berkeley Lennox came a week later when the Sydney Morning Herald listed an Insolvency notice for “Berkeley James Lennox, of West Maitland, gentleman. Liabilities £220 18s 10d. Assets, personal property £33, outstanding debts £23 10s, total £56 10s. Deficiency £164 8s. Mr. Perry, official assignee.” In the months to come there would be regular notices of meetings to assess Mr. Lennox’s current state of insolvency and the claims against his estate.

Bankruptcy, however, seems to be a wholly flexible beast, and Lennox continued to advertise both the Maitland Hospital show, and his own Benefit performance on November 10, 1855, being ‘positively his last performance in Maitland’. From November 6, though, (a Benefit night for the Mysterious Lady) he reduced the price of admission to 2s 6d. for general admission. The celebrated Gun Delusion was again included in the programme, “allowing any person to fire a marked bullet at him, which he will catch with his teeth.” The Maitland Hospital thanked Lennox in print for raising he handsome sum of £24 2s. 6d, wishing him and his ‘amiable wife, who so ably assisted you in her extraordinary performance’ every success and prosperity.

Lennox had another minor run-in with a Mr Snape who wanted payment for some printing, but had not delivered the goods, and Mrs. Lennox sent him away; Snape accused Lennox of being a ‘swindler’, and Snape was ultimately fined in Maitland Court for inciting a breach of the peace.

Performing at East Maitland on November 21, and Paterson on the 24th, Berkeley Lennox made his way back to Sydney where, on December 1 it was reported that one creditor’s claim for £2 10s was proved, but the insolvent was allowed to retain his furniture, wearing apparel and (fortunately) his tools of trade.

Continuing to find his way free, Lennox now appeared at the Prince of Wales Theatre, a huge venue in Castlereagh Street capable of holding several thousand audience. Alongside him on a variety bill was Pablo Fanque, notable British Circus personality, tight-rope dancer and equestrian whose name has been immortalised on Beatles’ album “Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band”. By the account of “Bell’s Life in Sydney”, December 8, the combined entertainment was the great attraction of the week, and much was made of the “Mysterious Lady” whose act was described in some detail:-

“… A Mysterious Lady, professing the gift of clairvoyance, whose divinations were truly startling. Concealed behind a screen (said to be eye-proof, and we have no reason to doubt it) at the back of the stage with her back to the audience, she described with the greatest minuteness every article handed to the Wizard by parties indiscriminately I pit and boxes, and that without a single error, or the slightest hesitation.”

News of the fall of Sebastopol, following a protracted siege by Britain and her allies against the Russians in the Crimea, reached Sydney and December 12 was awash with celebrations and a general holiday, in which celebrations Lennox and Fanque took their part. Lennox then returned to the Royal Hotel in George Street, under the immediate patronage of the Governor-General and family. He and the Mysterious Lady played only December 17 in the hotel’s new Concert Hall, announcing that this was his last night in Sydney, though more shows did eventuate. A single night at Windsor on December 22 saw out the year, after which began a series of activities which create something of a puzzle.

Final Year - 1856

Lennox continued to perform in the early new year of 1856, at Wollongong on the south coast for the nights of Saturday January 5 and then January 7-9 at the Royal Marine Hotel New Concert Hall. Mrs. Lennox was earning some extra money by offering psychic consultation for a fee. Plagued once again by continual rain, his first night was poorly attended but well received. Moving to Kiama on the 24th, and Dapto on the 28th, Mr. Lennox was apparently planning a new venture in Sydney.

