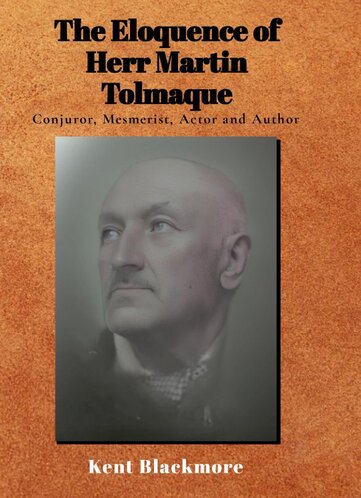

The Eloquence of Herr Martin Tolmaque

Conjuror, Mesmerist, Actor and Author

INTRODUCTION

When Harry Houdini was here in 1910 he told me he had found Tolmaque’s grave in the Melbourne General Cemetery.

– Charles Waller, ‘Magical Nights at the Theatre’.

Herr Martin Beaufort Tolmaque was a conjuror, escape artist, mesmerist, actor, anti-spiritualist, phrenologist and writer. He had some fame as a magician, and Houdini saw him as an important precursor to his own feats of escapology and spirit debunking. In Australia, however, his main claim to attention was to have been incarcerated, multiple times, in the New Norfolk Hospital for the Insane, from which experience he wrote a series of blistering newspaper stories which resulted in his complaints being examined by official commissions of enquiry.

Houdini was, in fact, wrong. Tolmaque was not at Melbourne Cemetery, but lying in a pauper’s grave at Hobart, Tasmania. How he got there from his birthplace in Hamburg, Germany is a tale of adventure, disappointment, and sad decline. This is the true history of the eloquent Herr Martin Tolmaque.

Chapter One - Origins and Early Days

No doubt it is a matter of perfect indifference to my readers as to where I was born… – Tolmaque, ‘The Struggles of Life’ Chapter I"Disdaining all mechanism or apparatus, which he says he never used or ever will use in his entertainments, he relies solely upon his wonderful skill in sleight-of-hand to amuse and mystify his audiences. There have been professors of magic who have made greater show on and off the stage than Herr Tolmaque, but there has not been one as yet who succeeded in giving a whole evening's entertainment alone and unaided either by apparatus or assistants more or less in number. Conjurors, so called, there are plenty, and every raw amateur possessed of a few tin bricks, a magic wand, and unbounded cheek, comes before the public as a great and unrivalled professor; but such conjuring as Herr Tolmaque shows us can only be the outcome of years of practice, and a special aptitude for the business.

…True, both Anderson and Heller, as well as Jacobs and others, have performed similar feats, but those gentlemen had elaborate apparatus and assistants to help them, whereas Tolmaque is entirely unaided, except by his own marvellous dexterity and almost superhuman skill. As a phrenologist, too, he occupies a front rank.”

- Bendigo Advertiser, March 27, 1883

From the start it must be stated that we do not have a complete life picture of the magician who called himself Martin Beaufort Tolmaque. His origins are obscure, his personal history sparse, and his public record limited to his appearances in theatres, rather than the many private entertainments which formed his livelihood. Histories of magic mention Tolmaque almost in passing, in relation to his rope escape feat, and his opposition to the pseudo-spiritualists, the Davenport Brothers.

The discovery, then, of thirty-eight autobiographical stories written under the heading ‘The Struggles of Life, or the True Adventures of Herr Tolmaque’ and nine more tales written for the newspapers, adds enormously to our understanding of this little-document magician, placing him amongst one of the more talented sleight-of-hand performers of Britain in the mid-1800s.

But away from the theatrical life, Tolmaque’s story is dominated by his sad decline and end. The ten chapters he wrote for the press in 1885, titled ‘The Treatment of the Insane, or Nine Months in the Lunatic Asylum’, give us an insight into the true struggles of this solitary and restless man. These introductory chapters are designed to fill in dates, places and facts about Herr Tolmaque, such as can be found via public records. The reader will then find Tolmaque’s own writings reproduced later.

These early chapters are designed to fill in dates, places and facts about Herr Tolmaque, such as can be found via public records.

