The Eloquence of Herr Martin Tolmaque

Chapter Seven - Collapse

I had a light and easy heart, a great belief in myself, and to crown all, I had an entertainment which had stood the test of public opinion for some years, and which never failed me. - Tolmaque, The Struggles of Life, Chapter IX

Some 12 months ago I conceived the idea of ‘doing the vagabond’ on an entirely original and certainly new principle. Bold and rash as the conception may appear, and dearly as I have paid for my determination, I nevertheless feel there is more than ordinary satisfaction in being able to say, like the Roman of old, "alone I did it!" - Tolmaque, The Treatment of the Insane, No.1

To all appearances, Martin Tolmaque was proceeding in his usual fashion, jumping from place to place and giving his performances and readings with varying degrees of success. In March 1884 he arrived at Launceston in the Tasmanian north-east. Amongst the usual puff pieces heralding his arrival, the ‘Tasmanian’ of March 1 commented that “Professor Tolmaque has been residing in Tasmania for two or three months past for the benefit of his health.” Another passing reference would be made in the following month, (1) “…. Ever since he was a patient in Hospital [previous to March 23]”.

He gave an entertainment in the Mechanics’ Institute and though the attendance was once again somewhat small, he gave his usual programme of magic, spirit phenomena and phrenological readings, with another show promised for the following evening. He was meantime available for private consultation at the Coffee House. There were further performances, for the City School and at Beaconsfield hall, with a show at the Launceston Mechanics’ Institute advertised for March 22. There was no indication of any problem, the shows being well received.

Just days later, on March 25, it was reported that Tolmaque had been detained by the police on the grounds of being of ‘unsound mind’; the next day, Launceston’s Daily Telegraph reported the woeful tale:

“A Pitiful Sight.— Yesterday morning, at the Police Court, Martin Beaufort Tolmaque, better known as Professor Tolmaque, was remanded for three days on the charge of being of unsound mind. The professor, who was in a state of suppressed excitement, informed the Bench that he was being poisoned, throwing as evidence of the charge some remarkably soiled crumbs, before the Police Magistrate. He stated he was very ill, and might die in three days, requesting that he might have medical advice. Mr Murray informed him that he had no power to do more than simply remand him. The defendant was removed after he had given utterance to various unintelligible charges. It would appear that for some days past the professor has shown unmistakable symptoms of aberration of intellect. Taking his stand opposite Mr Sutton's Coffee Palace on Friday, the Professor tried to use his mesmeric powers on the solid building, and by sundry energetic actions of the hands endeavored to mesmerise the hotel with its numerous occupants. Finding his endeavors futile he turned his attention to the Police for the purpose of mesmerising the whole force generally, but Sub-Inspector Sullivan in particular. He next announced he was His Satanic Majesty, finally becoming so obstreperous that it was found necessary to place him under restraint. We trust after a few days' rest and absence from excitement the Professor will be restored to some degree of sanity.”

Tolmaque’s behaviour (2) had also involved uninvited visits to the police station, where he became such a nuisance that he was sent away, but he was abusive and threatening, and ended up being locked in a cell, later to be taken to the hospital where he refused all attention and walked out, but was again locked up in the police cells. It was noted that the General Hospital had no provision for treatment of such cases, nor any power to detain a person; neither had the gaol any provision for dealing with afflicted people. On March 29, Dr. Thompson told a court that Tolmaque’s mind was ‘decidedly unhinged’, but that it might be only temporary, and suggested admitting him to hospital for a time; but Martin refused strenuously, addressing the Bench in great excitement and demanding to know on what evidence he was considered ‘insane.’ He became so overwrought that the magistrate ordered his removal from the court, and Martin was remanded for a further week.

In an indictment of the support systems available at the time, Tolmaque was discharged from remand on April 4. The court report of his appearance on the 4th, and his subsequent disorderly conduct (which led yet again to his arrest just days later) makes it abundantly clear that he was in no fit state to be released without support:

(3) “Professor Tolmaque.— This professor of magic and various other things was finally brought before the Bench 4th instant and discharged. Mr. Hudson, who was on the Bench, asked the professor what was the cause of his peculiar behaviour, whereupon he made a most wonderful statement. He said that he had constituted himself a private detective, in order to see whether publicans would serve him after hours, as readily as they would men who were under the influence of liquor. To fully test this point he had always acted as if he himself were intoxicated; and with one or two exceptions he had always been able to obtain admission, and at the front doors. Turning to the reporters' box, the professor said “You don’t seem very anxious to report this matter?” but this was a great mistake on the part of the professor. He seemed very sore about Mr. Murray having remanded him, and continually alluded to him as “the gentleman with the blue spectacles.”