January 7, 1856

January 7, 1856February 9 saw the Wizard open at the Royal Polytechnic on the corner of Pitt and Bathurst streets; an institution of public enlightenment, more than a theatre. The Polytechnic, an article in the previous year had bemoaned, had been showing exhibitions of dissolving views and had “expensive apparatus calculated to illustrate almost every branch of natural philosophy, and many of the arts and sciences known to the present generation” but from “want of proper support” it was struggling to survive. Possibly Lennox made a good deal with the proprietor and, when he opened, it was almost as a support act to his imported minstrel troupe, “Lennox’s Company of Female American Serenaders”. Certainly the appearance is that Lennox was attempting to move into an entrepreneurial role and to bolster his own up-and-down fortunes. “Bell’s Life” [February 9] gave Lennox credit for his boldness in bringing out a minstrel troupe so soon after the departure of the highly successful Backus Minstrels, and ranked his ladies as being ‘far above the ordinary run of Ethiopians, and the crowds that nightly visit the Polytechnic attest powerfully to the novelty of the attraction.’

Newspaper commentary a week later was not so confident about the size of the audiences, and by February 20 the Female Serenaders are no longer mentioned; except that a Miss Montague advertised that she had not broken her engagements with Lennox; rather he had not paid her salary, and she was instituting proceedings in the Courts of Requests for recovery of the same. Lennox took a Benefit night on February 25, and assisted with another performer’s benefit a few days later, playing the role of “Cox” in the comic play, “Box and Cox”.

From this time on, until October 1856, the whereabouts of Berkeley Lennox and his wife became a mystery, He is not mentioned at all in the press, and no record can be found of a shipping departure from the country. Charles Waller was of the opinion that Lennox had made a sufficient success of his previous performances to venture back to Europe and purchase a raft of very grand and expensive new magic apparatus; and he certainly did buy new equipment. The puzzle to be solved is whether he travelled overseas, at a time when a return journey would have taken fully six months by sea, and where he obtained the money to buy his equipment, for on the face of things, his shows had been financially unsuccessful and unlikely to sustain him for much longer. Also, had he known how brief would be his final season, would he have gone to such lengths? The only indication we had that Lennox may have travelled, is a comment from the Melbourne Age, November 6, 1856, that he had ‘lately arrived from Paris with a well-earned reputation’; but this sounds very much like a man in a new city trying to start over.

Thanks, however, to Ms Jeavons we have the likely solution to the missing period, and the following paragraphs are the results of her research. It appears that Lennox, until October, had taken on work as a private detective.

WATER POLICE COURT. Tuesday. Thomas Allen, John Goodwin and Jeremiah Reardon were charged with having, at Cremorne Gardens last night, assaulted Acting-Sergeant O'Keefe, and Constables Lennox and Baskett, belonging to the detective force. The Sydney Morning Herald Wed 9 Apr 1856

TAKING CARE OF THE TRINKETS. ... From information that he had received in reference to this matter, that distinguished scion of the House of Richmond, detective Lennox, repaired to an establishment of indifferent repute in Kent-street, where he found Patrick Harney and a Miss Elizabeth Somers sitting together on a bed, and in their possession, sundry monies and the missing brooch. Bell's Life in Sydney and Sporting Reviewer Sat 30 Aug 1856

THE TOPICS OF THE WEEK.... There is an old saying, "Give certain men rope enough and they will hang themselves". Constant success, considerable cunning and a large quantity of official favouritism have rendered the Detective Police - the pupils of the Australian Vidocq School - utterly careless of public opinion and equally so of the sharpness of teeth with which they bite the hands that feed them. So carefully laid are their plans, so well matured their actions, so strong the systematically favourable evidence they can summon up at a moment's notice, that it is a Herculean task to prove their arbitrary exercise of power. It does occasionally happen they are caught tripping and successfully brought to book. An instance of this detective virtue meeting its reward occurred at the Central Police Office on Tuesday. One Berkeley Lennox, detective, charged William Berry with having assaulted him in the execution of his duty on the previous night. The evidence of Lennox and a professional friend was, of course, conclusive, and Berry was fined twenty shillings. But, luckily for Berry, he was enabled, by indisputable testimony, to turn the tables on the defendant.... The People's Advocate and New South Wales Vindicator Sat 4 Oct 1856

(The crime-solving group of so called policemen of the Australian Vidocq School, would have been members of the Vidocq Society, so named for the father of modern criminal investigation, Eugène François Vidocq (1755-1857), a self-reformed French criminal who turned a young life of fraud, theft, and womanizing into a crime-fighting legacy. He became the founder and first director of the crime-detection Sûreté Nationale, as well as the head of the first known private detective agency, and is considered to be the father of modern criminology and of the French police department.)

