The Eloquence of Herr Martin Tolmaque

Chapter Two - The Davenport Brothers

We never in public affirmed our belief in spiritualism. That we regarded as no business of the public, nor did we offer our entertainment as the result of sleight-of-hand or, on the other hand, as spiritualism. We let our friends and foes settle that as best they could between themselves but, unfortunately, we were often the victims of their disagreement. – Ira Davenport, writing to Houdini

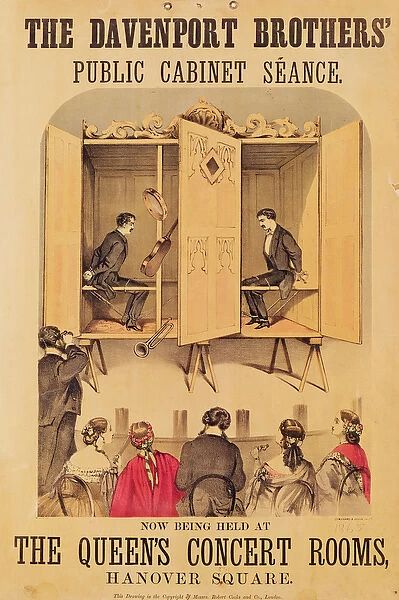

The furore which was the Davenport Brothers hit Britain in October 1864. Having spent ten years touring in their native United States, the brothers Ira Erastus and William Henry Harrison Davenport arrived to perform their highly-disputed act of implied spirit phenomena, little prepared for the chaos that would follow them.

The brothers were guided by Dr. J. B. Ferguson (a follower of spiritualism). Their Secretary/Manager was Mr Henry David Palmer, an operatic agent and manager of Niblo’s Garden theatre in New York, who arranged for the brothers’ first seances in Britain to take place at the private residence of playwright Dion Boucicault. William Marion Fay was from the brothers’ home town of Buffalo. He was the standby performer when William Davenport was ill from tuberculosis, took part in the second ‘dark’ section of the show, and would go on to work with magicians Harry Kellar and Alfred Silvester. There were two variations of the ‘séance’. In the ‘Light Séance’ (1) the brothers were first roped by the hands and legs to seats inside a wooden cabinet, the cabinet doors were closed, and pandemonium ensued with musical instruments being played, bells rung, rappings heard and bare arms protruding through a window in the central cabinet door.

The Light Séance routine is generally described as the brothers being tied, then musical instruments commencing to play immediately the doors were closed. However, there are sources (1) which indicate that at times the brothers would open the cabinet, revealing that they were free from their ropes (by some ‘mysterious’ force beyond their comprehension), and that after the cabinet was once more closed, it would be opened to reveal them tightly bound. It seems theatrically incongruous that the brothers would blatantly demonstrate that they were able to free themselves and re-tie themselves, since their entire routine hung on the concept that they had been securely tied and were unable to move.

Although the Davenports were not strong advocates of the widespread Spiritualist movement, they were an example of the movement’s main problem – its banality and focus on spectacular but meaningless phenomena:

Newcastle Daily Chronicle, January 12, 1865 - “It is difficult to believe that any persons with a true respect for the sanctities of the grave, would connive at such an exhibition as the Davenport Brothers, even, if true, in a spirit sense. It lowers your ideas of a future life, and makes it ridiculous and undesirable. If messengers ever come to us from the Silent Land, may we not expect they will come with gentleness and speak with wisdom, revealing the wondrous experience of untold life; exciting no fear, affecting no mystery, doing no capricious, purposeless, cruel or ridiculous thing? Such visitant would minister to the moods of the mind which come to all who have known sorrow….” - Landor Praed (3)

The British public, though there were many sincere spiritualists, had no patience for the brothers’ manifestations. This was a challenge to restrain the performers, nothing more. The British tour turned into a series of confrontations, disputes and near-riots, as audience members (some of who followed the performers from town to town) tied the Davenports with the most severe methods they could devise; including a knot known as the ‘Tom Fool’s Knot’, which was ultimately their downfall, in New Zealand in 1877. At Huddersfield, Leeds, and Liverpool the Davenport performances turned into rowdy debacles.