The unfortunate man's mind certainly seemed to be very much deranged, and it is to be hoped that his friends will look after him, and see that he is kept out of harm’s way.

The Professor again appeared at the Police Court on Monday, charged with having disturbed the peace on Sunday. Since his discharge last week he behaved in a very eccentric manner. When he left the gaol he had, it is presumed, no money, and how he has lived since is a mystery. On Saturday afternoon he accosted a gentleman who had kindly offered to help him, and said that the help would be very acceptable now. The gentleman replied that he did not mean to help him in that way but would be glad to raise funds to take him to Melbourne. The Professor then said that a few shillings would do to carry him on till Monday. Five shillings were given, to him by this benevolent gentleman, whereupon the Professor visited the nearest hotel, and in colonial parlance, blew the five shillings. On Sunday he was the centre of attraction in Brisbane-street, stopping people and speaking to them, also dropping his pipe, pouch, and pocket-book on the ground, and asking people to pick them up, saying he was too unwell to stoop. His conduct at last became so disorderly that the police were obliged to interfere, and take him into custody. On Monday Constable Dore, who arrested him, detailed the defendant’s behaviour; saying that he was creating a great disturbance near St. Andrew’s Church by shouting, and when the Salvation Army came along he became more excited, and invited them to dine at Sutton’s Coffee Palace with him. The Magistrate sentenced the unfortunate man to one week’s imprisonment without hard labour, and stated that he would be examined by a doctor. The Professor, on leaving the dock, said “I have been here so often, I think it is almost time I engaged a legal man. Good morning, your Worship!”

Martin was again discharged on April 11 but immediately arrested as he left the gaol. At court he was somewhat less excitable, but criticised Inspector Coulter’s elocution, found fault with the handwriting on his charge papers, quoted Shakespeare and (said the Telegraph) displayed a “cool, critical demeanour … the professor, whether of sound or unsound mind, is a person of infinite variety of views, modes of expression, and resources.”

(1) “Professor Tolmaque Again. — Mr Martin Beaufort Tolmaque was introduced to the notice of the Justices presiding at the Police Court yesterday [April 16]. The bench consisted of Mr James Scott and Mr F. W. Von Steiglitz. The charge indicated misfortune more than fault. The Professor was alleged to be not sane; that he required control, and when liberated was left to wander about uncontrolled. The Professor promptly and indignantly pleaded not guilty to the mild impeachment. He denied that he was a lunatic, and demanded to be released from custody. Mr Coulter put in his own written statement of his extensive experience of Mr Tolmaque's state of mind, and also the statement of Mr. Wm. Miller, under gaoler, as follows : — Martin B. Tolmaque has been under my charge at various intervals since the 24th of March last. His delusion appears to be with regard to his mesmeric power and the influence he has by it on others. He was placed for treatment in the gaol hospital, and there his restless habits at night disturbed the other patients. He thinks there is a conspiracy on the part of the police and magistracy to injure him, and that his complaints are un-redressed. I produce a letter which he sent me yesterday. The Gaol, Tuesday, the day after Whit Monday. To Miller, Esquire, from Martin Beaufort Tolmaque, Knight of the Legion of Honor, decorated by his late Majesty the Emperor of the French, Napoleon the third. (Personally in Paris, 1863.) Having reason to doubt that certain information I gave (voluntarily) to Mr Coulter, Inspector of Police in the city of Launceston, Tasmania, yclept Van Diemen's Land, may not be properly attended to, I beg to volunteer to give the aforesaid information on oath before His Worship the Mayor, Fairthorne, Esquire, and would be pleased if you would kindly inform me what steps or means I must employ in order to obtain the desired effect. I am in possession of much similar matter in reference to herein. On Public Service Only.

