The Eloquence of Herr Martin Tolmaque

Chapter Four - Arrival in Australia - 1875

The season over, I received an offer to proceed to these colonies, which I accepted at once.

– Tolmaque, ‘The Struggles of Life’ Chapter XXXIII

– Tolmaque, ‘The Struggles of Life’ Chapter XXXIII

But when I beheld the vast and interminable bush, and contrasted its never-changing aspect with the country at home, a peculiar feeling of loneliness came over me, and for the first time in my life I became homesick. I experienced this sensation for a considerable time, and only lately have begun to feel myself more reconciled and less like a stranger in a strange land. I suppose all immigrants have felt this, more or less. – Tolmaque, ‘The Struggles of Life’ Chapter XXXIV

There was plenty of precedent for a professional magician to make the long sea journey to the Australian colonies, whether from the United States or Britain. Robert Heller arrived with his show and his assistant, Haidee, in 1869 and spent well over a year touring with great success. The Fakir of Oolu, Alfred Silvester, brought his entire family with him in December 1874, six months ahead of Tolmaque. He left a legacy of five generations of magicians and theatrical performers, and never returned to Britain. The Wizard Jacobs and John Henry Anderson had both toured in Australia over extended periods.

In all these instances, however, the wizards had arrived by arrangement with an Australian entrepreneur; Anderson, Jacobs and Heller were all represented by theatrical giant, George Coppin, and Silvester was (at least initially) under the direction of Minstrel Troupe agent, John Craigin Rainer.

Although Martin Tolmaque makes the brief statement that “I received an offer”, there is nothing to support this claim. On arrival in Melbourne the manager at the Princess’s Theatre was Mr. Boyle Robertson Patey, an ex-convict whose original name was John Patey, and who also went by the business title of Henry B. Wilton. Although Patey had an association with several magicians upon their arrival in Australia, there is no indication that he ever imported a performer from overseas. Tolmaque’s advertising makes no other reference to being under the direction of anyone but himself, and no indication that he had any planned-out tour in mind.

Why would a performer, supposedly at the height of his career in Britain, choose to up stakes and sail across the world? We can only suggest that, because he had been working recently with Alfred Silvester, the two may have discussed Silvester’s impending travel. With his usual restive and impulsive nature, Tolmaque may have decided to take his chances and follow the ‘Fakir’ to this country. Perhaps he intended to return home after a while; but Australia became his home, his prison, and his cemetery.

The ship on which he travelled from Plymouth was the St. Osyth, a steamer new to the Britain-Australia route, having made her first voyage in October 1874, returning home in February 1875. A trip under sail would previously have taken three months, but the St. Osyth reduced Martin’s voyage to just forty-five days. It was not uneventful – after departing Plymouth on May 12, and just after crossing the equator, passengers were awoken at 4 o’clock to learn that a fire was raging in the coal bunk. A massive effort from passengers and crew managed to bring the fire under control after eight hours, and the vessel arrived safely at Melbourne, Victoria, on the morning of June 27, 1875. Captain R. McNabb was given a testimonial (1) from his passengers, amongst whom was listed a “M. B. Solmaque”.

The Princess’s Theatre (now the Princess) began its life in 1854 as Astley’s equestrian amphitheatre. It was remodelled as the Princess in 1857 but, by the time of Tolmaque’s arrival, it seems to have fallen into a slump until 1886 when it was completely redesigned, to become what is now the jewel in Melbourne’s theatrical crown. The theatre was located in Spring Street at the top end of central Melbourne, and seems to have been regarded as inconveniently far to travel. The Fakir of Oolu, Alfred Silvester, had already run for a season of 100 nights at the more centrally-located St. George’s Hall in Bourke Street.

In 1875, the Princess’s was scarcely in use; save for some public meetings, and an Asiatic Circus troupe in January (a disastrous season which resulted in theatre manager Patey being charged in court with attempted fraud), it was advertised ‘to let’ by Patey for months. Herr Tolmaque was the first, and only, person to hire the Princess’s between February and December. Possibly he was unable to find a venue closer to centre of town (his first advertisements did not specify a venue), which indicates that he probably did not have a representative in Australia looking after his interests.