What little we know of magician Martin Beaufort Tolmaque’s origins comes mostly from his own words, with a few minor clues from documents towards the end of his life. Firstly, part or all of Tolmaque’s name may be genuine or, almost certainly, something adopted by himself. The family name ‘Tolmaque’ does not seem to be a common one, although ‘Tollemache’ can be found as an old British name, and ‘Télémaque’ in the French, originating from the son of Ulysses, Telemachus. In 1884, his admission to the New Norfolk Hospital indicated his nearest kin to be a David Solomon of Hamburg (brother). In his story ‘The Secret Revealed’, Martin remarks “I … exponent of so-called spiritualism, and lineal descendant of King Solomon…”

In his own words, “I am known as Herr Tolmaque or Professor Martin Beaufort Tolmaque. I have borne this name since the commencement of my professional career, 23 years ago, I have borne it for weal and for woe, and I am not at all inclined to change.” (0)

He also states that “I am a native of Altona a portion of Schleswig-Holstein, tributary to the King of Denmark, but now as everyone is aware, a branch of North Germany”. This is modern-day Hamburg, and although a couple of third parties claim him to have been French (1), his German origins are supported by his use of the term “Vaterland”; his recorded religion is show variously as either ‘Hebrew’, but more often and perhaps more accurately as ‘Lutheran’ on his admission documents (2). He makes reference to Justus Freiherr von Liebig, the originator of Oxo meat extracts, as “a countryman of mine.” As well, in 1878 he was advertising as a tutor in the German language.

His hospital admission papers, across a number of years, and his death register, are in approximate agreement that his date of birth was c.1834-35.

According to his own account, young Martin lost both his parents at the age of thirteen (c.1848), and was then sent to work in a commercial office, which he detested, and then further off into the countryside, during which time he lost all his money. Through an acquaintance he determined to head off to England, finding himself in Liverpool where again, he said “the hateful drudgery of business became again insupportable, and I resolved once more to seek adventure wherever it might be obtained.”

From these short excerpts, Martin’s character is already becoming clear. From earliest days he was a restless adventurer, unable to settle, yet full of ideas to make his way in the world.

Memoirs and Reliability

The stories which Martin Tolmaque wrote for two Australian newspapers in 1877 are not detailed in the sense of naming dates, nor are they a complete autobiography; by his own admission he skips over periods of many years during which he finds nothing of interest to relate. Our main consideration, then, is whether his stories are reliable as historical fact. Magicians are notorious for either exaggerating their adventures, or inventing them completely. In Tolmaque’s case, however, we may have some confidence in his tales. Where he refers to a city, or a theatre, or an identifiable date or person’s name, these can frequently be confirmed by other sources (newspaper advertising or reviews in particular). His anecdotes are not so outrageous as to be regarded as fiction, and although some are romanticised they can be found to have a basis of truth – his much-vaunted association with the Duke of Northumberland, for instance, can be traced and verified. Some other stories, concerning his adventures with gamblers and thieves, cannot be so easily investigated, but again they are not so blown out of proportion as to be pure fiction. Many of the tales are told against himself. So, we can regard Tolmaque as giving us a reasonably reliable insight into his world. We can say, however, that his chronology is poor.

1860s – The Indian Rope Feat

Returning to his memoirs, we learn that although Martin had early training in both English and French, he soon discovered that his schoolboy English was of little use to him, and he threw himself into mastering the language to such a degree that his German accent was completely submerged; and, as a fledgling actor he grew to love Shakespeare with a passion that is reflected in his constant quoting of the Bard (and a degree of pride in being able to do so). We bypass many years before Tolmaque emerged before the public, jumping from one unsatisfactory job to another:

“Again, I skip over a considerable period, during which I was variously occupied, trying many professions but caring for none. First, German correspondent for a London periodical, then sub-editor of another, a deeply-religious paper, the proprietor of which was magnanimous enough to allow me to act as sub-editor, advertisement-collector, and manager, and his generosity extended to the awful sum of 15s. per week, for which sum I had to attend the office from 9 in the morning till 6 in the evening, with the exception of one hour for dinner, which said meal I usually took at the hospitable board of ‘His Grace Duke Humphrey’ [idiom –‘to go without dinner’ - The phrase refers to the story of a man who, while visiting the tomb of Duke Humphrey of Gloucester, was locked in the abbey - and thus missed dinner.]

I am not romancing, but stating a real fact. Next I tried my hand at amateur acting, with more or less success (chiefly less); then I turned interpreter and clerk, in which capacity I went the round of nearly twenty different establishments, and eventually I became (quite by accident) an exhibitor of natural curiosities in the shape of a white-headed or albino family. Then came more literature in the shape of translations from the German, chiefly Christmas stories, and such like; then the stage; and finally conjuring…”

If he was acting prior to 1862, his name is unknown to history. It was on June 1, 1862, that Tolmaque is first noted, at the Royal Cremorne Gardens at Chelsea (3), during the opening of the new International Hall, holding 7,000. The Gardens, a place for promenading, novel entertainments, dancing and banqueting, would in the 1870s feature such magicians as Charles De Vere and Alfred Silvester. They were filled with attractions but did not rate the most respectable reputation. Tolmaque is mentioned amongst a host of gymnasts, performing elephants, comic dogs and a French Giant – “First appearance of Mr. Tolmaque, who will introduce his marvellous Indian Rope Feat, which has hitherto baffled the ingenuity of the most scientific men.”