Mr Coulter also put in the medical certificate of Dr. Thompson, who, after examining Martin Beaufort Tolmaque, a conjuror, stated — “On the 23rd March Tolmaque came to Hospital premises at 3 a.m. Was cautioned not to come there again. He had been pursuing a purposeless vagabondage ever since he was a patient in Hospital previously. He imagines that people conspire against him, threatens violence against his best friends, is afraid of being poisoned. I am informed by others that he carries basaltic metal about with him, and states that it carries gold ; and that he is continually attitudinising in the streets, trying to mesmerise places and persons.”

All these documents were read by Mr Spotswood. The Professor solemnly averred that he had not been examined by Dr. Thompson, and he was prepared to make oath he had not seen Dr. Thompson for a fortnight. He asked, during the reading of the documents, for a sheet of paper to enable him to make notes of the proceedings. The notes were hieroglyphic. He said they were taken in that way so that others should not understand them. Mr Coulter submitted an order or warrant for the signature of the justices. This stated that having called to their assistance Dr. Thompson, and being satisfied from his certificate that Mr Tolmaque was a person of unsound mind, not under proper care or control, and requiring care and medical treatment, they directed that he be received as a patient in the hospital for the insane. Mr. Steiglitz objected that the bench had not had the assistance of Dr. Thompson. They required the doctor to appear there and make his statement before them. For this purpose they would remand Mr Tolmaque until next day. But Mr Tolmaque objected to this. He said he had been remanded on Monday until 11 o'clock that day. He was there, and he demanded his liberty in the name of the Queen of England. The magistrates said they could not do that; they must remand him for a day. Mr Tolmaque— “But you can give me my liberty on bail!” Mr Steiglitz— “Yes, if you can get persons to bail you. Mr Coulter, what bail will be requisite?” Mr Coulter - “Any two respectable persons who may be willing to take charge of him and keep him under proper control. It is not necessary to name any amount as surety. Mr Steiglitz— “You can have bail on the condition mentioned by Mr. Coulter.” The Professor— “Thank you, gentlemen. I have been more courteously treated by your Worships than by any magistrates I have met with on that bench.” The Professor was then taken back to gaol and no benevolent friends undertook to take charge of him. The man is very intelligent, and has much method in his madness, but he is certainly not in a fit state to be at large. He is destitute of means, is indebted to Mr Susman for souvenirs he distributed liberally to the audiences attending his entertainments, and he requires a home, medical treatment, care, and control. He will be supplied with all these at the hospital much better than in gaol.”

The following day (April 17) the doctor who was supposed to have attended court with an examination of Herr Martin did not appear, and the astounding decision was made to once again release him to roam in public. His conduct in court had again been peculiar, making accusations against several people. The result of this discharge should have been entirely predictable. Tolmaque wandered the streets, demented, homeless, and without means of support. He approached the Fire Brigade Hotel at 2a.m. and, being refused admission, started bombarding the hotel windows with road metal, breaking windows until he was chased away and re-arrested to spend the freezing evening in the police lockup.

A letter to the editor of the Launceston Examiner, April 21, queried why the courts seemed unable, despite medical and police representations, to take the decision to send Professor Tolmaque to the New Norfolk Asylum in the south of Tasmania. “The publican is made to suffer by having the slumbers of all his household disturbed, as well as having to make good all damages, for he has no remedy against a penniless lunatic … I think that there are sufficient grounds for an action against the said two magistrates for setting at large a lunatic …”

Tolmaque, once again before the bench, denied all charges, refused to sit down, and would not accept being tried. He was again remanded to appear six days later.

It should not be thought that the people of Launceston were without sympathy for Martin; the Examiner published a letter on April 23:- “…there can be no doubt the poor deluded Tolmaque is not a fit subject to be roaming, homeless, friendless, and penniless, about our streets, refused shelter and lodging these bitterly cold nights by all except the police, who … appear to have dogged and watched this man from the time he left gaol, and then immediately an opportunity offers have marched him back in triumph. I ask is this treatment calculated to restore a sick man’s health, or improve the malady of a disordered mind? Is it not rather the way to increase the disease?” and a subscription list was suggested to receive donations in assistance of the unhappy magician.