(The testimony referred to in the previous article, was provided by Mr. Daniel Eagan, J.P. His evidence was that he had witnessed the initial altercation between Lennox and Berry, asserting that Lennox had deliberately tripped Berry, and that later that same evening he had also witnessed Lennox follow Berry and strike him several times, without provocation. The Magistrate reversed his original finding and Berkeley was fined forty shillings, or in default, seven days imprisonment.)

POLICE PICKINGS ... The present case arose out of one for assault committed on the 29th of September last, by one Berkeley Lennox, otherwise known as Lord Stuart Lennox, a ce qu on dit {so the story goes}, a nephew to the Duke of Richmond, who was at that time attached to the distinguished corps of the Sydney detectives, and for which the said gentleman, nobleman, or policeman, as the case may be, was mulcted in the amount of 40s. On the occasion of the assault case being heard, the present prosecutor, Daniel Egan, Esq., J.P, M.P., and we don't know how many other P's, gave evidence to the effect that he had seen the assault committed by Lennox, while the detective Andrew Smith swore that no assault was committed.

Bell's Life in Sydney and Sporting Reviewer, Sat 8 Nov 1856

Bell's Life in Sydney and Sporting Reviewer, Sat 8 Nov 1856

=====

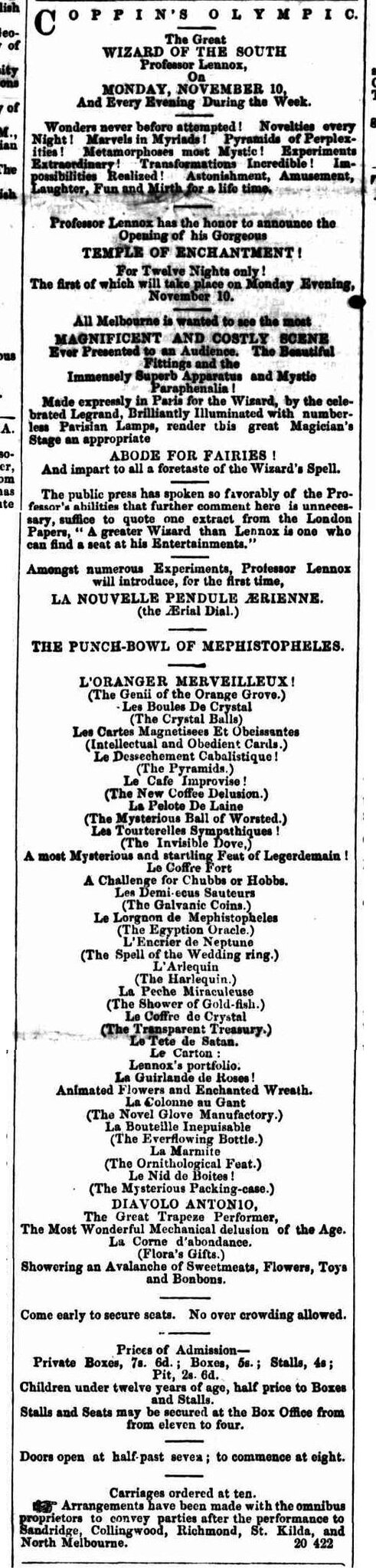

On October 22, the steamer ‘Yarra Yarra’ departed Sydney for Melbourne with Mr. and Mrs. Lennox aboard, and on Monday November 10, the Great Wizard of the South, Professor Lennox, hit Melbourne with a blast of bluster and a stage full of incredible equipment.