In addition to the combative attitude of their audiences, the Davenports were nearly swamped by a wave of professional magicians eager to either expose, criticise, or jump on the publicity bandwagon of the cabinet conjurors. In Britain Herr Tolmaque was at the fore, along with John Henry Anderson (the Wizard of the North), Professor Redmond, a young John Nevil Maskelyne and George Cooke, and the Brothers Nemo all leaping into the fray, while in the following year it would be Henri Robin and Jean Eugène Robert-Houdin heading up the French opposition.

The dynamic between magicians and the Davenports is a ripe field for analysis. Undoubtedly, many magicians were genuinely offended by what they saw to be a prostitution of their art – modern magicians were avowedly tricksters and had no need to pretend any supernatural powers. There were also many eager to line their own pockets by hitching a ride on the Davenports’ fame, filling their repertoires with exposures or duplications of the brothers’ feats, and taking a share of the publicity generated by controversy and conflict.

Ultimately, the Davenport story is one of pure pragmatism on all sides, with the possible exception of the ‘true believers’ in spiritualism. Like prize-fighters trash-talking for the cameras, all the public antagonism and debate was grist to the mill. The Brothers Davenport walked away with a vast sum of money. Their opponents benefited from the publicity, but also discovered a whole new source of inspiration for their magic shows – in the decades to come, countless numbers of the least and most famous magicians would feature some form of ‘Davenport Cabinet’, rope-tying, or other pseudo-spiritual routine in their acts. John Nevil Maskelyne effectively began his career as Britain’s premier magician by opposing the brothers; Harry Kellar not only made the spirit cabinet a feature of his show, he employed William Marion Fay to work with his show after Fay had a falling-out with William Davenport. There is no question that the field of escapology took off via the sudden surge in rope-tying and escape methodology, and Harry Houdini would, much later, befriend Ira Erastus Davenport and gain his trust to such an extent that Ira is said to have taught his methods to the escape king.

Some years later, when the Davenports came to Australia in 1876, they were faced with an ‘expose’ presented by the British magician, Alfred Silvester (the ‘Fakir of Oolu’) and his son. Yet Silvester, now resident in Australia with his family, was spotted offstage:

(4) “The Brothers are to give performances at the Town Hall … Last night I strolled into the café of the Theatre Royal, and sat at a small table sipping a friendly cup of coffee, between the Davenport Brothers and the Fakir of Oolu. All the wizardry of the world seemed concentrated around that table, yet were the wizards in private life affable and civil persons enough.”

After the death, through tuberculosis, of William Henry Harrison Davenport in 1877, Silvester would tour to Java and Singapore with William Fay.

In the same fashion, then, that modern-day debunkers of pseudo-psychics struggle to make headway, because their protestations become nothing more than fodder for publicity, so the opponents of the Davenports might shout and object; but in the long term the philosophy of P.T. Barnum prevailed, everybody held firmly to their own entrenched positions, the money rolled in and the circus rolled on.

Herr Tolmaque stated his reasons for stepping up against the brothers: (5) “… the great feature of the evening was his demonstration that the ‘spiritual manifestations’ of the Brothers Davenport are a complete delusion .. he then stated that he was the original author of the trick, and should never have come forward to oppose or expose the Brothers Davenport had it not been that they mixed up ‘spiritual manifestations’ with what was really a question of manual dexterity and skill. He admitted them to be very clever in their way but these pretended agents from another life had been the cause of a good deal of moral mischief, especially in America, where many persons had gone made and were confined in lunatic asylums … The trick was no doubt a very clever one, but the agents engaged in it played not a passive but a very active part.”

John Henry Anderson was content to criticise the Davenports while remaining on his own stage. Tolmaque was rather more emphatic. In the Dublin Evening Mail, October 3, 1864 he wrote:

“… Can the Messrs. Davenport produce the second part of their séance in any place where the cabinet is not, or where there is light?” I answer no; most emphatically, no. Far be it from me to interfere with any parties in the proper exercise of their vocation, but when conjuring tricks are made the mediums of deceiving those who are predisposed to put faith in spiritualism, I consider I have an undoubted right to take the matter into serious discussion.