The Indian Rope Feat may or may not have been Tolmaque’s own discovery, but he appears to have been the first to make it a featured presentation in front of the British public, and many others copied him in later years. Not to be confused with the legendary magic trick involving a small boy climbing a rope and disappearing, Tolmaque had become a very early example of the ‘escape artist’ and his trick was to be securely bound with a length of rope from which he would then free himself. The rope was said to be nearly a hundred yards long, and he would be tied while sitting in a chair, “so tightly that the ropes mark his flesh … knotted round his feet, pinioning his arms and enfolding his body so that to move an inch seems impossible … and after a moment or two of concealment behind a screen the performer should leap out upon the stage as free as air.” (4)

That was the common description of the rope feat, which is now known as the 100-foot Rope Escape. However, in July there was a description of the performance which varies inasmuch as multiple ropes were used; and this makes a difference in the escape method used by Tolmaque. A series of short ropes could add greatly to his difficulties.

“Mr. Tolmaque, who appeared in the character of an Indian slave … invite any person or persons in the audience to bind him to a chair in any way they chose, and that he would in a few minutes release himself from the bonds. The whole apparatus on the stage consisted of a broad plank, raised about three feet high, on which was placed a chair; also, several pieces of rope; and a cotton covering stretched on a frame, very much in the form of an extinguisher, about four feet in diameter, and seven or eight feet in height. Four or five persons from the audience stepped upon the stage … proceeded to bind his body, legs, arms with the coils of rope. Before the operation was completed, a man-of-war’s man belonging to the ‘Vigilant’ jumped upon the stage … took up a rope, and eyed the victim with a professional glance to satisfy himself that the work had been properly done. Having added one rope more to the half dozen already used … the covering was put on … in rather less than four and a half minutes the covering was thrown off, and Mr. Tolmaque was seen sitting with the coils of rope lying at his feet, and apparently without having undergone much exertion … Mr. Tolmaque is a young man of slender build, middle height, and his general appearance does not indicate great muscular strength…” (5)

This escape pre-dates the escapology of Harry Houdini by many years (he was born in 1874), and does not seem to have been inspired by the antics of the pseudo-spiritualists, the Davenport Brothers who were still in their early career in America.

Of its origins, author Thomas Frost, in his book ‘Circus Life and Circus Celebrities’ (1875) claimed that the Indian juggler Ramo Samee, considered to be the first modern professional juggler in England, brought the trick to that country when he arrived as early as 1818, and communicated its secret to the (ostensibly Chinese) jugglers known as the Brothers Nemo. According to Frost they were not overly impressed by the rope trick, but a source (13) does credit the older brother with having performed it, apparently well prior to Tolmaque, at Vauxhall Gardens. This claim seems unsupported, the brothers only appearing in England from 1863. The brothers certainly joined in the anti-Davenport furore of later years.

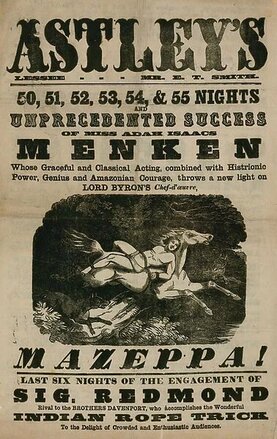

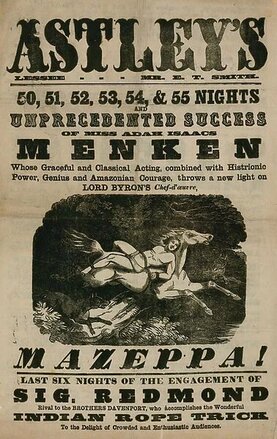

Frost, sadly, ignores Tolmaque and credits Professor Redmond as the first exhibitor of the Indian Rope Trick; whereas Redmond actually followed Tolmaque, who was acknowledged by the contemporary news media to have been the first. Frost’s information may have arisen from the fact that Redmond had performed for Astley’s Circus.

Frost: “Another performance which excited a large amount of public attention, partly through the mystery in which the modus operandi was enveloped, and partly by reason of the excitement previously produced by the Brothers Davenport’s exhibition of alleged spirit-manifestations, was the ‘rope-trick,’ shown first by an expert performer named Redmond at Astley’s, and afterwards at most of the music-halls. The performer was enclosed in a cabinet about three feet square, and five or six feet high, with a door facing the spectators, and provided with a small aperture near the top. In a few minutes an attendant opened the door, when Redmond was seen within, securely bound in a chair. The spectators were allowed to satisfy themselves that he was bound as securely as if a second person had bound him, and then the door was closed. In a few moments he rang a bell, then he showed one hand at the aperture; in a few seconds more he began to beat a tambourine, and in a minute and a half from the time he was shut in the door was opened again, and he walked out, with the rope in his hands. This performance proved so attractive that it soon had many imitators, but none of them did it in so genuine and puzzling a manner, or displayed equal dexterity in its exhibition.