The Olympic Theatre, on the corner of Lonsdale and Exhibition Streets (now the site of the Comedy Theatre) had only been open for eighteen months under the direction of George Coppin. Determined to make a splash, Lennox advertised in a bombastic style previously foreign to his promotions:

“The Great

WIZARD OF THE SOUTH

Professor LENNOX

On Monday, 10th November

And Every Evening During the Week.

Wonders never before attempted! Novelties

every night! Marvels in Myriads! Pyramids

of Perplexities! Metamorphoses most Mystic!

Experiments Extraordinary! Transformations

Incredible! Impossibilities Realized!

Astonishment, Amusement, Laughter, Fun

and Mirth for a life time.”

November 10, 1856

Lennox made a point of highlighting the expensive and gorgeous apparatus and settings for his new “Temple of Enchantment” which he stated were ‘made expressly in Paris for the Wizard, by the celebrated Legrand.’ This does not confirm that he travelled to Paris himself but, as Charles Waller suggests, it may reveal the name of a manufacturer who was busily engaged in copying all of Robert-Houdin’s finest tricks and automata, for sale to anyone who could pay.

The Wizard had certainly not stinted himself. Amongst the fancy new French titles given to his former repertoire were numerous showy new tricks, all from the programmes of Jean Eugene Robert-Houdin, the ‘father of modern magic.’ Indeed, many of his earlier tricks were also of Robert-Houdin’s invention or updated presentation.

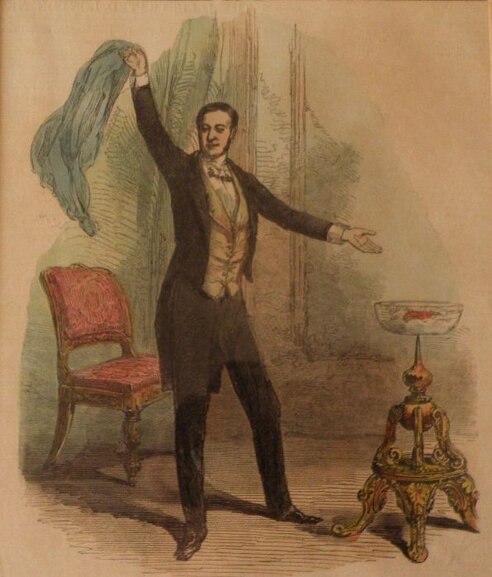

The illustrations shown here are from Robert-Houdin’s autobiography, Confidences d’un Prestidigitateur (1858).

Aerial Dial – A transparent clock dial, hung between two light cords, moved to a chosen time on the magician’s command, and a bell beneath the dial sounded.

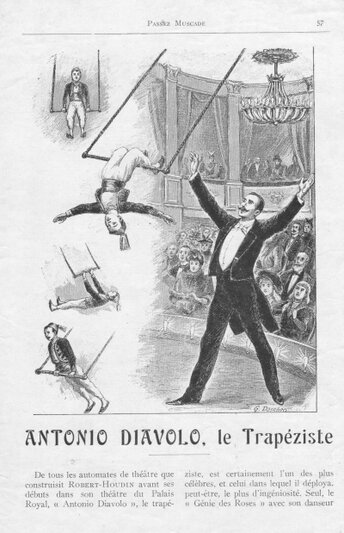

Antonio Diavolo, from Passe Muscade magazine.

Diavolo Antonio (or Antonio Diavolo)– One of Houdin’s most amazing mechanical figures, the little gentleman could sit and swing on a trapeze, bow to the audience and perform acrobatics, swinging by both his hands and legs, finally dropping into the arms of the magician, who had apparently had no connection with the figure.

Lovingly restored by magical artisan, John Gaughan, the original figure can be viewed in performance at:

The Genii of the Orange Grove –

a marvel of mechanics. A borrowed handkerchief was magically passed into the centre of an egg, then a lemon, then an orange; finally vanishing. A small orange tree was brought to centre stage, gradually revealing blossoms, then growing oranges in view of the audience. The final orange split apart, revealing the handkerchief, and two butterflies took corners of the ‘kerchief, fluttering above the tree. A modified recreation of this effect can be seen at:

The Harlequin – An automaton figure, companion to ‘Antonio Diavolo’. A figure of a little man would jump out of a box, dance, do the splits, smoke and blow a whistle.