As certified by Dr. Frank T. Buckland, of the 2nd Life Guards (a gentleman both unimpeachable and undeniable in his statements), I have performed, alone and unaided, the principal part of Messrs. Davenport, Fay, and Co.’s entertainment, first at Cremorne, and subsequently in France, Germany, and Spain, but have always admitted the trick, and in no instance have I deceived the public by pretending to ‘extraordinary spiritual manifestations.’ Now, sir, for the benefit of all those who believe in spiritualism, I beg to state that all the wonderful experiments witnessed by your correspondent are traceable to natural laws and the science of conjuring, mixed up with no small portion of the conjuror’s never-failing friend – humbug:- I am prepared to prove what I assert, and the very parties who have witnessed these ‘extraordinary spiritual manifestations’ may test my powers in the following manner. I will permit any gentleman, or number of gentlemen, to bind me, hands and feet, in a chair, and, instead of putting out the lights, merely request one of the company to cover me with a linen extinguisher, such as described by Dr. Buckland in his letter to the ‘Field’, and in this position will ‘show hands,’ make noises on different instruments, change coats, &c. I will do all this, sir; but I will not attribute these feats to any supernatural agency. I have the honour to be, sir – Your most obedient servant, M. Tolmaque, Prestidigitateur, 3 Newcastle-Street Strand. Sept.30”

He was stretching his own abilities here. The fact that he was capable of escaping from a rope tie did not, by any means, place his act in the same league as the Davenport’s multi-faceted, skilful and entertaining seances. Tolmaque’s critics would use this fact against him, throwing out challenges that he must exactly replicate the Davenport act; although this, of course, was just another way of appearing to issue a challenge while carefully retaining plausible deniability.

The battle of words began, and the Davenport management challenged both Anderson and Tolmaque to a séance; and Tolmaque declared that he would have nothing to do with the Davenports unless they performed in the light. “I am simply actuated by a wish to oppose an ‘untruth’ of a nature so terrible”, he wrote to the Morning Post, “that the extent of the evil it produces cannot be calculated, for I know full well that a very large portion of the ‘upper ten thousand’ are more or less believers in spiritualism and out of whom a rich golden harvest may be gleaned by unscrupulous persons, a proceeding which will never be resorted to by him who has now the honour of addressing you.”

John Anderson stayed clear of a contest – “M. Tolmaque sent a challenge to the Brothers Davenport; I did not. Why do the Brothers Davenport make so singular a mistake? How is it they take no notice of what has occurred, and reply to what has not? Is it for the purpose of making my name a medium of gratuitous advertising? If so, it is a very clever dodge, but I am afraid one that won’t work with your obedient servant.”

Mr. Palmer upped his offer to £100 but only on the condition that anyone would “by legerdemain produce precisely the same phenomena as those to which the Brothers Davenport give rise, under precisely the same conditions, to the satisfaction of a majority of the gentlemen and noblemen who were present at the séance held last Friday evening at (Boucicault’s) the Hanover-square room. The party, of course, attempting, should he fail, to pay a like sum ….” A solo performer, then, however successful, would not have precisely replicated the act of two brothers.

So the bickering continued, and Professor Anderson cleverly stood back from the fracas, while at the same time presenting his daughter, Lizzie, and a ‘muscular assistant’ on his stage, where they escaped from bonds and performed a semblance of the Davenports’ musical instrument playing and throwing. The Daily News, October 29, said, “Professor Anderson has done little more than advertise [the brothers] and himself too, and we are still waiting for some one to take up Mr. Palmer’s £100 challenge.”

Tolmaque presented a somewhat rudimentary duplication of the spirit manifestations at the New Theatre, St. Martin’s Hall in early November, with the assistance of Dr. Frank Buckland, and he was no more kindly treated than usual, at one stage having to decline to be tied “like a wild beast.” He escaped his bonds in just a few minutes, but the press noted that he “failed in reversing the process.” Professor Redmond was now engaged by Astley’s Theatre and gave his rope-tying exhibitions, while Tolmaque moved over to the Hanover-Square rooms to give “a grand evening séance …. Anti-Spiritualistic Wonders” amongst his conjuring. He gave a speech in opposition to the Davenports’ entanglement in claims of spirit assistance, and was loudly cheered.

The Brothers Nemo were also jumping on the bandwagon, and mention was made of “a certain champion swordsman (6), not unknown to fame as a divider of sheep, has also issued a wild challenge in this matter, feeling able, no doubt, to cut the most complicated Gordian knot that can be put before him. We shall unquestionably be well laughed at by our irreverent grandchildren.”