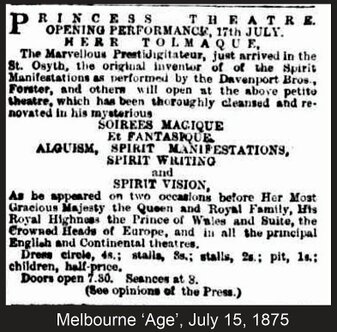

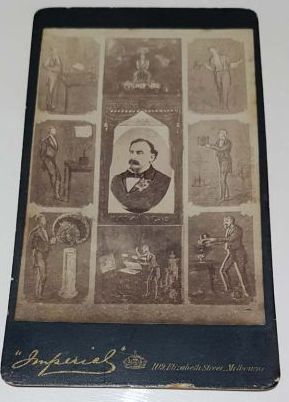

Either way, Tolmaque launched into a newspaper advertising campaign in preparation for opening on July 17, one of his promotions taking up almost the entire length of the page. (2) He set out his credentials with the names of the high-placed personages before whom he had performed, and emphasising his Spirit Manifestations of the Davenports and Foster, and a list of his wonders couched in terms which gave away little. There was to be a great distribution of confectionery for the ladies, toys for the babies, and bouquets for the gentlemen. ‘Algorism’, his great new attraction, is not clearly described anywhere, and we must assume that it was some feat of lighting mental calculation.

Said the Argus, “A private introductory performance was given at the Princess's Theatre yesterday evening, by Herr Tolmaque, who commences his soirées magiques at that theatre this evening. Herr Tolmaque, who arrived in the colony by the St. Osyth, may claim a high rank amongst the professors of natural magic. He has an easy and polished address, which soon enables him to be on good terms with his audience, and he performs his feats of sleight of hand with a dexterity which betokens long practice. The tricks he exhibited last night have been seen before here but he possesses the merit of dispensing with merely mechanical means and produces the illusion by quickness of hand only. He claims to be the original inventor of the spirit manifestation, as performed by the Davenport Brothers, Foster, and others, who attributed their performances to spirit agency, and an additional attraction is added to his entertainment by his exposure of the deceit. He shows that similar results can be produced without any appeal to supernatural causes. Last evening he performed Foster’s trick of reading the writing on papers concealed from him, and producing the blood writing on the arm. The method followed was very similar to that of Foster. Several gentlemen among the audience wrote names on slips of paper, folded them, and placed them in an envelope, which was sealed. Two gentlemen then went on the platform, and the envelope being opened, one of them chose a slip. The conjuror was at the opposite end of the stage, and he succeeded in giving correctly several of the names written, and also the name used to distinguish the slip. This name was Napoleon, and upon Herr Tolmaque baring his arm the word was seen written thereon in red characters. The performance was certainly as extraordinary as those by which Foster gained so many believers.”

The ‘Age’ said of the preview performance, “The leading characteristic of Herr Tolmaque is his extremely gentlemanly deportment. He talks with a grace that is heightened by just a suspicion of foreign accent, and delivers his anecdotes and jokes with such well-chosen language that one can hardly help imagining that he would make his mark by joining the growing ranks of the lecturing brotherhood.”

Reviewing his first evening, the papers referred to the house being ‘fairly patronised’ or ‘a good house’. The ‘Age’ praised the performance though “a little shortening of the professor’s remarks would probably be acceptable to the audience.” The Herald (July 19) was complimentary, noting that he succeeded to admiration in making ‘the eyes the fools of th’other senses.’ … the tricks, many of them of a novel character, were not only astonishing; they were elegant and amusing. The lengthy review spent the greater portion commenting on Tolmaque’s message-reading trick, and the challenge he faced, successfully, from a sceptical audience member.

Despite this, the Argus reported that the July 20 performance was only moderately attended. The Weekly Times said, “He read the pellets and did the blood-writing just as well as Foster, but he essayed too many deceptions that had already been done in Melbourne. He promises to produce on next Saturday night a very clever female medium, who will read letters without seeing them, and work other wonders which will doubtless prove attractive.” This supposed novelty was scarcely a draw, since the great Robert Heller and his talented partner, Haidee, had taken the country by storm during 1870 with their unfathomable Second Sight routine. By July 30 Martin closed his season, which the Weekly Times again said “gave too much of what was old, and too little of what is new. He next proceeds to Sydney, and on his return will re-appear in some building nearer to the heart of the city.”