Enchanted Wreath – A routine in which three handkerchiefs and watches were apparently destroyed, three playing cards chosen, all appearing on a suspended garland of flowers, upon the magician’s gunshot.

Shower of Gold Fish – Appears to be the “Marvelous Fishing” trick in which a large bowl of fish was magically produced underneath an empty cloth.

Lennox’s Portfolio – A thin portfolio is placed on two trestle legs, and from it is produced a vast array of birds, hats, cookware and (in the original version) a live boy.

Transparent Treasury – Borrowed and marked coins visibly appear in a crystal casket suspended over the stage by fine silk cords.

The mystery remains; how did Lennox manage to pay for such an extravagant display of magic. Did he have an independent income, and if so, why would he have declared himself insolvent a year prior? Did he perhaps borrow from family or friends?

For all his drive, promotion, and expense the gamble does not seem to have paid off for Lennox. The Olympic Theatre season had been advertised to run for twelve nights from November 10, but within a week, Lennox was promoting heavily reduced ticket prices, a giveaway prize of a gold watch, and a change of programme.

The ‘Age’ made some complimentary remarks about his performance, and the Benefit night which he conducted for the Benevolent Asylum on November 18, but reading between the lines it can be seen that attendances were not good:- “We trust that for the sake of Mr Lennox, as well as for the benefit of the Asylum, the public will heartily honor his kind intention by attending in large numbers.”

While the season ran its full course, with a Benefit for the Wizard on November 22, there seems to have been an entire lack of support from the public. Will Alma states that the unfavourable state of the weather had again played its part. (8)

As December began, Berkeley Lennox moved his Temple of Magic across to the Cremorne Gardens, a pleasure garden on the banks of the Yarra River at Richmond, and another of George Coppin’s projects, until he was bankrupted in 1863. In the ‘Pantheon’, which the ‘Age’ reported to be ‘filled from end to end by the satisfied spectators of Professor Lennox’s admirable feats of magic and legerdemain’, Lennox continued to show until December 13, 1856.

In early January of 1857, Berkeley, Marrianne and Frederick George sailed aboard the “Prince of the Seas”, bound for England via Callao, Peru. The last thing we know of Berkeley Lennox is his death in 1857, at the tragically early age of 28, barely six months after his final Australian performance.

Two brief reports in British newspapers stated:- “DEATHS - At Lima [Peru], on his passage to England, on the 9th June, aged 28, BERKELEY LENNOX, Esq., eldest son of the Lord Sussex Lennox and grandson of the late Duke of Richmond.

Two brief reports in British newspapers stated:- “DEATHS - At Lima [Peru], on his passage to England, on the 9th June, aged 28, BERKELEY LENNOX, Esq., eldest son of the Lord Sussex Lennox and grandson of the late Duke of Richmond.

The short life of Berkeley Lennox leaves us with admiration for the drive and talent of such a young man, whose productive years were spent in the service of audiences in this country.

REFERENCES:

(1) http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C13287642. Page 71 of record WO 76_238

See also Burke’s Peerage, 2003 volume 3, page 3336.

(3) Lord Sussex Lennox - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lord_Sussex_Lennox

and a portrait at Portrait http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portraitLarge/mw144407/Lord-Sussex-Lennox?LinkID=mp92931&role=sit&rNo=0

(4) The Annual Register of the year 1828, London.

(5) Hobart-Town Courier, December 29, 1827

(6) Magicol, magazine of the Magic Collectors’ Association. Issue No.65, November 1982

(7) Goulburn Herald August 4, 1855

(8) Will Alma’s ‘Magic Circle Mirror’, April 1972.