Finally, on April 25, another court hearing was held, with more verbose argument from the magician. For the first time, the court report (4) mentioned that Tolmaque “was treated in the Hospital for some weeks and was in a depressed state of health, and on one occasion said he would commit suicide but for the fact that his heart failed him; his health mended and he was discharged from the Hospital. He followed his calling of conjuring for some days in the town and country; on March 23rd Tolmaque again presented himself at the Hospital…”

So Tolmaque had spent some of his missing days in Tasmania (presumably around February) in hospital, only to rally and take himself off to perform his magic show at different places, including the highly-praised Easter Fair shows, with no apparent aberration, before once again sinking into despair. It has to be wondered whether some of the periods in previous years, when he had vanished from view, might have been due to the same cause, and that he was either suffering depression or receiving hospital treatment long before his Tasmanian collapse.

At the end of this court hearing, the Police Magistrate finally issued their order, and Martin Tolmaque was removed to the New Norfolk Hospital for the Insane.

Martin Tolmaque’s Illness

It would be presumptuous to attempt a medical diagnosis of Herr Tolmaque’s condition as presented during early 1884. There are, however, some observations that might be made by looking at the sweep of his whole life. Tolmaque, from his earliest years, displayed a restive inability to settle in one place, or one task. He was clearly a person of strong intellect and was not shy about displaying his abilities; the eloquence of his writing was not merely showing off, it demonstrates a genuine ability to see the world around him and to point to its strengths and failings – even his own. Martin had some high-functioning condition which might be viewed today as a form of autism. He also appears, in 1884, to have suffered depression and suicidal thoughts. Yet at the very same time he could step outside of himself and present his magic and phrenology entertainments as though nothing was wrong.

The circumstances in which he lived must also be considered. Some news reports put his problems down to intemperance, but clearly it was beyond that. A man without a home, who immediately spent whatever money came his way, and was effectively friendless in the world where he wandered from place to place, having no social or medical support worth mentioning, must have been at times hungry, frightened and isolated. Whatever mental condition he might have suffered, it can only have been worsened by society’s inability to give him care.

There seems no question that Martin had severe recurring bouts of mental instability (lumped, in 1884, into the general category of ‘insanity’), and that his incarceration at New Norfolk was intended to give him some chance to recuperate. At the same time, he was not suffering a linear cognitive decline; his writing and performing post-1884 makes it clear that he had lengthy periods of lucidity, retained much of his memory, and was not always suffering from delusions of persecution. Of the many forms of dementia, the most common (Alzheimer’s disease) does not immediately fit Tolmaque’s symptoms, but as the years went on his afflictions continued, and the question must remain as to whether his mental decline was due to reasons of incurable physical deterioration, or whether modern-day psychiatric treatment and care might have eased his burden.

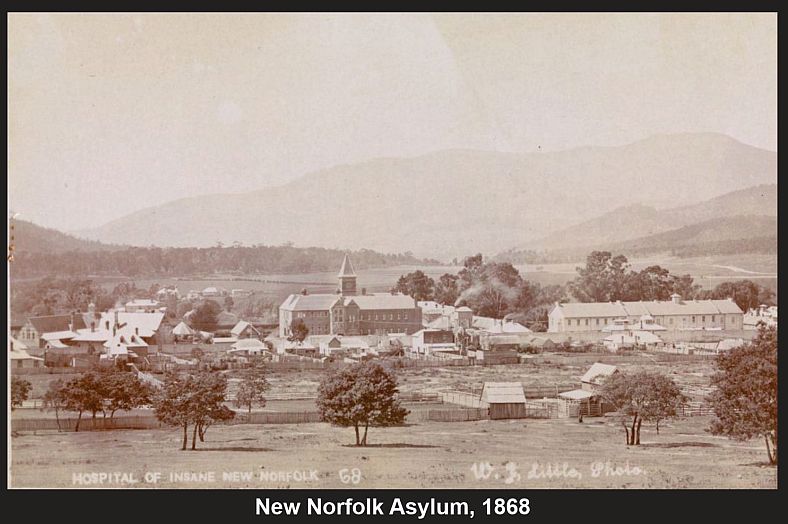

New Norfolk Hospital for the Insane

“… such a system is calculated to make sane men mad, instead of demented men sane.” - Tasmanian News, January 10, 1855The New Norfolk Hospital for the Insane, known also as the New Norfolk Lunatic Asylum, the Royal Derwent Hospital, and Willow Court, had a history running from its construction in the 1820s until its closure in the year 2000. It was situated around twenty miles from Hobart in the south of Tasmania. Originally built as the Convict Invalid Barracks, it progressively came to house those categorised as ‘insane’, and by the end of the 1800s was holding an average of four hundred inmates.