The trick was not original, but it was new to the public, or at least to the present generation. I have heard it called both the American rope-trick and the Indian rope-trick, but the former name may have been derived from the similar performance of the Brothers Davenport, who pretended to be passive agents in the business, and to be tied and untied by spirits. Long before the pretended spiritual phenomena were ever heard of, the rope-trick was in the repertoire of the famous Hindoo juggler, Ramo Samee, who performed at the Adelphi and the Victoria some forty years ago. The manner of its performance is said to have been communicated by him to one of the Brothers Nemo, who thought so little of it that he never exhibited it until the public mind had become excited by the tricks of the Davenports and the antagonistic performance of Redmond. Next to the latter, Nemo was the best exhibitor of the trick that I ever saw; but that is not saying much, for most of them were so incompetent to perform it that the effect produced by its exhibition by them was simply ludicrous. I remember one of them—I will not mention his name—complaining when he found that he could not release himself, that he had not been treated as a gentleman by the person—one of the spectators—by whom he had been bound; and another, that he had been tied so tightly that the rope hurt his wrists, and stipulating, on another occasion, that he should not be tied tight!

The peculiarity which distinguished Redmond’s feats in a remarkable manner from those of his imitators was, that he not only released himself from the rope in less time than was occupied in binding him, whoever the operator might be, but bound himself in a manner that baffled the skill and exhausted the patience of every one who attempted to unbind him. I was present one evening at the decision of a wager which had been made by a West-end butcher, that he would unbind Redmond in a given time, the tying up being done by Redmond himself. The performer entered the cabinet, carrying the rope, and was shut in; in less than two minutes the door was opened, and he was seen bound, hand and foot, to the chair on which he was sitting. The butcher immediately set to work, several gentlemen standing around, with their watches in their hands, surveying the operation with the keenest interest. It was very soon seen that the butcher was at fault; he could not find either end of the rope. He sought in Redmond’s boots, up his sleeves, inside his vest, but the rope seemed endless. He fumed, he perspired, as the seconds grew into minutes, and the minutes swiftly chased each other down the stream of time; but no end could he discover. Time was called, and the butcher’s wager was lost. Redmond was then enclosed in the cabinet again, and in less than two minutes he was free.

The secret of this trick is unknown to me, but I was not long in discovering that the mere untying by a person of a rope which has been bound about him by another is, however securely the rope may be tied, a very simple matter. It does not follow, however, that the feat can be performed by every one. The operator must possess good muscles, sound lungs, small hands, and strong fingers. If he clenches his hands, raises the muscles of his arms, and keeps his chest inflated during the operation of tying, he will find that his work is half done by the simple process of opening his hands, relaxing the muscles of the arms, and restoring the natural respiration. If the wrists are bound together without being separately secured, the releasing of one hand frees the other by the slackening of the rope; but the operator is thought to be more securely tied when the rope is tied with a knot about the right wrist, and then passed round the other, both drawn close together, and a second knot tied. In this case, the right hand must be drawn through the hempen bracelet by arching it lengthwise, and bringing the thumb within the palm, so that the breadth of the hand shall very little exceed that of the wrist; and this operation is greatly facilitated by a smooth, hard skin. With the right hand at liberty, there is little more to be done; for a skilful and experienced manipulator finds it easier to slip out of his bonds than to untie the knots which are supposed to increase his difficulty. Any man possessing the physical qualifications which I have mentioned ought to be able to liberate himself, however securely he is tied, in a minute and a half.”

The Rope Feat, however, did not take off at once. Martin wrote of his Cremorne Gardens debut, “although the Press spoke highly of it, it created no very great excitement; the chief cause of which I had sense enough to foresee at once.” His solution was to daub himself all over with makeup in the guise of an Indian native, which must have been singularly inconvenient, but it gave him a hook on which to hang the presentation of his trick. As a feat of escapology Tolmaque, still in his late twenties, needed to learn how to make it exciting and sensational, though he was on the right track by presenting it as a challenge to the audience. Houdini, years later, made his reputation with the ‘challenge’ aspect of escapes, and he would never make an escape ‘apparently without having undergone much exertion’ – the audience needed to believe that the escape artist had been in peril and had given every ounce of his strength to free himself. This impression of exertion Tolmaque soon adopted, and he was favoured by a useful commentary sent to the ‘Field’ newspaper by surgeon and zoologist, Francis Trevelyan Buckland (who later repeated his story in one of his books.) (6)