Herr Martin was the most prominent of the Davenport critics at this time, and he headed for Newcastle’s Theatre Royal in December, presenting ‘The Tolmaque Wonders’ and receiving a warm reception for what the manager, Mr E. D. Davis described as “dispelling the gross imposition of spiritualism, and in order to make manifest the absurdity and profanity of the attempt of the Brothers Davenport to attribute to supernatural causes the effects which are actually produced by skilful legerdemain.” Tolmaque also performed for private audiences, and ‘Flaneur’ of the Morning Star sarcastically wrote (7), “Indeed, here is Herr Tolmaque’s only shortcoming. What he has to do he does readily and at once; he want an oily, bland, smooth-spoken stump orator, with the gift of the gab, and the knowledge when to speak and when to be silent – he want a showman in fact – and if he succeeds in getting one in any way as fitted for the post as Dr. Ferguson he may thank himself lucky.”

1865 proved to be a far hotter time for the Davenports. Until now the controversy had amounted to not much more than shouting from the battlements, but in February two men challenged the rothers at Liverpool with what was known as the ‘Tom Fool’s Knot’. John Hulley and Robert Cummings insisted that if the brothers were passive participants in their manifestations, they should have no problem with being bound by a knot from which they had no means of escaping. Ira Davenport complained that the knots were too tight, and had Dr. Ferguson cut a rope, which injured his hand. The performance descended into a riot, during which the cabinet was smashed to pieces.

Prior to this, Tolmaque was at Eastbourne where he had a verbal stoush with a Mr. Cooper who wished to promote the Davenports’ point of view, and challenged him to a test; which Tolmaque passed with considerable success, notwithstanding that Cooper protested that he had not ‘played a tune’ on the séance instruments, as the Davenports did.

By the time of the Liverpool riot, as related in Chapter XX of his memoir, Tolmaque was in London giving his seances at the Royal Alhambra Palace, when he was contacted from Liverpool and asked if he could overcome the Tom Fool’s knot. By February 24, he had been engaged to appear at the Liverpool Royal Amphitheatre to perform and then explain the Davenport Rope Tricks and mysteries of the dark séance. Herr Martin was securely bound by a local sailor, who was rather dismayed when the escape artist freed himself, played a tambourine and a bell, and showed his hands from behind the light cabinet in which he was enclosed. Tolmaque admitted that his escape had cost him a great effort, and that he had been tied in a manner to which the Davenport Brothers would not have submitted. His wrists were bleeding, and thus on the first night he was unable to perform his explanatory segment until the next evening.

From Liverpool, Tolmaque went to Birmingham (“The Liverpool Tom Fool Knot not objected to” stated his advertising) but received weak responses; not due to his own skills, but because audiences seemed disinclined to give him the robust tying that would create interest. By April Martin was returning to his performances of magic and is noted at Gravesend and Sevenoaks with a “budget of startling magical illusions to a small but by no means disappointed audience.”

The Davenport Brothers moved on to France, where they met with as hostile a response as they had seen in England. The Usk Observer (9) saw them off with an unkind poem:-

A FAREWELL TO THE DAVENPORTS

They tell me 'tis decided — you depart!

'Tis wise, 'tis well, and not at all a pain;

We had enough of your expensive art,

We were the victims, and won't be again!

Farewell, my Ferguson; and if for ever,

Why, then, so much the better — fare thee well!

Good-by, Arcadian pair of brothers — never

Shall we forget the "structure" and the bell!

Pack up your household ghosts, no longer stay;

Palmer, good-bye; and thou, sweet Fay — away!

True, you brought in the newest thing in ghosts,

The latest phantom fashions from the West;

Home is not worth a rap; and Foster's boasts,

Compared with yours, are shabby, second best,

All very fine, O Ferguson! no doubt,

But one grows tired of squeezing goblin paws;

The spectral nigger melody's played out,

And even the rope, I think, no longer draws.

Dear friends - you know that you were rather dear -

There is a world elsewhere - then stay not here!

Even at half-price your goblins charged too high

Giles Scroggins never made a rap by his;Dead Caesar met his foe at Philippi,

Nor asked a sixpence when he showed his phiz.

Banquo's red spectre made a splendid show;

And Hamlet's dismal father, though a bore,

And Mrs. Veal, as told of by Defoe,

And sweet Miss Baily, famed in song of yore -

All these were phantoms of the rarest merits,

But, unlike yours, they came as untaxed spirits.

Come back no more till you can utilise

The "unknown force" you sell so very high;

Perhaps some day you yet may win a prize

For well-trained ghosts with warrant not to shy;

Nay, and the period may perchance be near

When smart New England boasts some new machine,

Worked all by forces from the phantom sphere:

Shirts sown by armless fingers shall be seen,

And engines fifty-ghost power shall be sold,

And goblin ploughs turn up the toughest mould.