Acknowledging the comparative lack of modern knowledge about medical/physical causes of mental illness, or the treatment of psychiatric conditions, the history of asylums and invalid hospitals (not just New Norfolk) is a confronting and difficult subject. The scope of the medical, social, cultural and political conditions which surrounded the operation of New Norfolk is beyond this book, and the reader is referred to a list of research resources at Reference (6) which form an extensive commentary on the topic.

The New Norfolk hospital was not alone in its methods of operation, or in being criticised for its many shortcomings. It cannot be said that there was a studied cruelty or neglect, but clearly as a place of supposed care and treatment, New Norfolk was severely lacking. Some of its problems came, no doubt, from poor staffing, lack of medical knowledge and underfunding. Political investigations were slow, unwilling to face or remedy root causes of failings, and were beset by the usual self-serving politics which resulted in much sound and fury, but not enough action.

Institutions such as New Norfolk had grown from the mentality of the convict era; illness, poverty and what was seen as social malingering, might best be dealt with by rigid discipline and enforced work on menial and useless tasks. Mental illness was treated by the supposition that quietness and structured routine might bring a person back to a settled frame of mind.

A major fault of the system, and one which formed the central part of Tolmaque’s later complaint, was that there was no categorisation of patients. Residents might be either involuntary admissions, or in some cases, paid residents whose families were simply unable to cope. The gently senile, aged and young, the delusional and the violent were all mixed in together, such that life in the hospital could be as dangerous and traumatising as the problems which had caused their admission – and the violence could come just as easily from the warders, as from the patients.

There were, over the years, a number of Select Committees and Royal Commissions into both New Norfolk and other charitable institutions.

In the year before Tolmaque was sent to New Norfolk, a Select Committee Report to the Tasmanian Legislative Council (September 1883), remarked:-

“… with some few exceptions, humanity, kindness, and consideration for the helpless insane have not found place, and that knowledge, even of the most elementary character, applicable to the treatment of the demented, has not been possessed by the majority of those whose care and supervision the State has entrusted their keeping… it appears to the Committee that the want of skilled training in, and practical knowledge of insanity, under the various aspects in which it presents itself, as exhibited in the person of the Superintendent, is the great cause of the present condition of things met with at New Norfolk … added to which the perfunctory manner in which the Commissioners have performed the duties they have voluntarily undertaken … Keepers and Nurses have not been supplied with either written or printed rules for their guidance, such having been left in his or her department to manage the patients as they thought fit without let or hindrance … D. Harvey - this man has been 6 years in the Asylum. Has been for five or six years in present condition. Has not ever, as far as the Committee could ascertain, shown any symptoms of a maniacal or insane character, beyond a harmless hallucination that in 1863 he saw in the road two tigers, and that he believes they are there still. He performs the whole, or nearly so, of the carpenter's work of the Establishment. This man ought long since to have been discharged. No Commission has sat upon his case.”

The Tasmanian News had reported for some years on the topic of New Norfolk’s management, and on December 17, 1883, had written, “Humanity calls for immediate action being taken; for very serious allegations are made as to the treatment which the patients receive at the hands of the attendants.”

The Treatment of the Insane - Nine Months in a Lunatic Asylum

Martin Tolmaque was committed to the hospital at the end of April 1884, and not discharged until the start of January 1885; perhaps closer to eight months than nine. Despite his assertion that he had gone there ‘undercover’ to report on the institution, there can be little doubt that he did require supervision and care. To some degree, he must have benefitted from the simple provision of shelter and food; but whether this outweighed the chaotic, sometimes violent, and poorly supervised environment in which he found himself, is doubtful.