“Having been requested to be present at, and give my opinion on, a performance which I hardly know whether to call a feat of strength or a feat of ingenuity, I was challenged to tie the performer of this feat into a chair with rope in any way, and with any number of knots, in such a manner that he could not get loose. Accordingly I presented myself at the time and place appointed, and, half suspecting some sleight-of-hand trick provided myself with several yards of very strong rope. The performer — an intelligent and rather good-looking young man, set himself in a common wooden kitchen chair, and presented me with his rope. I asked him if he had any objection to using my rope? “None, whatever,” was the reply; “and you may tie me in any way, and with as tight knots as you please.” Having examined the chair to see that that was all right and above-board, I proceeded first to pinion the arms of the young man, who sat down in the chair; pinioning them ‘Jack Ketch’ fashion behind his body. I then lashed them (tied as they were) tightly with many knots and twistings to the back of the chair. I then tied his wrists tightly to the legs of the chair, pulling the ropes, I fear, cruelly tight, as the man afterwards shewed me where I had cut the skin; but he did not complain of this a bit, as he had offered me the challenge. I then, by means of "double hitches,” fastened each ankle to the corresponding leg of the chair, then tied both legs together, finishing off the rope with an attachment to the back rail of the chair. I then tied up his body, twisting the rope round and round, and fastening wherever I could get a chance. The performer was now, indeed, bound hand and foot, and could hardly move in any direction whatever. A large linen extinguisher was then placed over him, tied as he was, and I and the other spectators stood round at a little distance to see that no collusion took place. In five minutes and a-half the performer gave the signal, the extinguisher was removed, and there sat the young man free and unbound, with the ropes at his feet. I had tied him with seven pieces of rope (the usual number is four), and the seven pieces rope lay at his feet, in no way injured or cut, except at the places where I had cut them off the main piece, and I had taken the precaution to mark my own cuts, so as to know them again. I have not the slightest idea how the performer managed to loose himself; I fancy that he must use actual physical strength in so doing, as he seemed exhausted and in a profuse perspiration. Perhaps some of the readers of the Field, who have seen trick in India, where, I believe, it is frequently performed, may be able to throw some light on the matter. I understand that the performer of this Indian rope feat is now engaged at Cremorne, and that he challenges all comers to tie him so tight in the chair that he cannot unloose himself. Herr Tolmaque, the performer of this extraordinary feat, is engaged to appear at the Theatre Royal, in this town [Newcastle], during the ensuing Race-week; and the following artistes, from the principal London theatres, have also been engaged for the same period: Clara Morgan, Barbara Morgan, and Annie Cushue (danseuses); and M. Milano, (dancer.)”

Tolmaque did perform successfully for a week in June at the Theatre Royal, Newcastle, where one of his challengers proposed tying a noose around his neck (to which the performer strongly objected) and bound him with such ferocity that his arm was damaged, the chair broke, and it took seven minutes to escape. Reading between the lines, Tolmaque seems to have been learning on the job, discovering that he needed to set some limits on the severity of his lashings, which threatened to do him physical harm. The same difficulty was experienced by the Davenport Brothers, who had to fight against being bound so tightly that their circulation was cut off.

Before leaving Newcastle, Tolmaque was confronted by a copyist – the first of many to come. Herr Selmo appeared at the Shakespeare Concert Hall on July 8 and duplicated the Rope Feat. It can at least be stated that Herr Selmo was never seen again.