Farewell! Good fortune follow, though you leave

Our cherished childhood's ghosts not worth a button;

May you find idiots easy to deceive;

May you pursue your trade unvexed by Sutton;

May no tormenting Tolmaque dog your track,

No scoffer, and no Scoffern, spoil your meetings,

No Oxford gownsmen hurl your "structure back",

No Flaneur's laugh profane your spirit greetings.

Ira and William, Ferguson and bell,

Palmer, Fay, structure, banjo - all farewell.

References for Chapter Two

(1) The ‘Dark Séance’, often performed with William Fay, was more or less the same phenomena but without the cabinet, the performers being circled by the audience and the lights extinguished (leaving them open to exposure when a window curtain blew aside, or when students created phosphorescent chemical balls to light up the room). William Fay’s forte was in magically donning a borrowed coat, while fully tied.

Historian Henry Ridgely Evans, in several of his essays on the Davenport (including ‘Hours with the Ghosts’) states:

“In the Light Seance a cabinet, elevated from the stage by three trestles, was used. It was a simple wooden structure with three doors. In the centre door was a lozenge-shaped window covered with a curtain. Upon the sides of the cabinet hung various musical instruments, a guitar, a violin, horns, tambourines, and a big dinner bell. A committee chosen by the audience tied the mediums' hands securely behind their backs, fastened their legs together, and pinioned them to their seats in the cabinet, and to the cross rails with strong ropes. The side doors were closed first, then the center door, but no sooner was the last fastened, than the hands of one of the mediums were thrust through the window in the centre door. In a very short time, at a signal from the mediums, the doors were opened, and the Davenports stepped forth, with the ropes in their hands, every knot untied, confessedly by spirit power. The astonishment of the spectators amounted to awe. On an average it took ten minutes to pinion the Brothers; but a single minute was required for their release. Once more the mediums went into the cabinet, this time with the ropes lying in a coil at their feet. Two minutes elapsed. Hey, presto! the doors were opened, and the Davenports were pronounced by the committee to be securely lashed to their seats.”

I have been unable to locate a primary source to confirm this description, which does not match the usual process mentioned in newspapers. However, in The Sun (London) of October 6, 1864, the Davenports are seen to have been ‘mysteriously’ untied:

“The theory of the Americans is that by whatever agency they are untied, they themselves are passive agents in the matter, and that their own hands in no way contribute to their release. An ingenious test was applied a few evenings since at a séance which took place at the Queen’s Concert Rooms, Hanover-square, to prove the value of the assertion. To show that the uncording was not effected by the hands of the Americans, some flour was procured and after the process of pinioning had been accomplished to the satisfaction of all present, the fingers of the brothers were covered with the substance, and they were required to hold a quantity of it firmly in their hands, clasped and locked the one in the other. They were at the time dressed in ordinary evening costume, and it would have been impossible for them to have untied the ropes, and subsequently tied them again without being covered in flour. The result was as the Americans predicted it would be. When the doors of the cabinet were thrown open they were found with their limbs untied, and in precisely the same positions in which they had been left, but with no portion of the flour on their clothes. The doors of the cabinet were subsequently closed, and after an interval of two or three minutes were thrown open, when the brothers were found tightly pinioned hand and foot, and clutching the flour as before.”

(Harry Houdini later reported that Ira Davenport told him “they did not need to get rid of the flour in their hands as they could do all the tricks with their hands clenched using the free thumb.” – A Magician Among the Spirits, 1924)

(2) Transcription from the London Times, dated St. James’s Hall, Sept 30, 1864

(3) Landor Praed - pseudonym of George Jacob Holyoake, newspaper editor and prominent secularist.

(4) The Queenslander (Brisbane QLD) September 2, 1876, from the Melbourne correspondent.

(5) Morning Advertiser (Britain) November 18, 1864

(6) ‘Home News for India, China and the Colonies’ November 18, 1864. The swordsman mentioned is unknown, but in Australia it would have been a reference to the champion swordsman Professor George Parker, whose most famous feat was slicing through a sheep carcass with a single sword blow.

(7) From the Berwick Journal, December 20, 1864

(8) Eastbourne Gazette and County Advertiser, February 15, 1869

(9) Usk Observer, January 21, 1865