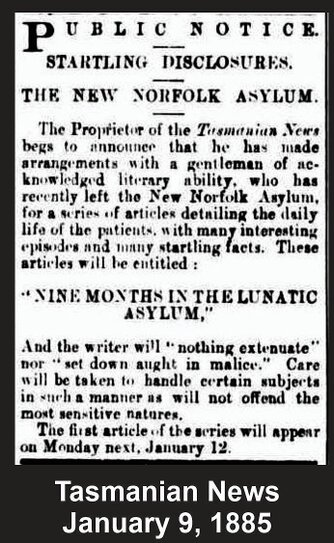

Upon his release, Tolmaque wrote a blistering series of articles, ten in all, for the Tasmanian News. Commencing on January 12, 1885, the series ran until January 24 under the title “The Treatment of the Insane – Nine Months in the Lunatic Asylum”.

As a prelude to his articles, the Tasmanian News blasted the sorry state of affairs in a lengthy article on January 10:

“... It is astonishing how powerful in Tasmania must be the leverage to remove abuses, and how constantly and resolutely it must be employed before success can be hoped for. Especially is this the case with respect to institutions managed by nominee boards. The gentlemen who compose them attend meetings when it suits them, read the officer’s monthly or weekly report as the case may be, ask a few usual questions, give a cursory glance round, and if nothing comes within the orbit of their vision of a prominently objectionable nature, they pass out and go back to their homes or their counting houses in the full belief that they have done the State some service. They have, as a rule, a perfect trust in the officials, and they are loth to believe any disparaging reports they may hear outside, because such reports do not agree with their estimate of the skill, the zeal, or the energy of the members of the staff. The Government pay no attention to rumors or outside reports, because they trust implicitly the Board, the members of which are the proteges or friends of Ministers, and thus evils grow and abuses become permanent…. The experts came to the Colony early last year, and as our readers will member, they condemned the management, the treatment of patients (i.e., the non-examination and non-classification), the practice of herding 80 lunatics together in the back yard, the buildings and site, and chose another locality which they recommended that an asylum should be built. None of the recommendations they made have been acted upon…. for the past 18 months the lives of 285 patients have depended upon the proper dispensing of drugs by a man utterly ignorant of such work. We again repeat that such charge are of too serious a character to be shelved until another session of Parliament can be held.”

Martin Tolmaque’s articles, reproduced in full later in this book, should be read in his own words to appreciate a true insider’s view of the New Norfolk hospital, so his commentary will not be summarised here. However, in a thesis written in 2003, Andrew Kenneth Shaw Piper (5) reveals that Tolmaque also gave some testimony to an enquiry by the President Commissioners (January 1885) which is not included in his newspaper stories, probably since the allegation was too outrageous for public consumption:

“Based upon contemporary reports from the New Norfolk Hospital for the Insane, it can be assumed that male inmates indulged in 'unnatural vice' and that physical coercion and male rape took place. In evidence presented to an inquiry into homosexuality at New Norfolk, sparked by a report in The Tasmanian News of 6 January 1885 which drew attention to “the prevalence of crime of a most serious character among the male patients in the Hospital for the Insane.” Martin Beaufort Tolmaque gave graphic accounts of homosexuality between the male inmates. The commentary of Tolmaque, an ex-patient of the asylum, is plausible and while Macfarlane, the Medical Superintendent of New Norfolk, did not accept it as truthful, there was sufficient testimony in common to believe that Tolmaque's evidence was reflective of events which actually transpired. Further, there is no reason to believe that New Town differed in any way from the picture presented of homosexuality at New Norfolk.

Tolmaque stated that he had “seen men at night in the wards naked, sitting by the side of the beds, behaving indecently by touching each others’ person.” He gave an account of one William Long who employed violence against other inmates to procure sexual favours. He also gave compelling evidence of a series of instances he witnessed in which a number of patients, including one named Shaw, were forced by Long to commit 'indecent offences … if not the capital crime … every night for a period of at least two months'. These were forced acts resulting from the exercise of, or threat of, violence. Tolmaque stated that: “Long employed violence towards Shaw and other patients, pulling them out of bed and knocking them about the head and body with broom handles and heavy boots.” He also described how he had been indecently assaulted himself, on three occasions, by a Warder named Vogel.

In regard to the first such incident he stated: “I was in my bed and had been directed to have mercurial ointment rubbed on the pubes as I was suffering from crabs and the warder Vogel brought the ointment to rub in. In doing so he rubbed his thigh against me and I felt his person pressing against me & he continued to move it against me. I desired him to cease & said I could rub the ointment in myself. He persisted in rubbing the ointment in after I spoke to him in a very rough manner.”