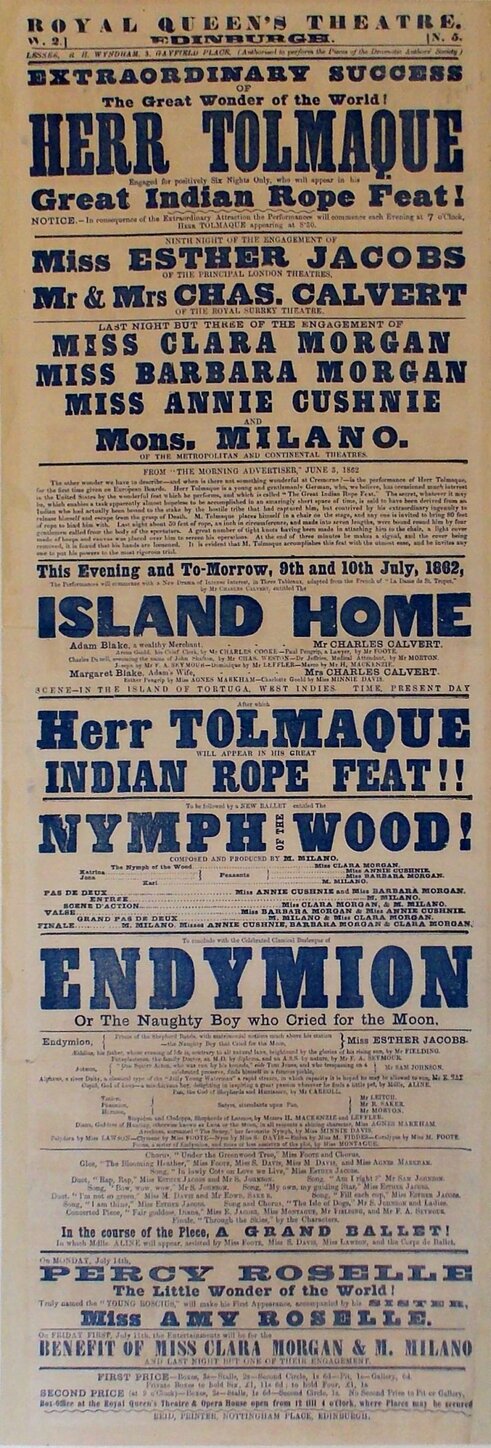

Defeat in Edinburgh

Tolmaque moved up to Edinburgh’s Queen’s Theatre for a six-night engagement and, for a few nights at least, performed his act with success. On July 12 he was tied by four men and ten minutes elapsed, during which the ‘extinguisher’ cover vibrated with the violence of his exertions. At the seventeen minute mark the cover was removed, and Herr Tolmaque was seen still bound to his chair. Addressing the audience, Tolmaque declared that he had been savagely and remorselessly tied, but that he had successfully performed his feat before, and would continue to do so; then he retired in a state of exhaustion. Since he had been performing for less than two months, Tolmaque was plainly not experienced in the ways of dealing with his volunteers, and when he was throwing out a clear challenge, was unlikely to receive much in the way of sympathetic treatment.

Tolmaque moved up to Edinburgh’s Queen’s Theatre for a six-night engagement and, for a few nights at least, performed his act with success. On July 12 he was tied by four men and ten minutes elapsed, during which the ‘extinguisher’ cover vibrated with the violence of his exertions. At the seventeen minute mark the cover was removed, and Herr Tolmaque was seen still bound to his chair. Addressing the audience, Tolmaque declared that he had been savagely and remorselessly tied, but that he had successfully performed his feat before, and would continue to do so; then he retired in a state of exhaustion. Since he had been performing for less than two months, Tolmaque was plainly not experienced in the ways of dealing with his volunteers, and when he was throwing out a clear challenge, was unlikely to receive much in the way of sympathetic treatment.Writing to the ‘Scotsman’, he said, “I always stipulate that the parties performing the operation of binding me shall not stop the circulation of my blood, and I think every reasonable man will admit it is quite possible to bind a party safely to the chair … without compressing the blood-vessels of the extremities or half killing him, as was done last night, and in spite of my frequent remonstrances. I was used more like a wild beast than an ordinary being made of flesh and blood … I hereby challenge the same parties to put my powers to the utmost test, only stipulating that a committee of medical gentlemen shall be appointed to guard against a repetition of the unnecessary violence complained of ...”. Tolmaque was a no-show the following evening, due, he said, to the injuries he had received. However, he returned on July 18 and was confronted with eight or nine men who proceeded to tie him, this time unsuccessfully, since after six minutes the escape artist sprang unfettered from his enclosure and retired ‘amid loud applause.’ A few days later, after a number of successful escapes at the Theatre Royal, Glasgow (still made up as a pseudo-Indian), Tolmaque lost his temper after being tied so tightly that he said his wrist-bone was injured, requiring the ropes to be cut off. The audience was unhappy with his complaints and Tolmaque thereupon refused to perform. Said the Glasgow Weekly Mail, “as Herr Tolmaque’s power, like the inimitable Sam Weller’s vision, is limited, he must risk such disagreeable scenes when meeting those who treat him, ignorantly perhaps, with unnecessary and painful severity.”

Broadside Detail from Royal Queen’s Theatre, Edinburgh,

July 1862. Author’s collection. >>>

Shakepearean Actor

Martin moved back to Edinburgh to take a Benefit Night at the Royal Queen’s on August 1, and for this occasion he decided to take another step in his theatrical career by undertaking the role of Hamlet in a production of the third act. The Fifeshire Journal (8) viewed the attempt with some amusement: “The representation was naturally a failure, but it was an amusing and ludicrous one; and the tragedy assumed the character of a burlesque destitute of joke and humour. Tolmaque’s Hamlet is decidedly not Fechterian, and the hemp suits him better than the buskin. By the way, why is the trick called an Indian feat, Herr Tolmaque? Judging from the facile way in which you extricate yourself from bondage, I should say the trick is not so much connected with India as with your rope.”The ‘Era’ was kinder: “With practice this gentleman might make a good third-rate Actor; but, being by nature prevented from displaying much elecutionary grace, it is certain he can never succeed in the higher walks of the Drama. We mention this as our candid opinion from the fact of Herr Tolmaque having stated his wish to adopt the Stage as a Profession and become not only a rope, but a Dramatic artiste.”