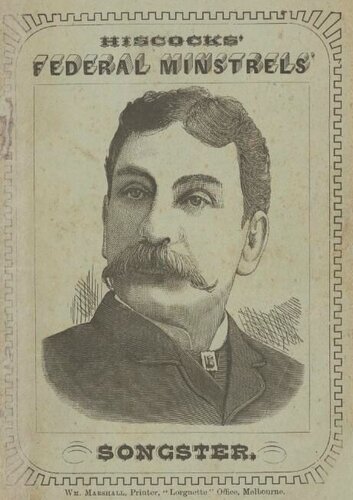

In the event, Tolmaque did not go to Sydney, but was fortunate to fall in with (3) Mr Frederick Elijah Hiscocks, an entrepreneur with an extensive history of theatre, circus and Minstrel show management, including the influential Federal Minstrels. An arrangement was made to appear during August in Geelong and Ballarat, two of the larger regional towns, and his prospects picked up immediately. Hiscocks was quite prepared to spruik his client, and Tolmaque was advertised as “The greatest living conjuror! …. Engaged at an enormous expense, the world-renowned artist who has lately created such intense excitement in Melbourne…” Unfortunately his short Geelong season was met with a not very numerous audience, though the Geelong Advertiser said, “… is an excellent linguist, has a polite and pleasing address, and … keeps his audience in excellent humour by his ready wit and choice bon mots … should he revisit this town, he will meet with the encouragement to which he is legitimately entitled.”

Attendance was a little better at Ballarat, and the Ballarat Star gave him an excellent review (4) which described some of his conjuring feats although, as always, his Blood Writing and spiritualistic routines were the highlights:

“This professor of magic made his first appearance on Saturday night, at the Mechanics’ Institute, Mr Jenkins acting as his pianist. Tolmaque is, in the elegant language of fast young ladies, ‘a perfect cure.’ He beats all who have ever preceded him here in the reduction of the art to its simplest exterior. All the elaborate show of apparatus which Anderson and Jacobs used to astonish the natives with is absent from Tolmaque’s stage. He is severer in his simplicity than Heller or the Fakir. No boxes, vases, electric drums, and so forth, but just his own swift hands and eyes, and the materials with which he does his marvellous conjurations. He is, too, a practised elocutionist, with just a dash of Cockney in his speech, and is at once outspoken and polite. Absolutely alone on the stage, no visible ‘Sprightly’ to assist him, he uses the audience for the necessary visible help he requires in his feats, and whatever aids he may have behind the scenes he is never seen to recur to them, and so the illusions are thus more absolute. Nothing is so attractive as the old-fashioned sleight of hand work when it is perfectly done, and it is in this that Tolmaque excels. His card and money tricks were swifter and cleaner in their doing than anything we have had here. How he made a ‘belltopper’ disappear and be safe whilst it seemed to be visible and smashed into hopeless ruin puzzles us still. His gun and bullet trick (6) is like no other feat before performed here. He uses an ordinary gun, borrowed in Ballarat he says, anybody in the audience loads it, marks and puts in the real lead bullet, fires the gun at the conjuror’s hand, and the bullet appears between his forefinger and thumb. There is another capital trick; He lets a gentleman select a card from a pack, tears it in four pieces, gives the selector one piece and the others to a lady. He then goes on the stage, takes an ordinary looking wine bottle, pours out a glass of wine for the Ballarat Arab whom he had got from out of the audience on to the stage, then turns up the bottle and pours over the boy's head and into his emptied glass, what looks like sago or flour. He then shows the bottle round, amongst the crowd that they may see it is an ordinary wine bottle, and then gives his wand to whoever will first take it to smash the bottle with. This done the card selected by the gentleman before referred to is found in the bottle, the fragment retained by the selector fitting exactly to the card in the bottle. But all this sort of thing is beaten in the second half of the performance, in which Tolmaque exposes the Foster ‘Séance’ business. This must be seen to be understood, that is to be understood as a quite non-understandable mystery. It is different from the Fakir’s method, and, to our fancy, much more perfect and impenetrable. Names are written by the audience on bits of paper, which are folded tightly up, into tiny morsels. These are gathered in a hat by one of the audience, who goes on the stage, with the hat on his knees as he sits fronting the audience; Tolmaque takes out a pellet; gives it to anybody to open while he, in another part of the hall, reads out the name written on it. Everybody was mystified at that, but more. Mr. Pawsey had opened one pellet, and Tolmaque, having read the name as before, asked Mr. Pawsey to touch his (Tolmaque’s) arm with it. This done, Tolmaque turned up his sleeve and bared his arm, on which was very plainly and redly written, the word in the pellet. Thus the pellets were nearly all read, all quickly, and all before the audience. But one gentleman cried out that his pellet had not been read, and he was invited to go on the stage and have a seance of his own. He went and sat at a table, and while Tolmaque walked about the stage in front of him, wrote a name, privately, and rolled it into a pellet, placed it on the table, before his own and other people’s eyes. Tolmaque sat down, had a little chat, placed the pellet on the stage in front in view of the audience, had another little chat; went to another table for a second, then took up the pellet and gave it to a gentleman in the audience to open, returning to the stage he read out the name accurately. The whole thing was a perfectly impenetrable illusion, and Tolmaque thus demonstrated what he said he would demonstrate, the possible trickery and delusions of people who, like Foster, profess to be aided by spirits in discovering what is seemingly hidden from ordinary vision. The magician appears every night this week.”