From the evidence that Macfarlane gave to the inquiry, it is clear that Tolmaque had repetitively made allegations of sexual misconduct in the wards but that Macfarlane had preferred to turn a blind eye to them. It was only following the disclosure of such unnatural crime in The Tasmanian News that Macfarlane, and indeed the government, were forced to confront this issue.” [A. K. S. Piper]

This testimony apparently led to some six or eight inmates being removed by the end of January from New Norfolk and placed at the Cascades Asylum at South Hobart. Tolmaque was mentioned several times in parliamentary proceedings and reports up to 1888.

Whatever may have been his state of health upon his release, the eloquence of his stories, and his restrained fury, show that Martin was capable of clear thought and detailed memory. He was almost refused release from the hospital because those in charge feared he might make complaint: “A great deal more talk of a similar nature passed between us, and then at last they yielded, and consented to let me go on the condition of my not making any complaints. I have kept, and I mean to keep, my word in this respect. I shall make no complaints, commission no actions, seek no redress, either public or private, and unless forced, bear no evidence against the place. … Against writing for the press I did not for swear to the commissioners.” [Tolmaque, The Treatment of the Insane, No.10]

The Daily Telegraph (January 12) went so far as to issue a precautionary statement, giving political cover to the Asylum and its operators – “It is as well that it should be known that when before the Commissioners on Tuesday last he expressed himself as well satisfied with his treatment whilst he had been a patient, and had no complaint to make against the medical gentlemen in charge, or other officers of the institution, and seemed grateful for what had been done for him.” This statement needs to be weighed against Tolmaque’s version of his release, in Chapter 10 of his articles.

Martin gave his own summary of his nine months at New Norfolk, at the end of his series:

1. At New Norfolk the patients are not all insane, and a great many of the old hands never were and never will be insane.

2. At New Norfolk you do not classify your patients.

3. At New Norfolk you don't know how to classify your patients.

4. At New Norfolk you seem perfectly callous and indifferent to those considerations.

5. At New Norfolk "might is right," as it was in the Middle Ages.

6. At New Norfolk you govern by stratagem, equivoque, and frequently by force.

7. At New Norfolk you seem to know nothing about treating your afflicted, suffering charges with kindness and consideration.

8. At New Norfolk your system is, by far, worse than the old one so ably exposed by Thackeray in his ‘Vanity Fair.’

9. At New Norfolk, you torture people as though by right Divine.

10. At New Norfolk you will sooner or later have to give an account of your doings.

The Queenslander (Brisbane) February 14, 1885 from our Hobart correspondent:-

“The New Norfolk Lunatic Asylum has been brought into considerable prominence during the past month. It may be remembered that some time since, in consequence of popular agitation, Drs. Manning, Dick, and Patterson were requested to visit the asylum, to report upon the management, the locality, and other matters that had been brought into public notice. They accordingly visited the institution, and reported somewhat unfavourably upon the management, and wholly condemned the site. Various improvements were suggested, and it was recommended that a piece of land be procured on the Derwent, in the vicinity of Glenorchy. The medical gentlemen returned to their homes, and nothing was done.

The fact is that the commissioners who manage the affairs of the asylum are a pleasant lot of gentlemen, who meet periodically, have a chat with the superintendent, walk over the asylum, sit down to a cozy lunch, and get into that mellow state of feeling which altogether indisposes them for the invidious task of finding fault. And they are socially mixed up with individuals in high office, so that it may easily be accounted for that the Ministry were extremely reluctant to make any changes.

However, rumours have been afloat of a most serious nature, rumours of criminal practices on the part of patients and of brutal treatment on the part of wardsmen. In consequence of this a deputation, consisting of ministers of religion and other residents of Hobart, waited upon the Premier, urging him to take steps to carry into effect the proposed alterations. The Premier seemed disposed to treat the deputation rather cavalierly. A Royal Commission, he said, had already reported on some of the matters. The question of site would shortly be laid before Parliament. He told one of the gentlemen present, with singular logic, that if he questioned the statements of the commissioners he did not see what use it was his coming there. But even Premiers have occasionally to bow before public opinion. The ugly rumours above mentioned have been confirmed. Five of the patients have been proved to be addicted to abominable vices, and others are suspected.