The awkwardness of Martin’s early entry into the drama is no different from his debut as an escape artist. He was learning by ‘doing’ and all his inexperience and clumsiness was played out in full view of the audience. He does make claim to having previously performed as an amateur, but no evidence of this has been found. In time, despite his disastrous appearance as Othello, as detailed in Chapter XXIII, he would become a passable actor and appear frequently on the stage; his love of Shakespeare is apparent in all of his writings.

Tolmaque accurately relates his next round of travels. He went across to Dublin and performed with success at the Rotundo Gardens, rapidly becoming more experienced and skilled at presentation. His rope feat was sensational enough to encourage a batch of copyist performers, one even adopting his name; and in ‘The Era’ of August 31 he posted a Cautionary Notice: “Herr Tolmaque considers that he is not so likely to be injured by the successful performance of his feat … however with it to be understood … he regards the more numerous the numbers who profess to accomplish it, the greater will be his own reputation for actually doing it …”

After appearing for a week at the Prince of Wales Theatre, Belfast, Herr Tolmaque returned to England where he performed at the Queen’s Theatre, Hull. Another copyist, R. Mace, was meantime performing his rope feat at Sheffield. The year was seen out with an appearance at Holder’s Grand Concert Hall in Birmingham, of which the ‘Daily Gazette’ (9) wrote, “… he is unrivalled, and perfectly original. It is a problem, a puzzle which mystifies the more one attempts to discover the secret.”

1863 – Foreign Travels

Herr Tolmaque drops from sight for several months in early 1863. The only reference that can be located comes from a rival, Mr. Edmond (or Edmund) Redmond who, in January, was at Dundee at the Bell Street Hall, replicating the Rope Feat in exact detail. Redmond, it can be acknowledged, would go on to have a long career as a magician, escape performer, and anti-Davenport campaigner. Redmond was still performing as a magician as late as 1898; in the April 1907 Conjurers' Monthly Magazine, Houdini wrote that “Dr. Redmond, who is I hear is still very much alive in England, made quite a reputation as a rope expert and handcuff manipulator in 1872-3 and I have several interesting bills of his performances.”

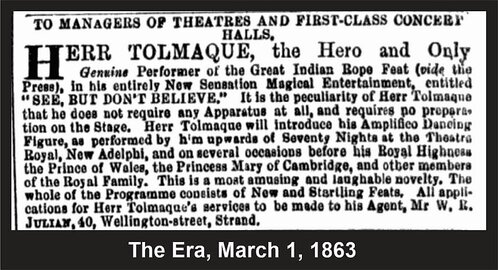

When he re-surfaces in March, Tolmaque has transformed into a magician. Documented in his ‘Struggles’ (Chapters V and VI) he had been captivated by the performance of the magician Frikell (the elder performer, Wiljalba Frikell and not his son, Adalbert). Frikell was an exponent of sleight-of-hand and minimal apparatus, and Tolmaque determined to become a magician of the same style. His advertisement in The Era on March 1 makes the claim that he had performed “upwards of seventy nights at the Theatre Royal, New Adelphi, and on several occasions before his Royal Highness the Prince of Wales, the Princess Mary of Cambridge, and other members of the Royal Family.” Of these claims all that can be said is that no supporting evidence can be found, and his later memoirs suggest rather that he was performing wherever he could, and once again learning on the job.

It seems, though, that his main theatrical appearances were with a short interlude in which he appeared as ‘the Amplifico Dancing figure’. Quite what this act was is not clear, though once Tolmaque referred to his ‘amplified dancing figure’ which he claimed to have invented, and another report (11) said “Herr Tolmaque also well merited the praise bestowed upon his performance as an amplifico dancing figure.” so it might be suspected that it was not a separate marionette or jointed cardboard dancing model, but perhaps something similar to the novelty act in which the performer pushed his head and hands through a cloth screen, with a miniature doll body at the front, giving the impression of a tiny human being who could dance and sing. (10) At Hull the act was noted as “a character quite original, but must be seen…”

Either way, he had a long run with this act at the Queen’s Theatre, Hull, in March and the Theatre Royal, Birmingham, during May, and it was only after he had finished that the Birmingham Journal (May 23) remarked, “The Amplifico Figure of Herr Tolmaque which originally formed part of the entertainment, clever as it certainly is, we cannot but regard as a performance beneath the dignity of such a stage as that of the Theatre Royal, and we are glad to find that it is withdrawn from the bills.”