The Ballarat season continued until August 30, during which Martin conducted a Spelling Bee competition, all the rage at that time. While he had been there, a Mr J. G. Westen was performing in competition at the Academy of Music. Westen, a moderately successful magician during the 1870s-80s, also featured a troupe of performing dogs, automata, ventriloquism and escapology; but the ‘Star’ dismissed him with the crushing comment, “an inferior artist.”

J. G. Westen

Return to Melbourne

Still under the direction of Mr. Hiscocks, Martin was able to return to Melbourne, performing in a more suitable format. The Apollo Hall in Bourke Street, recently renovated, held 1,000 and was slightly more central to Melbourne’s nightlife, if only by a couple of city blocks. Tolmaque was performing in conjunction with vocalist Miss Isabella Carandini (who was Mrs. George Cottrell), and the character impersonations of local favourite, Mr. Cottrell. They opened on September 18 to a large and fashionable audience, the response was favourable, and the Herald said “Dispensing with everything in the shape of apparatus, or confederacy, his conjuring power lies entirely in his wonderful quickness of sleight-of-hand. He performs his tricks under your very nose, and yet deceives you.” By the 22nd it was reported that audience numbers were nightly increasing, and that “Herr Tolmaque has a happy facility of putting himself on good terms with his audience, and he keeps them so thoroughly interested in what he is doing, that if even his tricks were less deftly performed they would be worth seeing.”

The season was reported as having done ‘tolerably fair business’ but it was announced to close at the end of September, and Tolmaque announced that he would re-open at the Apollo on October 4, with several talented artists. He also advertised for a manager who “must be honest and reliable”, but he appeared on October 5 as ‘sole manager’ with Professor Abder, ‘The Celebrated American Lyric Phenomenon’; he was an imitator of birds, beasts and the piccolo. The venture did not last, as by October 9 Mr. Abder was performing elsewhere, and nothing more is seen of Martin until he arrived in Wangaratta for two evenings on October 20 and 21, now managed by a Mr. J. T. Whitty, and with later appearances scheduled for the northern Victorian towns of Beechworth and Albury, Milawa, Chiltern, Benala, Wahgunyah, Wagga Wagga, and back to Beechworth by November 27. At all these towns with the exception of Wagga, the audiences were good and the commentary pleasing – (5) “… a highly intellectual audience witnessed some conjuring feats deftly and elegantly executed… the gentleman possesses one great requisite, viz., a polished address, easy and gentlemanly. This was the means of placing himself and his audience en rapport, and applause, hearty and well deserved, followed each of his various sleight of hand tricks.”