The Evening News, a paper which was started a few months since, and has attained a considerable circulation and influence, has published a series of articles, by one Professor Tolmaque, a mesmerist, or something of that sort, who has been nine months in the asylum. This individual gives out that he was there like the ‘Amateur Casual,’ to observe and to describe; if so, he certainly got more than he bargained for. The plain truth, probably, is that he was suffering from a temporary mental aberration, brought on by intemperance. He seems sane enough now, and has made some serious revelations. While speaking without any marked degree of censure of the part of the building which, being in front, is more exposed to public inspection, where the milder cases and the more respectable patients are, he paints the ‘backyard,’ as it is termed, in hues almost as dark as those in which Dante depicted the ‘Inferno.’ In this part of the asylum there are eighty patients, some of them of the worst type, without proper classification, without effective supervision, with attendants of the lowest class, and possessing the most brutal and depraved tastes. The weekly bath appears to be an occasion of wild disorder and rough horseplay, during which cries of pain and terror may be heard from the weaker victims, and coarse and obscene jests from the wardsmen. Then there is a scramble for clothes - in one place a man of large proportions vainly struggling to get into a ragged flannel vest that might fit a diminutive boy, and another unable to get a vest at all, but compelled to shiver in a coarse and flimsy cotton shirt, or to seize, as the professor did, a blanket from one of the beds to wrap around his person. One of the inmates has developed a taste for kicking the others in the most sensitive parts of the frame when a chance occurs, which is not seldom. An attendant is charged by Tolmaque with having violently robbed him of rings he wore on his hand. Exasperated and wretched, he once asked the superintendent if he might write a letter, and was answered significantly that he might if it were of the right sort. A fresh committee of inquiry has been appointed to inquire into the various matters that have been brought before the public. The general belief is that the only effectual remedy will be to remove the institution altogether from New Norfolk, and to place it under the management of an entirely fresh set of men. The site recommended by Dr. Manning and the others would be highly suitable if there were an adequate water supply, which there is not. However, as it is suitable in other respects, that difficulty might be overcome, though at some expense.”

References for Chapter Seven

(1) Daily Telegraph, Launceston, April 17, 1884.

(2) Launceston Examiner, March 25, 1884.

(3) The Tasmanian, April 12, 1884.

(4) Launceston Examiner, April 26, 1884.

(5) Andrew Kenneth Shaw Piper, AKS 2003 , 'Beyond the Convict System: the Aged Poor and Institutionalisation in Colonial Tasmania', PhD thesis, University of Tasmania. The documents he quotes in regard to Tolmaque’s accusations have not been sighted by this author but their authenticity is not in question:

- Archives Office of Tasmania: CSD 13/81/1662, Dobbs to President Commissioners of the New Norfolk Hospital for the Insane, 7.1.1885

- Archives Office of Tasmania CSD 13/81/1662, Evidence presented at Inquiry by Martin Beaufort Tolmaque.

(6) Of the extensive documentation regarding New Norfolk, these sources relate to Tolmaque and the period surrounding his first committal.

‘Incoherent and Violent if Crossed’: The Admission of Older People to the New Norfolk Lunatic Asylum in the Nineteenth Century.Author: Anthea Vreugdenhil

Source: Health and History , Vol. 14, No. 2 (2012), pp. 91-111

Published by: Australian and New Zealand Society of the History of Medicine, Inc - https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5401/healthhist.14.2.0091

December 19, 1883 – Tasmania Legislative Council – Session II – Hospital for the Insane, New Norfolk – Correspondence and other papers

December 19, 1883 – Tasmania Legislative Council – Session II – Hospital for the Insane, New Norfolk - Report of Select Committee (No.12)

November 19, 1885 – Parliament of Tasmania – Administration of Charitable Grants – Report from the Select Committee (No. 154)

1886 – Parliament of Tasmania – Hospital for Insane, New Norfolk – Interim Report of Official Visitors (No.48)

1888 – Parliament of Tasmania – Hospital for the Insane, New Norfolk, Report for 1887 (No.9)

1888 – Parliament of Tasmania – Royal Commission on Charitable Institutions (No.50)