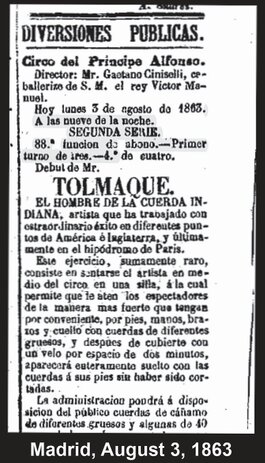

In June 1863, Tolmaque returned to his Rope Feat and accepted a booking from Mons. Arnaut of the Hippodrome, Paris. He had a successful run in Paris before travelling to Madrid, Spain, at the end of July, and here he met with a near-disaster at the Circo del Principe Alfonso that caused him to rapidly leave the city. His version of the tale is told in Chapter XII of ‘The Struggles of Life’, but in short he had arrived in Madrid to over-inflated claims that he would escape within two minutes; and then after having been severely tied, it took ten minutes to free himself. The Spanish press reported that he had cut his ropes, whereas Tolmaque claims to have broken them by his exertion; either way the excitable audience was in no mood to listen to explanations, the press said “They will take the author of such a farce to prison”, and Tolmaque saw the wisdom of moving on. He returned to Paris briefly for a benefit performance at the end of August, and then returned to England.

By October, Martin was back at Royal Cremorne Gardens, at the Marionette Theatre, but this time performing tricks and illusions “which combined rapidity with novelty” and with a Sack escape and the Rope Feat as an additional attraction.

He then drops from sight for most of 1864, re-emerging only as the Davenport Brothers began their public performances in England. Chapters XVII and XX of ‘Struggles’ indicate that Tolmaque had been severely ill in hospital at Birmingham, though it is unclear whether this was the period in question. Another likely cause is that he was entertaining in private homes, or in small venues hired by himself, which would not have been noted by any newspapers. Chapters XIII and XIV of ‘The Struggles of Life’ detail his arrangements for these evening parties. It was not in Tolmaque’s nature to confine himself to the theatre or the music hall, and his memoirs refer often to the way in which he would traipse around the country, sometimes performing for notable families, other times scraping a living out of school performances. Unfortunately, ‘Struggles’ is very light on dates and chronology.

We do know, however, that for some time he used the proprietor of The Magic Emporium (at 95 Regent Street), Mr. Henry Novra, as an agent, and that by 1865 he had also taken on Mr. William Henry Cremer junior of Regent Street, as agent. Cremer’s principal business, a large concern commenced by his father, was as a toy and game importer. He was also a manufacturer of mechanical conjuring apparatus, and he served as a manager or agent for London conjurors and ventriloquists. Cremer’s most notable association with magic was his series of ‘The Secret Out’ books (12) which were published from the early 1870s mostly under his name as Editor; it is likely that he was not the author.

Cremer advertised in the Morning Post - “Herr Tolmaque and Evening Parties. – Mr. Cremer, Jun., begs respectfully to announce that Herr Tolmaque is engaged by him to give seances at evening parties of his very successful experiment in extra-Natural Philosophy and Prestidigitation, including the Davenport Manifestations – Cremer, jun., 210, Regent-Street.”

References for Chapter One

(0) The Treatment of the Insane, No.1 by Tolmaque 1885

(1) For instance, Australian magic historian Will Alma.

(2) His register of death, however, states his denomination to be Church of England, and perhaps in Australia he would have been more likely to attend a Church of England.

(4) Saunders’s News-Letter, August 15, 1862

(5) Report of performance at the Queen’s Theatre, Dundee, July 9 1862

(6) Buckland’s original article was widely republished during June 1862, and Buckland rewrote the article for his 1868 book ‘Curiosities of Natural History – Third Series’ in reference to Tolmaque’s attacks on the Davenport Brothers.

(7) Glasgow Weekly Mail July 26, 1862

(8) Fifeshire Journal August 7, 1862

(9) Birmingham Daily Gazette November 25, 1862

(10) A complete act of ‘Living Marionettes’ is described in ‘Introducing Bill’s Magic’ by William G. Stickland, Supreme Magic Company.

(11) Hull Daily News, March 28, 1863 – Queen’s Theatre

(12) The ‘Secret Out’ books included magician’s titles including ‘Magic No Mystery’, ‘The Magician’s Own Book’, ‘Hanky Panky’, and ‘The Secret Out’ under Cremer’s editorship, as well as more general books ‘The Art of Amusing’ and ‘The Merry Circle’ credited to Frank and Clara Bellew.

(13) Home News for India, China and the Colonies, November 18, 1864