Finishing off the year, Herr Tolmaque appeared at Eldorado where it was reported, “the audience fairly shouted with delight, and from beginning to end the professor succeeded in eliciting the most vociferous cheers from his patrons.” He may have been a long way from the bright lights of Melbourne, and further from the snowy Christmas of London, but at Myrtleford and Yackandandah, Martin Beaufort Tolmaque was living his best life.

New South Wales - 1876

The lesson that our magician would have taken from his first regional tour is that, unlike his British travels, Australia was not a place to be enjoying a country walk from town to town. Not only was the population of most towns far smaller than in Britain, the distances between them could be enormous; from his base in Beechworth to Wagga Wagga the trip was 173 kilometres, and even from Beechworth to Myrtleford was 28km. The journey was not along hedge-lined country roads either; the countryside could be open and scrubby, and during the summer months at the start of the year, temperatures might climb so high as to make a long walk impossible.

Some rail lines were developing, but slowly and only between major locales. Magicians without their own form of transportation would need to base themselves in a central township and travel out to smaller places, or situate themselves in the major cities, of which there were relatively few in each state.

After performances in Albury and Ballarat in January 1876, Tolmaque was reported to be in Melbourne ‘out of harness’. He advertised a few times that he was destined for New Zealand (where in fact he may have enjoyed something closer to British conditions) but he did not make the trip. Instead he set his sights on the city of Sydney and left aboard the s.s. You Yangs on February 19, to lodge in Sydney at the newly-renovated Bowden’s Club House Hotel in Hunter Street, from which he advertised himself available for public and private bookings.

After some side-trips to both the Wollongong Temperance Hall and Newcastle’s Theatre Royal in Watt Street, Martin found a comfortable venue at the School of Arts in Pitt Street. Here, from April 15, he featured amongst ‘John W. Smith’s Combination of English and Continental Artists’ including Pemberton Willard the rapid costume-change artist, John Moran the comedian and singer, Launcelot (Lance) Lenton with ethnic comedy, and Mons. De Croix, slack-wire walker. This was a company and a venue ideally suited to Tolmaque’s strengths; the theatre (or more accurately, lecture hall) was the right size to display his prop-less magic. The Evening News (April 22) reported that the entire programme was exceedingly varied and that “actors and audience are on first-rate terms with each other.” Tolmaque was “a clever conjuror; his wit is sharp, polished and of good temper, whilst his fund of small-talk proclaims him a complete master of those situations where intervals occur in performances of this class.” In other words, Tolmaque’s eloquence covered the stage-waits between tricks!

The combination show ran for several weeks with apparent success, though it ended a little sooner than hoped, in early May. Martin, however, moved a few blocks away to the Queen’s Theatre in York Street, where he joined another combination troupe from the start of June. After barely a week he was advertising his final night and Benefit performance, but he had another plan.

Chinese Giant

The Queen’s Theatre was making a feature of a Chinese Giant, whose name was most often spelled at Choukitczee (or variations including Choukicza). He was thirty years old and said to stand at 7 feet 11 inches, some seven inches taller than the better-known giant, ‘Chang’. It is likely that Tolmaque cut short his own season at the Queen’s because he had made an arrangement to go out as a lecturer for Choukitczee, and by June 16 he was back at the School of Arts as front-man for the giant. Billed as “Herr Tolmaque, wit, humorist and Prestidigitator”, he related the supposed story of Choukitczee’s involvement in the Chinese Rebel War, while the giant, attired in the robes of a Mandarin for purely glamour purposes, illustrated some of the manners and habits of Chinese society, and engaged in the usual practices of a human who was being ‘exhibited’ – shaking hands, making a speech in his own language and posing politely. Tolmaque supplemented the exhibition with his own magic performance.

From June 22 they moved up north to Maitland, then to the Victoria Theatre in Newcastle. The story related, which cannot be confirmed, was that Choukitczee met his promoter (a Mr. Paul Starick) when he was a soldier in the Imperial Army, taken prisoner after being wounded in the Chee-Foo battle of 1866, but was saved by Starick, and had since visited Shanghai and Hong Kong. Tolmaque was ever ready to make a speech, and the Newcastle Chronicle wrote, “Herr Tolmaque’s introductory narrative will bear shortening considerably.”

A more credible version of the tale was given in the Burrangong Argus (August 19) – “He was discovered in the north of China by the gentleman who has brought him here, and who on his saying he was too big to work, proposed to him to exhibit himself for the support of his wife and family.”

The giant moved on, guided by Mr. Starick and their agent W. H. Smith, and at the end of July they sailed for Melbourne, but without Herr Tolmaque, who is not seen again for another couple of months.

Queensland - 1876

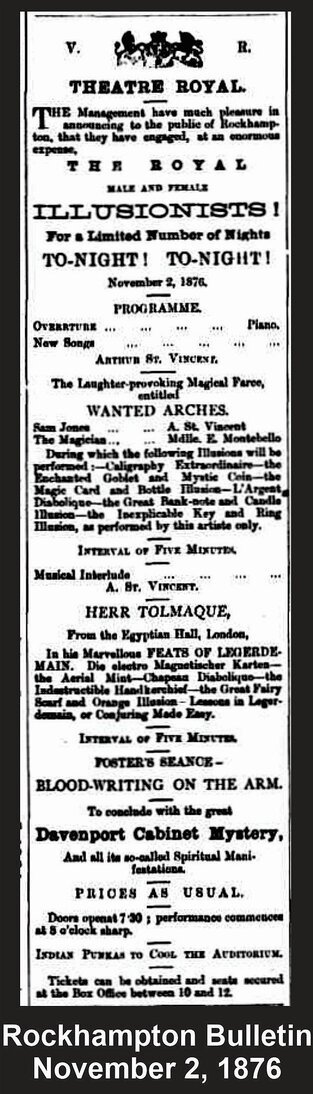

One possible reason for his absence in the press, might be that Martin was busy organising his next venture. He made a couple of brief appearances at Wollongong and Kiama, south of Sydney, where his magic was praised as “beyond anything of the kind seen in Kiama before, but the rope-tying trick, a la Davenport, is a marvel ….”On November 1, he suddenly appeared a full 1,500 kilometres north of Sydney, at Rockhampton in Queensland, having sailed there in the steamer ‘Boomerang’ (1854-1898). With him were two performers, Mr. Arthur St. Vincent and his wife, Madamoiselle Eugenie Montebello.

The duo were Britishers known as general versatile variety performers – they had, earlier in the year, featured at the Apollo Hall with an assortment of songs, comic routines, the skilled Japanese juggler named Awata Katsunoshin, and a send-up of the current magical star of the day, Alfred Silvester the Fakir of Oolu. Montebello (born in Italy) was also known for her male impersonation.

Mdle. Montebello presented a magic act with great success:- (7) “… the great feature of the night, that which will make this entertainment take, was the act called The Fakir To Do You. This consisted of magic, the Fakir being impersonated by Mdle. Montebello, and Sprightly by Mr St. Vincent. Mdle. Montebello’s magic is quite as good as any we have ever seen. The ring trick was so deftly managed that the audience were quite mystified. A large number of other tricks were well done. But Mdle. Montebello’s style is greatly in her favour. She keeps the audience on a simmer of laughter all the while, and her insouciance and humour help her on wonderfully. Mr St. Vincent manages Sprightly very well.”

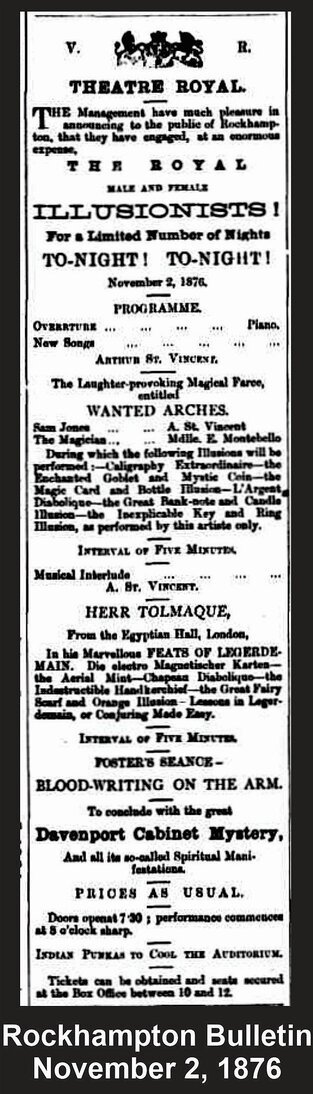

The new ‘troupe’, or trio, opened as ‘The Royal Male and Female Illusionists’ at the Rockhampton Theatre Royal, on November 2. The programme featured songs from Mr. St. Vincent, followed by a farce titled ‘Wanted Arches’ involving St. Vincent and Montebello, and during which they presented these tricks:

Telegraphy Extraordinaire – the Enchanted Goblet and Mystic Coin – the Magic Card and Bottle Illusion – L’Argent Diabolique – the Great Bank-note and Candle illusion – the Inexplicable Key and Ring illusion.

After a short interval, and more songs, Herr Tolmaque gave his act:

Die electro Mangetischer Karten – the Aerial Mint – Chapeau Diabolique – the Indestructible Handkerchief – the Great Fairy Scarf and Orange illusions – Lessons in Legerdemain, or Conjuring Made Easy, and Foster’s séance entitled Blood Writing on the Arm.

Another short interval, and Tolmaque concluded the show with his Davenport Cabinet Mystery.

Following their first appearance, the Rockhampton Bulletin was impressed (“Mdle. Montebello does her tricks neatly … Herr Tolmaque regularly thrilled the audience with astonishment …”) but again there were the words which heralded problems – “it is but fair to say that they deserved a larger share of public patronage than they received.”

The third performance by the Illusionists was marred by initial difficulties in finding a volunteer to tie Tolmaque, and when someone was found, he spent over fifteen minutes on the job, to the impatience of the audience and the exhaustion of the performer in the Queensland heat. When the volunteer asked for even more rope, Tolmaque called for fair play but the rowdier gallery audience voiced their feelings against him; the magician insisted on being untied, and uttered some pithy words to his audience. The Bulletin hoped that “when he re-appears he will be treated as a gentleman, and in a manner worthy of twenty years standing as a professional.” A small flurry of words and challenges ensued in the press over the next few days, all coming to nothing although the magician had the final say by offering to enter his cabinet with a 12-yard length of rope, appearing within one minute in a fully tied state which no person in the audience could untie in less than fifteen minutes, with a £20 reward at stake.

The Royal Male and Female Illusionists continued with performances at Maryborough and Gympie, receiving favourable commentary until the end of November.

Montebello and St. Vincent then split from the trio, and went to Charters Towers where they appeared at Christmas as ‘St. Vincent’s London Comic Concert Company’, featuring amongst their magic a convenient addition of ‘spiritual manifestations’ to their repertoire. They also settled to live at Charters Towers. (8)

Herr Tolmaque’s Christmas season of magic, at Brisbane’s Queensland Theatre as part of Exhibition week, was a solo performance. The theatre was “crowded to excess, numbers of persons being unable to get seats” and Tolmaque was said to have “ a very attractive style, and the manner in which he both introduced and performed the various feats was greatly applauded.” (9)

References for Chapter Four

(1) The Argus (Melbourne) June 28, 1875

(2) The Argus, July 17, 1875 page 12

(3) Frederick E. Hiscocks (1842 – 18 July 1901) of Hiscocks, Hayman & Co, manager of St. George’s Hall, and of the Elsie Lander Dramatic Company, the Federal Minstrels, the Hicks-Sawyer Minstrels, The Mammoth Minstrels, The Little Midgets, also associated with Al Hayman, J. Allison, George Rignold, N. Hegarty and J. Wilson. Hiscocks also ran an Atlas publishing firm. He died relatively young having had a severe accident in 1901, and then contracting pneumonia.

(4) Ballarat Star, August 23, 1875

(5) Ovens and Murray Advertiser (Beechworth) November 4, 1875

(6) Advertising in the Albury Banner, January 8, 1876, shows that his gun trick was billed as ‘Tell’s Shot’.

(7) The Herald (Melbourne) January 4, 1876

(8) St. Vincent left his wife at Charters Towers around 1882 while he returned to England with plans to bring back a touring company. He and the company were shipwrecked on the Island of Gothenburg and lost everything; he managed to return to Australia.

(9) The Queenslander, Brisbane, December 30, 1876 p.14